The Great Tree Search

Melissa Finley is the Thain Curator of Woody Plants at The New York Botanical Garden.

Figure 1: An aerial view of the Ross Conifer Arboretum

I have recently been tasked with the honor of serving on the committee to select the Great Trees of New York City. In 1985, the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation invited citizens across the five boroughs to nominate trees of unusual size, interesting or rare species, unusual form, and/or historical significance. The great trees of New York provide shade for our playing children, habitat for our birds, and embody the deep cultural and ecological connections between people and nature. Now, after over 35 years, it’s time to create a new list of Great Trees to be featured in an interactive city-wide map, representing the incredible diversity and scale of New York City’s urban forest. Of the original 120 Great Trees designated in 1985, only 65 remain. As time has passed, new trees have grown to impressive sizes, new events have commemorated neighborhood trees, and new gardens have sprung up across the boroughs. It’s time for a new search!

While The New York Botanical Garden represents just a small part of the city, both geographically (250 acres of 192,300 total acres) and as a small subset of the city’s trees (there are approximately 30,000 trees at NYBG compared to an estimated 875,480 NYC street trees!), our venerable garden features many notable trees which deserve consideration in the Great Tree Search. As the Thain Curator of Woody Plants here at NYBG, I would like to share a few recommendations of my personal favorite trees and invite all the visitors and admirers of our tree collections to nominate at least one tree for this project.

Through a public process, New Yorkers in every community are now invited to nominate exceptional trees, as defined by their historic, botanical, and cultural significance, with the goal of increasing both the number of trees deemed ‘Great’ and the diversity of people telling these stories. The nominations are open through the end of 2023. Here are the criteria provided by NYC Parks for selecting your favorite great tree:

- Historic Significance: Trees bear witness to many important historical moments across our city. We are prioritizing nominations that reflect the diversity and lived experiences of New Yorkers. An example of a historic tree is a tree that may represent an important movement, protest, or era of historic change in the community.

- Botanical Significance: Some trees may be rarer, larger, or unique in other aesthetic or scientific ways. We will consider rare species or varieties, remnants of historic or native ecosystems, trees with profound form or structure (such as weeping, upright, or other unusual shapes), and the location of the tree in the immediate landscape, among other features. Examples could include trees such as the Alley Pond Giant, which is believed to be the tallest tree and oldest living organism in NYC.

- Cultural Significance: Some trees may have a strong association with a belief, person, place, or event of cultural importance to a community. We welcome nominations that reflect cultural expressions, or stories from historically marginalized communities. Examples include trees mentioned in a beloved book, song, or that appear in visual art.

The prospect of having to choose a short list of trees for this article, from the hundreds of trees that I hold dear at this garden, is daunting to say the least. As a life-long tree lover (read: tree nerd) and someone who spends every weekday here at NYBG, it’s very difficult to narrow down to a short list, much less a singular favorite tree. Every tree is unique and interesting in its own way. I’ve decided it would be best to use some of the language provided by NYC Parks to create a handful of categories—then suggest an NYBG tree for nomination in each category. Those categories are: great size, botanical significance, unusual form, historic significance, and cultural significance.

1. Great Size

Tree size can be measured in a variety of ways. Typically, one considers either just the height, just the diameter, or the total volume of wood. I’ll be the first to admit that math is not my strong suit, and the prospect of attempting to calculate the total volume of a large tree is, I assume, well above my level of understanding of calculus, so we’ll leave that one to the pros. The other two categories, height and diameter, are much easier to determine, and allow me to sneak a sixth tree into my list of favorites.

Figure 2: NYBG’s uncommonly large London plane, which is the most common street tree in New York City

Tree diameter is measured at 4.5 feet, or what is called breast height, since it is approximately chest high for a male of average height (why we use this chauvinist standard to this day is perhaps an article for another time). This has been an American measurement standard since the early days of American silviculture and arboriculture. The largest single-stem planted* tree diameter at The New York Botanical Garden is a London plane tree (Platanus × acerifolia) located near the Mosholu Gate entrance. The tree measures 59.1 inches across! With its eye-catching and hefty limbs stretching horizontally out from its wide, sturdy trunk, it is a showstopper of a tree. This species is an urban forestry favorite and one of the most common street trees in NYC. They can easily be identified by their thin, exfoliating bark in shades of tan, brown, and olive.

