Journey to Brazil: Searching for an Answer to a Botanical Problem in Espiríto Santo

Posted in Travelogue on December 12, 2013 by Scott Mori

Scott A. Mori is the Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany at the The New York Botanical Garden, and his primary research interests are the ecology, classification, and conservation of tropical rain forest trees. His most recent book is Tropical Plant Collecting: From the Field to the Internet. This is the second in a three-part series documenting his latest trip to Brazil.

During two weeks in November, three colleagues and I explored the remnant woodlands of the once-abundant Atlantic coastal forest of Espírito Santo, a Brazilian state on the Atlantic coast just north of Rio de Janeiro. We were searching for poorly known species of the Brazil nut family, whose scientific name is Lecythidaceae, and we were especially interested in collecting in Espírito Santo because it is an area of intensive human development. Only a fraction of the natural habitat remains.

The trip followed my visit to the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden, where I taught a short course on the Brazil nut family. Joining me were Michel Ribeiro, who is preparing a treatment of the Brazil nut family as part of his master’s degree requirements; Anderson Alves-Araújo, a botany professor at the Federal University of Espiríto Santo who is one of Michel’s advisors; and Nate Smith, a specialist in the Brazil family and an Honorary Research Associate at The New York Botanical Garden.

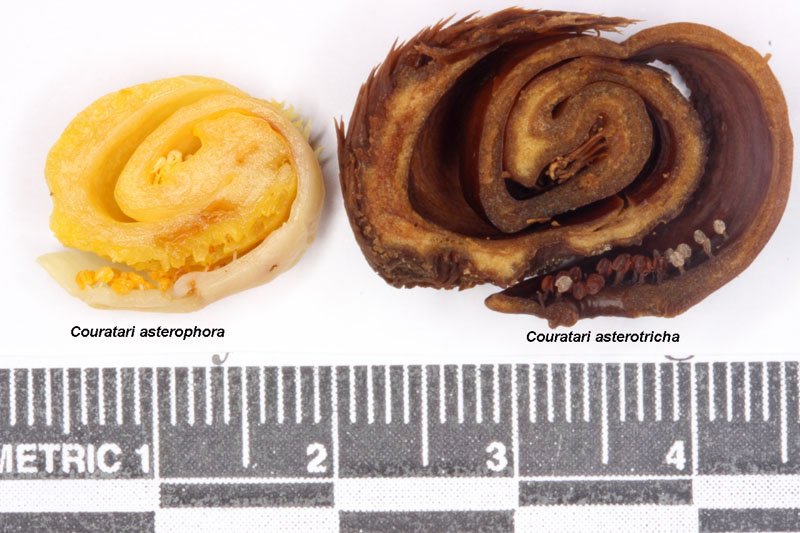

We started by studying collections at four herbaria, one in Rio de Janeiro and three in northern Espírito Santo. We identified specimens, dissected flowers, and examined fruits and seeds to gather data that Michel can use in writing scientific descriptions of Brazil nut species. There are only 12 known Lecythidaceae species in Espírito Santo, and most of them are well-known. However, species of the Brazil-nut genus Couratari still present classification problems, which are most easily resolved by studying trees in their native habitats.

And so our next step was to travel to three biological reserves (Córrego do Veado, Córrego Grande, and Sooretama) in the northern part of the state to see the trees for ourselves. Michel had gotten government permission to collect specimens, but because species in the Brazil nut family are often large trees, Michel sometimes had to climb the trees and use a clipper pole to cut branches bearing flowers or fruits.

In all, we made 42 collections of four genera and 12 species of Lecythidaceae. We were especially fortunate to gather specimens of four different species of Couratari, including many with flowers and fruit. That allowed us to find previously unknown differences in the flowers of these species. In addition, we came to the realization that collections that were previously identified as the Amazonian Couratari macrosperma may, in fact, not be that species. Michel will now write descriptions of the species of Couratari from eastern Brazil and study Amazonian collections of Couratari macrosperma to find out if there is support for our hypothesis that the eastern Brazilian population represents a different species from its Amazonian relatives.

This trip reaffirmed our belief that an understanding of the classification, evolution, ecology, and conservation of tropical plants depends upon the study of herbarium specimens combined with the collection and examination of living plants in the field. The data we gathered will help us advance one of the primary missions of Botanical Garden scientists: providing information to conservation biologists and governmental agencies so they understand what species grow where.

With this information, biological reserves can be established in places where they will protect the greatest plant and animal diversity. Not knowing what to protect might mean that species could be driven to extinction before they are even known. To see what we have already learned about the species of Lecythidaceae in this area, visit our Web site, Conservation Status of the Lecythidaceae of Eastern Brazil.

Next week, I will consider the conservation of plant diversity along the eastern coast of Brazil based on what I saw on this expedition.

Support for our expedition was provided by the School of Tropical Botany of the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden and the Mohammed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund.