Sculpting the Land

Posted in Adult Education on March 12 2014, by Sonia Uyterhoeven

Sonia Uyterhoeven is the NYBG’s Gardener for Public Education.

Our spate of presentations from international gardening savants continued in February with British landscape architect Kim Wilkie, who joined us for the second of our annual Winter Lectures. At face value he may seem mild-mannered, but make no mistake: Wilkie loves to play in the mud. He shifts massive amounts of soil to sculpt the landscape in a very literal fashion.

Our spate of presentations from international gardening savants continued in February with British landscape architect Kim Wilkie, who joined us for the second of our annual Winter Lectures. At face value he may seem mild-mannered, but make no mistake: Wilkie loves to play in the mud. He shifts massive amounts of soil to sculpt the landscape in a very literal fashion.

Wilkie began his discussion by explaining how he infuses his contemporary ideas with historical perspectives. One source of inspiration is Mother Nature. He paid tribute to the powerful influence of ice and water, and the role of erosion in shaping the landscape. After this long, punishing winter, most of us will remember ice and water as a combined nuisance, reflecting on the piles of snow that buried our cars and blocked sidewalks. Wilkie, however, had a much more romanticized view of nature, presenting images of graceful contours carved into the land by winding rivers and glacial erosion.

In his quintessentially British Oxbridge manner, Wilkie related the fascinating chronology of both the military and spiritual tradition of moving massive amounts of earth to create man-made fortifications and construct sites for burial, solace, and worship. His slides carried us back in history with a sublime visual tour of this Northern European landscape custom.

Wilkie then launched into his own projects. The scale of his undertakings paired with his massive ambition is impressive. The first project he highlighted was a run down estate home, Heveningham Hall in Suffolk, that was being renovated by its new owners. They had reacquired the estate’s original 6,000 acres and hired Wilkie to restore the landscape to its former glory.

The Heveningham estate has a regal horticultural pedigree: the famous 18th-century landscape architect, Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, had been called in to draft a design for the property. The plan was drawn up but never implemented, leaving Wilkie with the distinguished responsibility of executing the design two centuries later.

While Wilkie’s role in the wider landscape was one of an interpreter, he was able to adopt a more actively creative role in the immediate area around the impressive estate home. The ground adjacent to the great hall rose sharply by 30 feet, creating a sunken garden behind the home that looked awkward and out of scale. Rather than fighting with the land, Wilkie worked with the sharp contours to create a graceful, fan-shaped grass terrace garden, the form of which is reminiscent of the mountainous terrain of Asian rice terraces.

Along the side of the house, Wilkie placed a 50-meter reflecting pool that doubled as a heated swimming pool. The clean lines and large scale of the water feature worked well with the sculptural form of the newly carved landscape. The result is a perfect balance between a stately home and an energetic modern landscape, opening up views and restoring a sense of grandeur to the rolling British countryside.

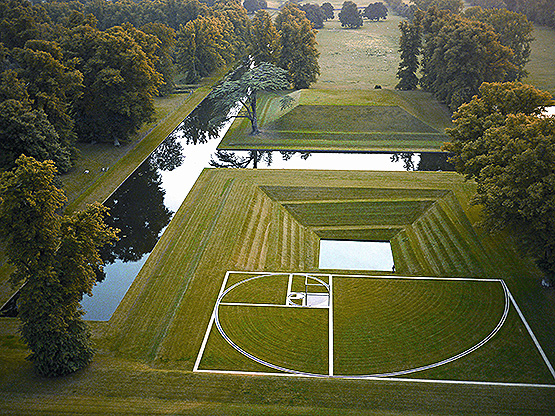

Wilkie’s designs are not only refreshingly innovative, but also incredibly user-friendly. While restoring the property of the Duke of Buccleuch at Broughton House in Northamptonshire, Wilkie created a private/public space that acts as an escape, an exploratory maze, a recreational site, and an amphitheater.

The Duke had a large pyramid mound on this property that was built centuries ago as part of a classical garden, rising above the space like a small mountain. He felt it looked out of place in the landscape and asked Wilkie for his advice, who in turn proposed building an inverted pyramid that sunk into the ground to complement the extant landscape feature.

Soil was shifted around and a 50-meter, inverted square pyramid was carved into the ground. A substantial grassy ledge winds its way down the side of the pyramid to meet a pool created at the bottom. At the base of the pool is a stage that can rise out of the water and serve as a concert venue. The pyramidal structure was dubbed Orpheus, after the Greek legend who sought to retrieve his wife from Hades with his divine music.

Wilkie’s audience at the NYBG was curious about the mechanics behind creating such magnificent landscape sculpture, and the speaker’s lecture ended with a personal Q&A session. Questions ranged from the practical “how do you mow the grass on the pyramid and keep crisp, clean edges on your terraces” to larger questions of ecology, habitat, and modern intervention in landscape design.

Even if you weren’t able to make it to Kim Wilkie’s lecture, you still have one last chance. Come and join us on Thursday, March 20 for our third and final installment in the 14th Annual Winter Lecture Series. Washington D.C.-based designer Thomas Rainer will be talking about designing with native plants in ways that artfully interpret natural landscapes, rather than trying to imitate them.