Floras are Never Complete

Posted in Science on May 20 2013, by Scott Mori

Scott A. Mori is the Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany at the New York Botanical Garden. His research interests are the ecology, classification, and conservation of tropical rain forest trees. His most recent book is Tropical Plant Collecting: From the Field to the Internet.

In telling the tale of one of the great Amazonian explorers, C.V. von Martius, I wrote that, “… Martius was carrying with him 20,000 botanical specimens which served, and continue to serve, as the basis for countless botanical studies, including Flora Brasiliensis which remains the only published complete Flora of Brazil to this day.” To clarify, I was not suggesting that Flora Brasiliensis contains all Brazilian species, but that it is the only Brazilian Flora that included all documented plant species in Brazil at the time of its writing. In fact, there are at least twice as many species known in Brazil today as there were back then!

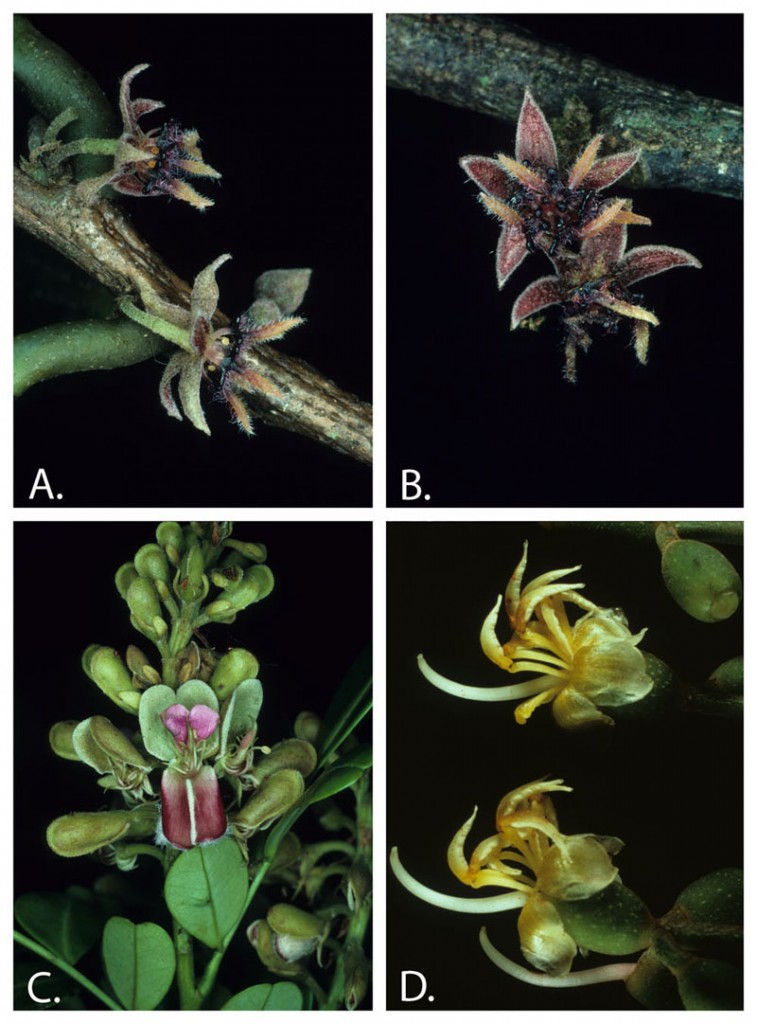

A/B. New species Byttneria morii

C. Monopteryx inpae, previously known only from central Amazonian Brazil

D. Miconia cacatin, placed in the wrong genus when first published

But what is a Flora? And how does it relate to another common botanical publication, the monograph? Floras and monographs are two of the many products produced by plant taxonomists at The New York Botanical Garden’s Institute of Systematic Botany. Traditionally, a Flora is a book describing all plants in a given geographic area, while a monograph treats all species of a particular group of plants throughout its geographic range. I capitalize “Flora” to distinguish it from “flora,” which alludes to all of the plants in an area rather than a book about the plants of that area.

But why are Floras never complete? In the first place, the area covered by a Flora often harbors new species that have not been named scientifically, or have scientific names but have not yet been found in the area covered by the Flora. This is especially true in tropical areas. For example, in our Guide to the Vascular Plants of Central French Guiana, we discovered 70 species new to science and 200 named species never before found in the region, all over the course of three decades of study.

In addition to these discoveries, the knowledge about the plants of a given floristic region continues to improve. Flowers, fruits, and seedlings are collected for species that once lacked this information; data on the flowering and fruiting of species is collected; a better understanding of morphological variation is achieved; chromosome, molecular, and chemical data are applied to help understand speciation; and new biotic relationships are revealed—such as which pollinators visit the flowers and what dispersal agents carry away the seeds.