*There are some larger diameter trees around the grounds, all of which are native and grew spontaneously on the site before the Garden was established. This London plane is the largest of our planted trees. Although it is neither the tallest nor the thickest at breast height, its sculptural quality and sheer mass make it nomination-worthy.

Tree height, on the other hand, is calculated by using a little geometry. First, visualize a triangle that is formed by three points: 1) where the measurer is standing, 2) the base of the tree, and 3) the very top of the tree. You can calculate the missing side of the triangle, the height of the tree, by measuring the other two sides: the distance from you to the bottom of the tree and the distance from you to the top of the tree. The distance to the top of the tree can be found by using a laser measuring tool or clinometer.

Figure 3: The mature trees of the Maureen K. Chilton Azalea Garden

The tallest tree in the garden is hidden away deep in the Maureen K. Chilton Azalea Garden, amongst what we call The Cathedral: a stand of towering giants that predate NYBG itself and form a dazzling canopy of dappled light and shadow. At 160 feet tall, this tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera) is a native goliath. Unfortunately, its height is a little difficult to comprehend since it is located at the bottom of the hill. But it is well worth the trek to the Azalea Garden overlook, where you can marvel at the size and age of this tree and its wizened companions.

2. Botanical Significance

The white ash or American ash (Fraxinus americana) is native to the eastern and central United States, where it was once abundant in hardwood forests, standing tall next to red maples, sugar maples, hickories, and oaks. Interestingly, ash trees are a vital food source for frog tadpoles due to the low concentration of tannins—a bitter compound—in the leaves. The tadpoles feed on the leaves as they fall into ponds and lakes. Of course, ash is also famously an excellent finished wood, frequently used for baseball bats, tool handles, furniture, and flooring due to its hardness, density, and straight grain. I’m including this tree on my list as botanically significant because, unfortunately, it has become somewhat of a botanical rarity in the US, and especially in the Northeast, due to the impacts of an invasive insect called the Emerald Ash Borer, commonly known as EAB. This small green beetle native to East Asia has devastated the North American ash population, killing an estimated 50 million trees to date and spreading across the country. Emerald ash borer lays its eggs in the bark furrows of an ash tree, where the larvae will hatch and burrow beneath the bark, forming galleries of larval tunnels which can damage the vascular tissues of the tree, preventing water and nutrients from reaching the canopy. After 1–2 years the adult beetle emerges to seek food and mates, and the host tree may eventually die. For more information about the emerald ash borer, visit here and here.

Figure 4: NYBG’s largest white ash has escaped the ravages of emerald ash borer so far.

Fortunately, emerald ash borer can be managed through the responsible use of pesticides and extensive monitoring. At NYBG, we’ve been able to protect our high value ash trees from EAB so far. My favorite white ash tree at the garden is a monstrous old tree growing along Conservatory Drive, just down the way from the Hudson Garden Grill and near the perimeter gate. This magnificent specimen measures 47” in diameter and towers to at least 100’ tall. I believe this is the largest ash I’ve ever seen, and it is certainly a rare and impressive specimen now that the entire ash population has been so devastated. This tree is a profound remnant of what New York hardwood forests used to be.

3. Unusual Form

The Tanyosho Pine Grove is comprised of a grove of Japanese red pines (Pinus densiflora) that were selected for an unusual umbrella-like branching form, fittingly called ‘Umbraculifera’. This rare cultivar was developed centuries ago in Japan, where it is called tanyosho or utsukushimatsu. These very slow-growing trees are characterized by the eye-catching cinnamon-red exfoliating bark of its many, similarly-sized stems which sweep up into spreading, flat-topped and umbrella-like boughs after many years. It was first recorded into botanical literature in 1890 by German author and botanist Heinrich Mayr.

Figure 5: The 1908 grove of Tanyosho pines

The historic grove of Tanyosho pines at NYBG was planted in 1908 as part of the oldest existing collection at the garden, the Pinetum, now called the Ross Conifer Arboretum. Plantings and planning in the Pinetum and the Fruticetum (which was destroyed during the construction of the Bronx Parkway in the 1930s) began as early as 1898. These plants were a donation from Lowell M. Palmer, an NYBG member and conifer enthusiast, who gave over 400 trees to the garden. It is incredibly rare to find such a healthy and mature stand of these rare pines, especially in the West.

