Small Treasures in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library

Posted in From the Library on June 6 2016, by Jane Lloyd

Jane Lloyd is a volunteer in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library of The New York Botanical Garden.

Visitors to a garden are often impressed by the showy, brightly colored roses and barely notice the smaller, humbler daisies. Likewise, visitors to the Rare Book Room in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library of The New York Botanical Garden often admire the large folio volumes of botanical illustrations by renowned botanical artists, but are unaware of the treasures among the smaller print volumes on the shelves. For the last two years I’ve been examining the names written and bookplates pasted in these books, trying to trace the histories of these books and to identify their former owners. This detective work has revealed that many books have led fascinating lives.

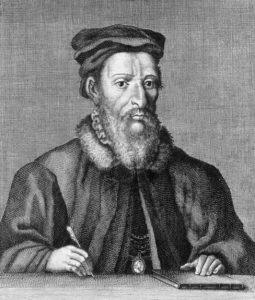

One book that has had a particularly noteworthy life is Apologia adversus amathum lusitanum by Pietro Mattioli, first published in 1558. Mattioli (1501–1577) was a well-known physician, botanist, and natural scientist from Siena, Italy. His book is a discussion of another book, first published in 1557, In Dioscoridis Anazarbei de materia medica libri quinque, enarrationes eruditissimae by Lusitano Amato (Juan Rodrigo Del Castel-Branco) (1511–1568), a well-known Jewish-Portuguese physician and natural scientist. Amato’s book is a discussion of De materia medica, written in the first century A.D. by the Roman physician Dioscorides (c.A.D. 40–90). De materia medica was a comprehensive compilation and description of plants and their derivatives and of animal and mineral substances used as medicines at that time and was one of the most important reference books on medical substances in the Western world for 1600 years.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, every doctor, botanist, and natural scientist would have owned copies of these titles as important reference books.

The LuEsther T. Mertz Library’s copy of Mattioli’s book was acquired by the Library just over a century ago. It is a small book—the size of a modern paperback—and has been rebound in a brown and red binding that has deteriorated with age. There are two small, oval bookstamps imprinted in black ink on the title page. One bookstamp has the image of a spotted cat in the center and a printed legend in Latin in a border around the edge: EX.BIBLIOTH.LYNCAEA.FEDERICI.CAESI.L.P.MARCHMONT.CAEI.II.—“From Library Lyncaea” followed by a name. Research soon revealed that the name is Federico Cesi (1585–1630), member of a prominent aristocratic family in Renaissance Italy. Cesi became interested in science as a boy. In 1603 he and three friends founded the Lyncean Academy to study nature by direct observation. Over time other Italian scientists joined the Academy. The most important new member was Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), who joined in 1611. Members of the Academy met in Cesi’s palazzo in Rome to discuss scientific and administrative matters and plan future publications. When Cesi died in 1630, the Academy disbanded and his wife sold his library.

The second oval stamp on the title page of this book has a coat of arms with a large-brimmed hat above it and the capital letters BA below it in white on a black ground. It is the stamp of the library of Cardinal Alessandro Albani (1692–1779), a leading Italian patron of the arts and collector of Classical antiquities, who acquired this, and possibly other books, from Cesi’s library. After the Albani family died out in the middle of the 19th century the books in the Albani collection were sold at public auction.

It’s not hard to imagine the books in Cesi’s library being taken down from the shelves and left lying open on a table as members of the Lyncaean Academy debated scientific matters in his home. Perhaps Galileo himself turned the pages of this book for information on some point in one of their lively debates. In any case, this book that I am holding was once held and opened by some of the greatest scientists of the late Italian Renaissance.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; public domain.