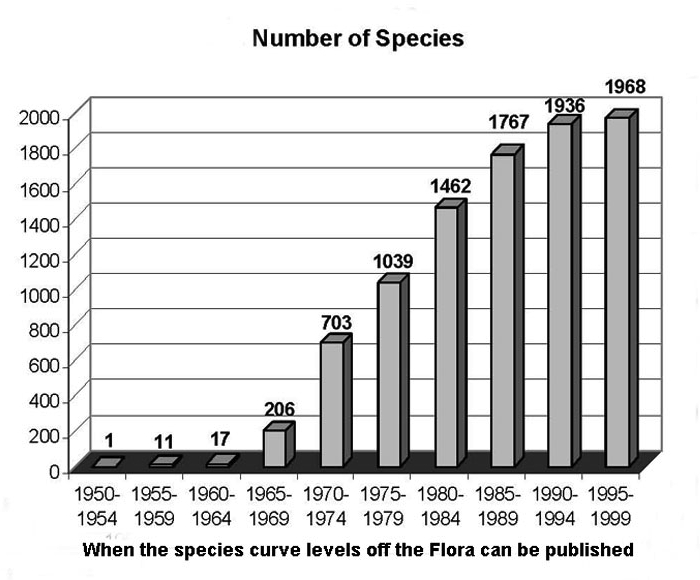

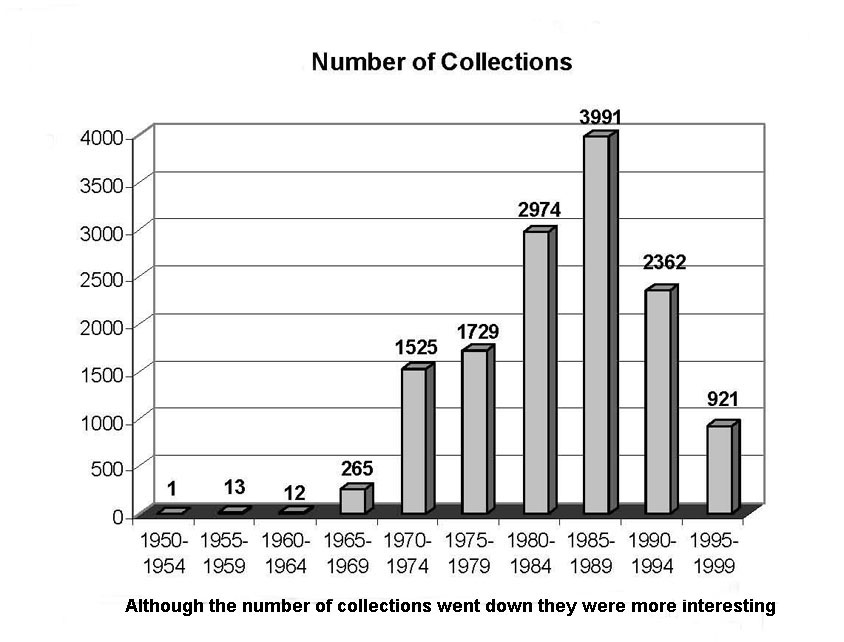

A well-planned floristic project is based on a collecting plan that includes expeditions in all habitats during all seasons. As the expeditions increase, the number of species added to the floristic area per expedition decreases—but the value of each collection goes up. The reason for the latter is that all of the easy-to-collect plants have already been gathered, leaving trees, woody canopy vines, rare plants, and those that fruit or flower for short periods as the last to be discovered. When the graph of a collection over time begins to level off, that is the time to get the working manuscript ready for publication. A hard copy Flora is out-of-date the day it is published, and cannot be updated until the next printed edition.

However, new technology allows Floras to be dynamic. They can be updated when needed, and new information is available online as soon as it is entered into the database. As one example, when new specimens are collected they are geo-referenced using a GPS device, and the new locality instantly appears on the database-driven website. Another strength of an electronic Flora is that its information can generate a hard copy Flora on demand for those who request it.

However, new technology allows Floras to be dynamic. They can be updated when needed, and new information is available online as soon as it is entered into the database. As one example, when new specimens are collected they are geo-referenced using a GPS device, and the new locality instantly appears on the database-driven website. Another strength of an electronic Flora is that its information can generate a hard copy Flora on demand for those who request it.

I hope this helps you to better understand the importance of Flora Brasiliensis and the undertaking of modern Floras. If you ever find yourself looking for a better explanation of something I discuss, feel free to leave your questions in the comments!