4. Historic Significance

Figure 6: The unusual flower of the dove tree is the cluster of black speckles, backed by a white modified leaf called a bract.

The dove tree, also called the handkerchief tree (Davidia involucrata) is of great historic significance due to its role in the history of botanic gardens. Throughout antiquity and the medieval period, the academic garden was centered around the production and research of medicinal plants, and it was in this context that plants were described and classified. The world’s first botanists were also medical doctors. As Europe entered the early Modern period, termed optimistically the “Age of Discovery” by some, the West’s relationship to plants began to change. As explorers and traders reached new continents they brought back unusual plants, which sparked the development of modern taxonomy, as the differences and similarities between plants from across the world became clearer. These new plants were brought to newly formed arboreta and gardens and arranged in the newly emerging taxonomic system so they could be studied. The work of early plant collectors made these new academic botanical institutions possible.

One of the most famous plant explorers was E.H. Wilson. Ernest Henry Wilson was an Englishman hired initially by the Veitch Nursery, and later the Arnold Arboretum, to bring back rare and unusual plants from east Asia. In 1899, he was hired to plan and execute an expedition to bring back seeds of the Davidia involucrata, or dove tree, first collected in 1869 by the French missionary Père David. The beauty of this tree is best captured by Wilson’s own journal entry in 1900:

“On May 19th, when collecting near the hamlet of Ta-wan, distant some five days southwest of Ichang, I suddenly happened upon a Davidia tree in full flower! It was about fifty feet tall, in outline pyramidal, and its wealth of blossoms was more beautiful than words can portray … Now with a wider knowledge of floral treasures of the Northern Hemisphere, I am convinced that Davidia involucrata is the most interesting and most beautiful of all trees which grow in the north temperate regions. The distinctive beauty of the Davidia is in the two snow-white connate bracts, which subtend the flower proper … The flowers and their attendant bracts are pendulous on fairly long stalks, and when stirred by the slightest breeze they resemble huge butterflies or small doves hovering amongst the trees.”

A mature specimen of the dove tree is located next to the Harding Laboratory here at NYBG, just behind the cherries at the Mosholu Gate. Be sure to make the trek to see this unusual tree in flower in late May. I invite you to think on the arduous trip made by E.H. Wilson to bring this tree back to the West while you make what is hopefully a much easier journey through our garden gates.

