Can Fees for Ecosystem Services Save Rain Forests?

Posted in Science on November 4 2010, by Plant Talk

Paying for Benefits Provided by Natural Systems May Help in Conservation

|

Scott A. Mori, Ph.D., Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany, has been studying New World rain forests for The New York Botanical Garden for over 35 years. He has witnessed an unrelenting reduction in the extent of the tropical forests he studies and as a result has become interested in the ecosystem services provided by them. |

|

Li Gao, a biology student at SUNY Binghamton, studied ecosystem services under the supervision of Dr. Mori as an intern at the Garden this past summer. |

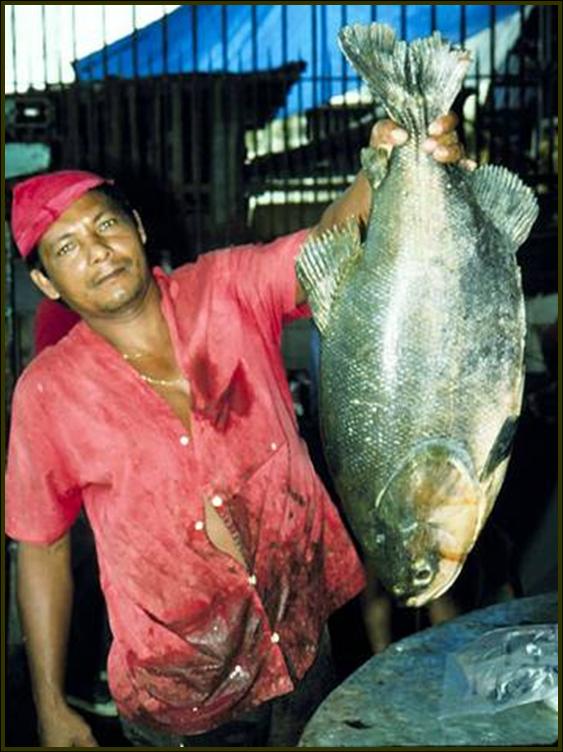

Photo by C. Gracie: Fish harvested from nature is an example of an ecosystem service.

For the past three years, the Institute of Systematic Botany of The New York Botanical Garden has been preparing an inventory of the plants of the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica. Our goal is to document the native plants growing on the Osa through collections and images, most of which are the result of the botanical explorations of Costa Rican botanist Reinaldo Aguilar. The Osa is the last large expanse of lowland rain forest along the Pacific coast of all of Mesoamerica, and is a place where jaguars, large flocks of scarlet macaws, nesting sea turtles, and over 2,000 species of plants (821 of which are trees) can still be seen in their natural habitat.

For the past three years, the Institute of Systematic Botany of The New York Botanical Garden has been preparing an inventory of the plants of the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica. Our goal is to document the native plants growing on the Osa through collections and images, most of which are the result of the botanical explorations of Costa Rican botanist Reinaldo Aguilar. The Osa is the last large expanse of lowland rain forest along the Pacific coast of all of Mesoamerica, and is a place where jaguars, large flocks of scarlet macaws, nesting sea turtles, and over 2,000 species of plants (821 of which are trees) can still be seen in their natural habitat.

Tropical forests boost local economies through the sale of tropical forest products like timber, chocolate, and Brazil nuts, but in the process of producing these products part of the original forest is modified, often harming the plants and animals that live there. Tropical forests, though, have value far beyond that derived from these obvious harvests. The fish found in their rivers and lakes and the animals living in their forests provide sources of protein for the local population. The rich diversity of plants and animals found in tropical forests as well as their scenic beauty make them a favorite destination for tourists. In addition, tropical forests are reservoirs of genetic diversity, play an important role in maintaining the stability of the world’s atmospheric gases, and help control hydrological cycles on local, regional, and global scales.

The benefits that people receive from nature are known as “ecosystem services,” And they are often free-of-charge. For example, the water needed to drink, cook, grow plants, and raise animals is provided by the world’s ecosystems for nothing—the costs are added when the water and other products are transported to the consumer. Because monetary values are not placed on ecosystem services, they are often under appreciated and exploited as if they will last forever. But what if a value for what nature provides for human use and development is calculated and then charged to the consumer? If people have to pay the real cost of what they are using, we believe they will then appreciate ecosystem services and will seek to conserve the resources they depend for living such as water and air. As well, it would be a balancing mechanism for those who use a disproportionate share of these services which, in theory, belong to everyone of this and future generations.

Another economic concept to consider is the risk of “externalities,” which are defined as costs incurred (negative) or benefits received (positive) by third parties in business transactions. An important negative externality of tropical forest destruction is the release of carbon into the atmosphere when forests are cleared for agriculture or other uses. The carbon released plays a major role in climate change. The number of people who are harmfully affected by these negative externalities far outweigh the limited number of individuals who benefit from the selling of crops and meat from the cleared land (positive externalities).

Because ecosystem services are so important to humans as well as to all life on Earth, their value is viewed by scientists as one of the hot topics of conservation biology. As a result, many scientific papers have been published in this field of conservation biology. To help others understand the vital role that unspoiled nature plays in our lives, we have added a bibliography and links to Web sites that provide information about ecosystem services on the Garden’s Osa Web Site. Understanding these concepts and developing a willingness to pay for ecosystem services may be the only way to insure that tropical forests will still be available to provide ecosystem services for future generations.

For over 100 years, The New York Botanical Garden has been dedicated to preserving and protecting the environment, and that mission is more important than ever for the entire world, not for just the Osa Peninsula.