Botanical Behemoth

Posted in Around the Garden, Gardens and Collections on August 14 2012, by Matt Newman

In late summer, the NYBG‘s Enid A. Haupt Conservatory becomes the home of a botanical behemoth, one of the largest leaved plants in the world. And each year, visitors find themselves caught off guard by the delightful weirdness of this tropical oddity: Victoria amazonica. Originally from the Amazon River basin, it’s long since become an iconic display in our tropical water lily pond.

In late summer, the NYBG‘s Enid A. Haupt Conservatory becomes the home of a botanical behemoth, one of the largest leaved plants in the world. And each year, visitors find themselves caught off guard by the delightful weirdness of this tropical oddity: Victoria amazonica. Originally from the Amazon River basin, it’s long since become an iconic display in our tropical water lily pond.

Named for Britain’s Queen Victoria in the nineteenth century, the structure of the largest of water lilies is a bit like a kiddie pool (and often as big as one). Its broad, smooth leaves can stretch to nearly ten feet in diameter, forming expansive discs with sharply upturned edges that, again, make it look as though you could drop one in your backyard with a few gallons of water and a pool noodle. At maturity, their short-lived flowers can reach 15 inches across, opening white on the first evening as females, and pink on the second as males. It’s a brief display; the flowers (hopefully) attract pollinating beetles to do nature’s work, then sink below the water’s surface almost as abruptly as they emerged.

Sink with the flowers and you’ll witness what I’ll call an iceberg effect–there’s more going on below than there is above. The underside of the pads are covered from one side to the next in thick structural ribs, over and between which jut hundreds of sharp spines to protect the plant from herbivorous swimmers. The cell-like design was actually the inspiration for Joseph Paxton‘s famed Crystal Palace in London, which at nearly one million square feet was the largest glass building of the 19th century.

The entire structure is connected to an underwater stalk which can snake over 20 feet down to its base. Together, these features combine to push up a leaf that can support up to 80 pounds on its own. But with an almost paper-thin leaf consistency, you’d have to spread that weight out over a large surface area to keep from turning the disc into a donut. As such, I’m going to go ahead and ask that nobody try to balance any small children on one of these lily pads–it’s been done before elsewhere, but safety first.

While some South American cultures have been known to roast and eat the seeds of the plant, you’re not going to find many practical uses for it beyond its ornamental qualities. That’s unless you happen to be an abnormally large frog (this being the internet, I can’t really make any assumptions). But as with the smaller species of Nymphaea, growing this plant at home isn’t as hopeless an effort as it probably looks, so don’t drain your swimming pool in desperation just yet.

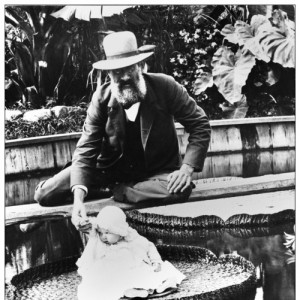

William Tricker, a Kew-trained aquatic gardener of the 19th century whose plant distribution business still operates today, discovered early on that Victoria amazonica tends to grow only so large as its container allows. “Last year a few plants that were not wanted were allowed to remain in eight-inch pots,” he wrote, “where they produced flower buds and one perfect flower, and would have continued to flower had they not been removed.”

Maybe it wouldn’t look as silly on your 2013 seed list as you first thought, huh?

Of course, this Amazonian lily pad is just one in the large family known as Nymphaeaceae. Surrounding it now are dozens of other cultivars in the tropical pool, across the way from the hardy pool where the NYBG cultivates the water lilies of Monet’s Garden. August and September are the height of the season for these aquatic show-offs, so be sure to take in both displays when you stop to visit the exhibition. And, again, fight the urge to see if they’ll hold your weight–we leave the wading to our horticulturists.

Click through to see more about Monet’s water lilies and the lotuses that nearly became the focus of his art, as well as a video on the upkeep of the impressive Victoria lily pads.

Header and footer images courtesy of Amy Weiss.