6. Cultural Significance

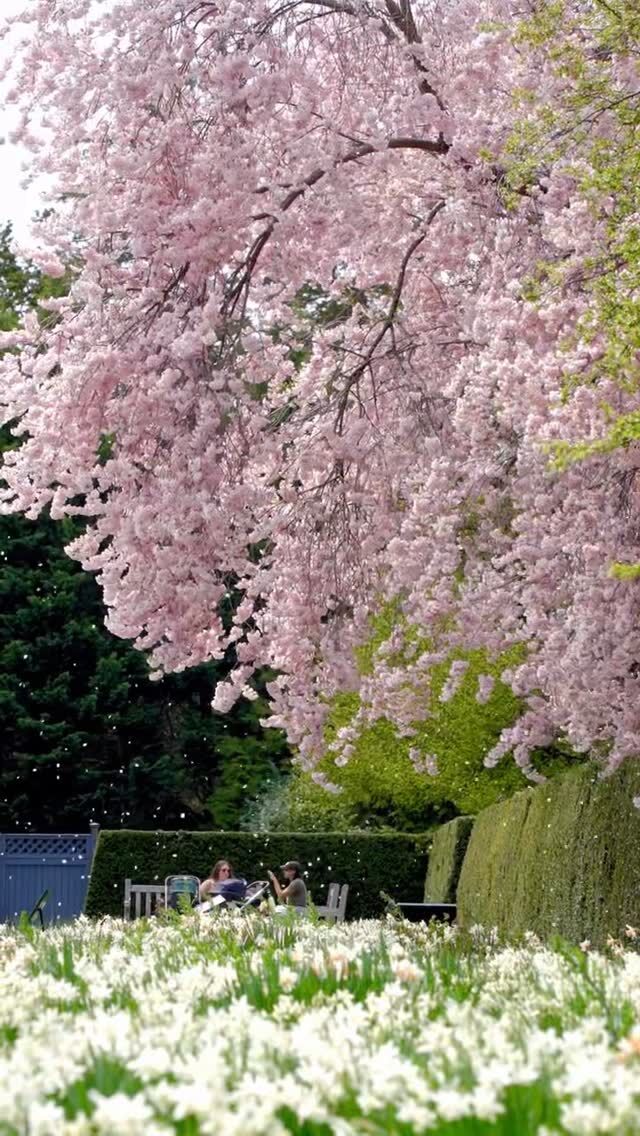

Figure 7: The Mother Tree

Construction of the Museum Building, now called the LuEsther T. Mertz Library, at The New York Botanical Garden began in 1897. The Garden’s planners selected a centrally-located knoll for this grand Beaux Arts building, constructed to house the young Garden’s library, scientific collections, and education programs. Located near the building site was a mature tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera). This ancient tree inspired the planting of two double rows of tulip trees along the drive leading to the impressive new building. Named a New York City landmark in 2009, along with the adjacent Mertz Library and Lilian and Amy Goldman Fountain of Life, the Allée was dedicated in 2021 in honor of John J. Hoffee, a Trustee of the LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust and longtime friend of NYBG.

That pre-existing tulip tree, which we at the garden call the “Mother Tree,” is a powerful symbol of the garden and its historic connection to the land. She is estimated to be over 200 years old, already venerable and sizable at the time of the Garden’s founding. It is difficult to imagine a more culturally significant tree to this institution.

6. Bonus Tree

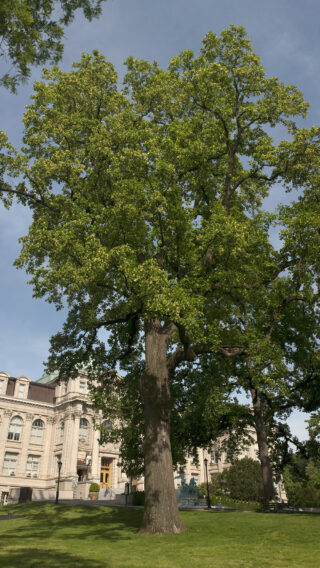

I can’t help but include one more interesting historic tree in our collections. The lacebark pine (Pinus bungeana) in the Ross Conifer Arboretum was received in 1909 from the USDA Bureau of Plant Industry plant introduction program. This program was started in response to high demand for new agricultural and horticultural plants that would be of economic value to the United States. Plants were imported from around the world and distributed to universities, agricultural research centers, botanic gardens and arboreta in order to conduct testing. For new trees species, this meant determining long-term growth characteristics and desirable garden traits that would make for an attractive landscape specimen. The lacebark pine is just one such tree. Named for its luminous grey and green mottled bark, which slowly bleaches to bright white in the sun, this long-lived Asian conifer is a showstopper. In China and Korea, the lacebark pine is traditionally planted near temples and cemeteries, where ancient specimens up to 500 years old or more can be found to this day.

Figure 8: The lacebark pine in the Ross Conifer Arboretum

These are, of course, just a few suggestions out of many, many incredible trees here at The New York Botanical Garden and across our wonderful city. I hope that this list will inspire you to nominate at least one tree for the Great Tree Search, whether it’s a historic tree at the botanical garden or your favorite local street tree. You can use the NYBG Plant Tracker, either on your desktop at home or via your phone while you’re here, to explore our trees and even find a new favorite.

Figure 9: The author pointing out the tallest tree at NYBG

Here’s how you can nominate a Great Tree of NYC:

- Navigate to the NYC Parks Great Tree Search page.

- Fill out the online form with information about the tree. If you are nominating an NYBG tree, just list “New York Botanical Garden” as the Location.

- Attach a photo of the tree. You can even use the photos embedded in this article if you are planning on nominating one of my favorites.

- Submit your nominations by December 31, 2023!

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.