Garden Scientist Leads Healthcare Workshops in Bolivia

Posted in People, Science on August 6 2009, by Plant Talk

Promotes Dialogue between Traditional and Western Medicine Practitioners

|

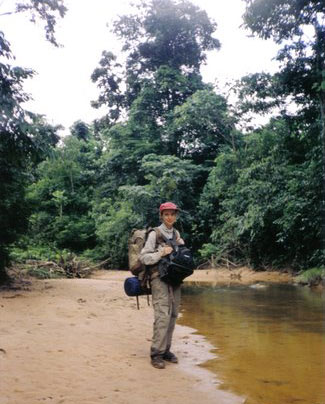

Ina Vandebroek, Ph.D., is a Research Associate and Project Director of Dominican Traditional Medicine for Urban Community Health with the Botanical Garden’s Institute of Economic Botany. She has also conducted research on the medicinal uses of plants for community healthcare in Bolivia since 2000. Photo of Ina by Bert de Leenheer |

Bolivia is a landlocked country in Latin America with a high level of biocultural diversity. The Andean mountains that run through the country from northwest to southeast give rise to 23 distinct ecological zones, ranging from the high plains (altiplano) at 13,123 feet, to lowland Amazon rain forest at less than 1,000 feet. The total number of plant species found in Bolivia is still unknown, but estimates are around 20,000. More than 30 distinct indigenous languages are spoken in the country—a reflection of its high ethnic diversity.

Bolivia is a landlocked country in Latin America with a high level of biocultural diversity. The Andean mountains that run through the country from northwest to southeast give rise to 23 distinct ecological zones, ranging from the high plains (altiplano) at 13,123 feet, to lowland Amazon rain forest at less than 1,000 feet. The total number of plant species found in Bolivia is still unknown, but estimates are around 20,000. More than 30 distinct indigenous languages are spoken in the country—a reflection of its high ethnic diversity.

Ever since I first set foot on Bolivian soil, I became enamored with the country’s cultures and traditions. Bolivia, or la llajta (home) as the Quechua people who make up one-third of its population would say, is where you eat roasted cow heart with peanut sauce (anticuchos), pay a ritual tribute to Mother Earth (la Pachamama) each first Friday of the month, or negotiate a good price with vendors at the largest open-air market in Latin America. The market, called La Cancha in the city of Cochabamba, is where you can find nearly anything you dream of. My favorite corner is where the dry and fresh herbs are as well as seeds, incense, llama fetuses (used for spiritual purposes), and mesas or ritual preparations for Mother Earth.

The Bolivian lowlands are home to several indigenous groups, many of whom do not have easy access to biomedical healthcare. This means that, all too often, traditional medicine is the only healthcare available. The crushing reality is that in life-threatening situations such as a hemophilic newborn, a venomous snakebite, or a serious gallbladder infection—all to which I have been a powerless witness—people die without reaching a hospital. Luckily, for many other illnesses, traditional healers are able to play a secure role in maintaining overall community health. Being indigenous community members themselves, healers’ role in healthcare is pivotal. Patients trust them and share with them the same cultural beliefs about the causes and treatment of illnesses.

Last month I began organizing indigenous community health workshops in Bolivia with the objective of promoting dialogue between biomedical healthcare providers and traditional healers about frequently occurring health problems. The idea is for the two groups to reach consensus about the best ways for traditional healers to deal with these conditions in communities without access to biomedical healthcare.

The workshops take place in Eterazama, a small village close to the rain forest home of the Yurakaré and Trinitario peoples of the Indigenous Territory and National Park Isiboro-Sécure. The biomedical healthcare providers who participate in the workshops are staff from the department of tropical medicine (CUMETROP) of the Bolivian Universidad Mayor de San Simón; the traditional healers are members of Yurakaré and Trinitario communities. Medical students from the Bolivian university are also participating so that they can learn about the cultural aspects of healthcare and acquire culturally competent skills to treat Bolivian patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds. A fourth group of participants are biomedical doctors who staff primary healthcare services dispersed throughout the National Park (but located outside the indigenous communities). These participants constitute a dynamic team that discusses health topics from different perspectives, taking into account scientific information from the biomedical literature as well as cultural aspects of health, an approach called evidence-based integrative medicine.

The first of four planned workshops took place over three days in July and focused on venomous snake and spider bites, scorpion stings, and external and internal parasites. By showing pictures of snakes, a tropical medicine specialist encouraged indigenous participants to divulge local names for snakes and traditional treatments used for snake bites. The healers’ stories showed how closely indigenous perceptions are based on the natural environment and that traditional medicine is a complex system of healing that is based on a long tradition of observation and experimentation. For example, venomous snakes are known to reside in the same underground network of holes as agoutis, large wild rodents. Since snakes and agoutis are observed to live together, it is believed that these rodents are immune to snake bites; consequently, their gallbladder is used as a medicine for the treatment of snake bites. Other measures are also taken to aid in the recovery of the patient, including total rest for up to two weeks, no visits from other people, permanent vigilance by a traditional healer during the first day, no intake of food, and keeping the patient awake during the first 24 hours after the snake bite.

The workshop also devoted a day to plants used locally for treating the selected health conditions. The discussion began with a book I co-authored, Guidebook to the Medicinal Plants Used by the Yurakarés and Trinitarios of the Indigenous Territory and National Park Isiboro-Sécure. One of the healers’ favorite plants was tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L., see photo at left), frequently used to treat insect bites and stings as well as snake bites. Other plant species also came up during discussion, but indigenous community members frequently expressed their concerns that if information about these species is divulged to the world, outsiders may come and use that knowledge to their own benefit, without taking into account the indigenous peoples who are the original “inventors” of that knowledge. This led us into the much debated field of intellectual property rights. No sufficient mechanisms currently exist to adequately protect indigenous knowledge. The New York Botanical Garden’s James S. Miller, Ph.D., Dean of Science, and Michael J. Balick, Ph.D., Vice President for Botanical Science, a few years ago helped develop Botanical Garden Principles on Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit Sharing.

The workshop also devoted a day to plants used locally for treating the selected health conditions. The discussion began with a book I co-authored, Guidebook to the Medicinal Plants Used by the Yurakarés and Trinitarios of the Indigenous Territory and National Park Isiboro-Sécure. One of the healers’ favorite plants was tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L., see photo at left), frequently used to treat insect bites and stings as well as snake bites. Other plant species also came up during discussion, but indigenous community members frequently expressed their concerns that if information about these species is divulged to the world, outsiders may come and use that knowledge to their own benefit, without taking into account the indigenous peoples who are the original “inventors” of that knowledge. This led us into the much debated field of intellectual property rights. No sufficient mechanisms currently exist to adequately protect indigenous knowledge. The New York Botanical Garden’s James S. Miller, Ph.D., Dean of Science, and Michael J. Balick, Ph.D., Vice President for Botanical Science, a few years ago helped develop Botanical Garden Principles on Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit Sharing.

At the same time that indigenous communities are concerned about misappropriation of their knowledge, we are facing the global dilemma of rapid extinction of many vulnerable plant species and traditional knowledge, even before botanists have been able to record those species, which The New York Times recently reported. The topic of intellectual property rights, as well as another set of health conditions (digestive, respiratory, and reproductive health problems), leaves us with ample food for thought for the next three workshops, which will run during August to October.

Please help support the important botanical research, education, and programs such as this that are integral to the mission of The New York Botanical Garden.