Montana’s Pioneer Botanists

Posted in From the Library on August 17 2017, by Esther Jackson

Esther Jackson is the Public Services Librarian at NYBG’s LuEsther T. Mertz Library where she manages Reference and Circulation services and oversees the Plant Information Office. She spends much of her time assisting researchers, providing instruction related to library resources, and collaborating with NYBG staff on various projects related to Garden initiatives and events.

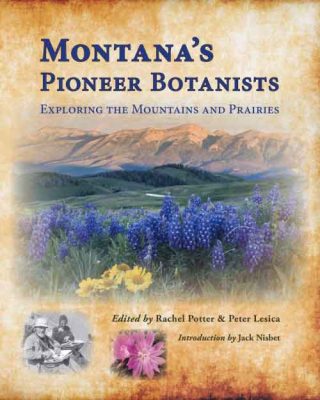

Montana’s Pioneer Botanists: Exploring the Mountains and Prairies is a new book from editors Rachel Potter and Peter Lesica, with an introduction by Jack Nisbet.

Montana’s Pioneer Botanists: Exploring the Mountains and Prairies is a new book from editors Rachel Potter and Peter Lesica, with an introduction by Jack Nisbet.

Montana’s Pioneer Botanists, a collection of biographies of regional botanists working in Montana, is the type of book that I really enjoy. Collections like this are essential for documenting and remembering important regional workers while sharing their legacy with the world. As is the case with other books of this ilk, some of the figures profiled in Montana’s Pioneer Botanists are known to a wider audience (Meriwether Lewis, for example), while others are beloved local heroes. In his introduction, Nisbet writes, “The subjects here hold a keen awareness of those who came before them, lending a strong sense of continuity to the entire project.” This continuity travels beyond Montana documenting ties between Montana botanists and the wider world, including the New York Botanical Garden. For example, botanist Robert Statham Williams (1859-1945) collected plants in Montana for years before joining the New York Botanical Garden in 1899. John Leiberg (1853-1913), another botanist profiled in this work, was a correspondent of Elizabeth Britton throughout his career.

In an excellent earlier review of this work, Dr. Patricia Holmgren, Director Emerita of New York Botanical Garden Herbarium, wrote: “Hear ye, hear ye! Librarians, botanists, herbarium curators, historians, book aficionados! You are going to love Montana’s Pioneer Botanists, a gold mine of information about botanical exploration in Montana, beginning with indigenous people and ending with Klaus Lackschewitz (1911-1995).” Indeed, this book, although very specific in its focus, does have wide appeal for anyone who is interested in botany, history, or biography. Dr. Holmgren’s review also includes mention of some of the interesting anecdotes within this text, one involving NYBG’s own Elizabeth Britton. My singular disappointment with this book, not a criticism of the editors but of the history of science more generally, is that only two women are profiled within the thirty-one essays in this work. As the editors included biographies only for scientists who are deceased, this is cited as the reason for the imbalance.

Thanks are due to Potter and Lesica for completing this work. It’s an excellent addition to the library’s collections at NYBG, and will hopefully serve as inspiration for others to accomplish future projects of this nature.