The Wild World of Laura Ingalls Wilder

Posted in History, People, Shop/Book Reviews on October 3 2017, by Joyce Newman

Joyce H. Newman is an environmental journalist and teacher. She holds a Certificate in Horticulture from The New York Botanical Garden.

Most of us know Laura Ingalls Wilder as the author of The Little House series. But now a wonderful new book by NYBG instructor and garden historian Marta McDowell reveals little-known facts about Wilder’s other life—as a settler, farmer, and gardener.

Most of us know Laura Ingalls Wilder as the author of The Little House series. But now a wonderful new book by NYBG instructor and garden historian Marta McDowell reveals little-known facts about Wilder’s other life—as a settler, farmer, and gardener.

In The World of Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Frontier Landscapes That Inspired The Little House Books (Timber Press, $27.95), McDowell creates an intimate, colorful, and witty portrait of the writer who cherished her gardens and whose gardening life was shaped by the prairie lands that have largely disappeared today. (McDowell is also the author of Beatrix Potter’s Gardening Life, Emily Dickinson’s Gardens, and All the Presidents’ Gardens.)

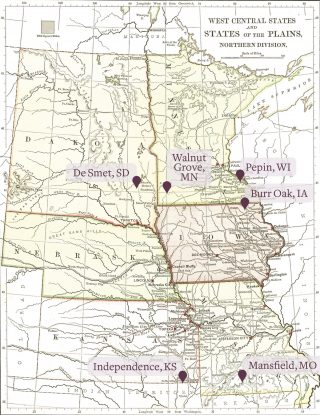

This year marks the 150th anniversary of Wilder’s birth. Her life began in 1867 in a Wisconsin log cabin, a frontier baby whose pioneer parents had cleared a forest to make a farm—“the quintessential American beginning,” says McDowell. McDowell traces Wilder’s upbringing and adulthood in the first part of the book—several chapters follow her from Wisconsin, to Kansas, Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota, Missouri, and other places where Wilder’s daughter, Rose Wilder Lane (her prairie rose), ultimately lived.

McDowell organizes the second part of the book for travelers and gardeners who might want to go see some of Wilder’s gardens or who want to grow the plants Wilder grew. A big bonus: At the end of the book, there’s a long plant list with common and botanical names of plants that Wilder grew, plus where they are mentioned in her novels, and whether they were grown at Rocky Ridge Farm in Mansfield, Missouri. For the record, McDowell notes that violets, in particular, appear in almost every book written by Wilder.

I recently asked McDowell some questions about writing her book. (Some parts of this interview have been condensed and edited for length.)

Q. How did you get the idea for the book?

A. The idea came in an unusual way, at least in my experience. It was the first week of March 2015. I had just sent in the submission for All the Presidents’ Gardens and was ready for a break. During a phone conversation, my editor, Tom Fischer at Timber Press, dangled the suggestion of Laura Ingalls Wilder in front of me. The South Dakota State Historical Society Press had released an annotated version of Wilder’s previously unpublished autobiography, Pioneer Girl, in 2014, and it was a surprise best seller. After an initial print run of something like 10,000 copies, well over 100,000 copies sold! This is every publisher’s dream. Then, the minute I started reading up on Wilder’s life, I was hooked.

There was one catch. Timber Press wanted to publish the book during the 150th anniversary of Wilder’s birth. Thus, unlike my normal three-year cycle for research-writing-production, I had to do this at a sprint, especially given the number of places I needed to see.

Q. The original illustrations by Garth Williams and Helen Sewell are so beautiful. Did you select the illustrations and other graphics for your book?

A. I do all of the image sourcing and selection myself. It is a part of the work that I love. It lets me dig around in archives, like the glorious collection in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library, and to indulge myself by acquiring some antiquarian books for my own shelves. I think that because I choose my own images, they fit my words.

I do have one secret weapon—maybe superhero is a better word—for artwork. My friend Yolanda Fundora is a gifted graphic artist, and I hire her to work with me on every project. She can do things like take imperfect antique images that I have scanned out and make them publication ready.

Q. What did you enjoy most about doing the book?

A. I kept uncovering surprises about Wilder’s relationship to places and plants, surprising because they resonate with 21st-century sensibilities. She depicted the natural world where she lived—eight or ten places depending on how you count—each with a unique combination of flora, fauna, terrain, weather, describing what we now would call a biome or ecosystem. She mourned the loss of the prairie and wild places. And while she participated in the steadily advancing mechanization of American agriculture, the Ingalls and Wilder families practiced sustainable techniques on the farm and in the home. They saved seeds, composted and amended their soil, used green manure cover crops, and understood the delicate balance of livestock, food crops, and their growing conditions. They prepared and preserved foods in ways that are everywhere now, from lifestyle blogs to the shelves of gourmet food boutiques and increasingly to supermarket aisles.

Those topics let me dive into other areas of interest: The history of canned food; the development of the mason jar; the sources and origins of seeds; and much more.

Q. What did you find challenging about the book?

A. First, the commute was tough. Wilder and her husband, Almanzo, lived in New York State (almost at the Canadian border), Wisconsin, Kansas, Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota, and Missouri, plus one year on the Florida panhandle—the only homesite I haven’t seen yet. Her papers are housed in the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library in West Branch, Iowa. So it meant that I spent a lot of time on the road.

Second, I am less familiar with plants of the plains and prairies (not to mention the Florida panhandle), so I had to contact experts. And I must say that folks across the country were universally helpful and responsive: Folks at the various Ingalls and Wilder homesite museums; professionals and scientists from Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds, Seed Savers Exchange, South Dakota Game, Fish & Park, Kansas Forest Service, the University of Kansas, Old House Gardens Heirloom Bulbs, Prairie Moon Nursery, and a big shout out to the NYBG Plant Information Team.

Q. Do you have a favorite plant from those described in your book?

A. Growing the plants that I am researching is a great part of my job, and one that gets me away from the keyboard and back outdoors. Since starting on this book I’ve added sweet potatoes, ground cherries, and blue flag irises (Iris versicolor and I. virginica) to my own garden with good results.

_______________________

Marta McDowell will be at NYBG to discuss her new book with landscape architect Thomas Rainer on Wednesday, October 11, from 11 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Register here.

is “Aunt Molloy’s Ground Cherry” the same plant as the orange “Chinese Lantern”? and are they eatable? thank you