Sowing Beauty in the Meadow

Posted in From the Library on June 5 2017, by Esther Jackson

Esther Jackson is the Public Services Librarian at NYBG’s LuEsther T. Mertz Library where she manages Reference and Circulation services and oversees the Plant Information Office. She spends much of her time assisting researchers, providing instruction related to library resources, and collaborating with NYBG staff on various projects related to Garden initiatives and events.

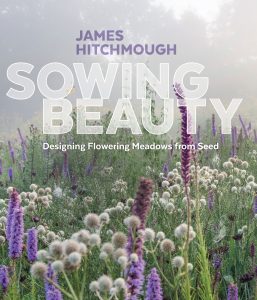

Sowing Beauty: Designing Flowering Meadows from Seed is a new book from James Hitchmough and Timber Press. Hitchmough is an established author of popular garden writing as well as a respected academic. Sowing Beauty offers readers a hybrid of academic and popular writing related to meadow garden creation featuring plants from around the world.

Sowing Beauty: Designing Flowering Meadows from Seed is a new book from James Hitchmough and Timber Press. Hitchmough is an established author of popular garden writing as well as a respected academic. Sowing Beauty offers readers a hybrid of academic and popular writing related to meadow garden creation featuring plants from around the world.

In addition to an introduction and appendices, the book itself is separated into sections titled “Looking to nature for inspiration and design wisdom,” “Designing naturalistic herbaceous plant communities,” “Seed mix design, implementation, and initial establishment,” “Establishment and management,” and “Case studies of sown prairies, meadows, and steppe.”

Sowing Beauty is an attractive and interesting book, but a hard one to classify. The book centers around Hitchmough’s unique style and somewhat radical practice of sowing meadows from seed. Sowing Beauty is home gardener-friendly in terms of content, detailing the process of meadow-sowing from start to finish. Readers learn to create seed mixes, sow their seeds, and maintain their meadows over time.

While the book is ostensibly about naturalistic meadow gardens, Hitchmough advocates very strongly for the use of non-native plant species, especially in the case of gardens created in urban areas for the pleasure of humans. As he has written on the topic of how humans interact with nature, this human-first approach is understandable. Continuing the case for non-natives, Hitchmough also makes note of the fact that in certain studies, non-native plants performed similar ecosystem functions as their native counterparts. Hitchmough’s point, here, is that non-native plants can serve a purpose both for the enjoyment of people and as a part of a healthy ecosystem.

Both of these points have merit, although Hitchmough certainly underplays the devastating effect that invasive species in particular can have on the biodiversity of native plant communities. He cites a study conducted in the UK by Chris Thomas and Georgina Palmer that found, “at the national level, naturalized exotic plant species had no measurable negative impact on native plant biodiversity.” That may well be the case for this study, but there are innumerable additional studies that belay Hitchmough’s implication that invasive species aren’t all that bad, really. Hitchmough writes, “There is a whole industry in many countries in praise of the native, so it is difficult to challenge the mantra of ‘native good, alien bad,’ but this is what the urban ecology scientific literature is increasingly doing. Once you move beyond romanticism and political native tags, ecologically speaking exotics and natives behave in pretty much the same sort of ways.” In essence, provided that one is thinking of the ecosystem as a whole as opposed to the plant organisms themselves, what’s the big problem with using non-native species? In support of this idea, Hitchmough blurs the lines between non-native species and invasive species, which is arguably irresponsible and opaque.

While it is true that not all non-native species are invasive, downplaying the tremendous amount of evidence that some non-natives are absolutely having a negative impact on intact native ecosystems is very detrimental. To actively encourage the use of non-natives and invasives suggests dangerous ignorance about the complex webs of interactions that make up ecosystem-level functions. Local extinctions of plants, insects, and other animals, and the disruption of food webs and other delicate ecosystem-level interactions, all of which can occur in response to invasive species, can lead to permanent global extinction and potentially have profound impacts on cycles and systems that affect the quality of human life, in addition to that of many other life forms. Hitchmough’s cavalier attitude is appalling.

The issues of native versus non-native or invasive species aside, Sowing Beauty is a densely-packed and interesting book featuring plant palettes from many regions and designs from various gardens. While the book includes Australian, American, European, African, and Asian plant palettes, the gardens profiled are nearly all located in the United Kingdom. While the text itself is written as a narrative, it seems to have good utility as a reference book. Readers might browse a few pages about the alpine meadows of Eurasia or the South African steppe. They might review detailed charts about emergence rates based on watering patterns. Perhaps they will read about successes and challenges at the locations of Hitchmough’s various projects, enjoying the photographs of beautiful and robust plant communities. Used in tandem with other books about meadow gardening, Sowing Beauty offers a different perspective and style for home gardeners and professional horticulturists alike.

In the end, Sowing Beauty is worth the read if you have an interest in meadow gardening and in plant communities fostered primarily for human enjoyment.