A Climb Into Paradise

Posted in From the Field on March 8 2013, by Scott Mori

Scott A. Mori has been studying New World rain forests for The New York Botanical Garden for over 35 years. He has witnessed an unrelenting reduction in the extent of the tropical forests he studies and as a result is dedicated to teaching others about this species rich ecosystem. His most recent book is Tropical Plant Collecting: From the Field to the Internet.

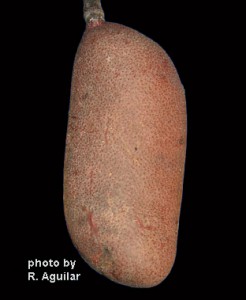

One of the most beautiful arboreal observations I have made during my long career occurred during an ascent into a large tree, one that happened to be adjacent to a legume tree scientifically named Hymenaea courbaril–more commonly known as the stinky toe tree. It was given this repugnant name because of the similarity of its fruits to a malodorous human toe. While botanical literature had already reported at the time that this species relied on bats for pollination, I wanted to confirm this observation by climbing a nearby tree from which I could see into the canopy as night fell, just as nocturnal animals started to make their appearances.

I was especially eager to make this climb because one of my research focuses has been the interactions between bats and the plants pollinated and dispersed by them. This was a rare opportunity to observe the crown of this 115-foot-tall tree in full flower, and as my job was to document the species that occur in the lowland forests of central French Guiana, as well as to discover the interactions that the local plants have with animals, I could not pass it up.

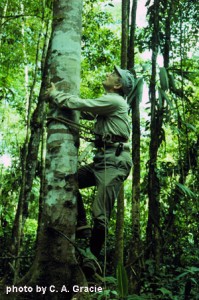

The climb was difficult because the diameter of the lower part of the trunk was at the upper limit of my climbing spikes, and the trunk had expanded and looked damaged 30 feet above the ground–perhaps as the result of a lightning strike. I listened carefully for the sound of wood cracking as I approached that spot and, with trembling legs, climbed around that mental and physical obstacle. Once past the bulge, the trunk became more slender, and I had easily reached 60 feet above the ground when a ferocious squall hit, causing the tree to sway back and forth–and me to tremble even more! Caught in a deluge of rain, I made a nervous and hasty retreat to the safety of the ground and returned to camp, where I eased into my hammock and worried throughout the night about the climb I would attempt the next evening.

The weather was clear the next day as I climbed toward the canopy at 4:30 p.m., settling into position to observe the stinky toe tree’s flowers as they opened. At first, I could only see a few hummingbirds visiting the flowers, but by 5:00 p.m. hundreds of them as well as an equal number of stunningly colorful perching birds were swarming over the canopy, showing flashes of brilliant color as they hovered over and perched on the branches to feed on nectar. I was thrilled to see such an impressive sight even though the visitors were birds, and not the bats that I had expected to document pollinating flowers.

About an hour after sunset, I heard the sounds of animals moving through the canopy, and when they entered the stinky toe tree I perceived three pairs of eyes moving up the trunk toward the flowers. I directed my light toward one of the three animals and was astounded to see a kinkajou staring back at me. Although I did not actually witness these arboreal animals visiting flowers, I suspect that they had purposely come into the tree to feast on the abundant nectar produced by them. Unfortunately, I did not observe bats pollinating the flowers or even entering the tree that evening, but others have made credible observations that bats are the main pollinators of the stinky toe tree. Although I would have loved to have seen pollinating bats, I would not trade my experience of enjoying so many beautiful birds visiting so many flowers over such a short time!

Although there is a myriad of co-evolved relationships between flowers and the plants that pollinate them in the tropics, these partnerships are seldom one-to-one. For example, if a plant has evolved a reward–in this case nectar–to attract pollinators such as the bats I had hoped to see, other animals will exploit that resource as well; in this case, these opportunists take the form of birds and kinkajous. There may be an evolutionary explanation for this–visitation by pollinators other than those to which the flowers are adapted allows flowers to be pollinated even if the more specialized pollinators are not present.