Inside The New York Botanical Garden

Scott Mori

Posted in Science on January 31 2013, by Scott Mori

Scott A. Mori has been studying New World rain forests for The New York Botanical Garden for over 35 years. He has witnessed an unrelenting reduction in the extent of the tropical forests he studies and as a result is dedicated to teaching others about this species rich ecosystem.

[Not a valid template]

I still stand in awe each time I see the cannon ball tree (Couroupita guianensis), a member of the Brazil nut family. In fact, it is such an astonishing plant that I am nominating it as the most interesting tree on Earth (disclaimer: I am a specialist in the Brazil nut family and my nomination may be biased). After you read this essay, I would like to know if you agree with me—if not, I challenge you to nominate a tree, tropical or temperate and from any part of the world, that you feel is more interesting than this marvel of nature.

Read More

Posted in Science on January 24 2013, by Scott Mori

Scott A. Mori has been studying New World rain forests for nearly 40 years. He has witnessed an unrelenting reduction in the extent of the forests he studies and, as a result, has become concerned about their future. The following blog is based on a chapter in his recent book, Tropical Plant Collecting: From the Field to the Internet.

The future of plant and animal diversity in Latin American rain forests depends on an understanding of how fragile the plant and animal interactions found in this ecosystem are. The relationships between plants and animals in the tropics are so closely co-evolved that man’s utilization of tropical forests always results in loss of biodiversity. After a 40-year career of botanical exploration in the New World tropics, I conclude that human beings had little to do with the evolution of biodiversity anywhere on the planet, especially in the tropics, and, as Thomas Friedman said in his book Hot, Flat, and Crowded, “We are the only species in this vast web of life that no animal or plant in nature depends on for its survival–yet we depend on this whole web of life for our survival.”

The future of plant and animal diversity in Latin American rain forests depends on an understanding of how fragile the plant and animal interactions found in this ecosystem are. The relationships between plants and animals in the tropics are so closely co-evolved that man’s utilization of tropical forests always results in loss of biodiversity. After a 40-year career of botanical exploration in the New World tropics, I conclude that human beings had little to do with the evolution of biodiversity anywhere on the planet, especially in the tropics, and, as Thomas Friedman said in his book Hot, Flat, and Crowded, “We are the only species in this vast web of life that no animal or plant in nature depends on for its survival–yet we depend on this whole web of life for our survival.”

I believe that increasing human population and consumption throughout the world is not compatible with the preservation of the world’s biodiversity, but that rings especially true in the tropics. Moreover, many tropical forests grow on soils that are so nutrient poor they will never support high human populations without massive inputs of fertilizers and pesticides. If tropical areas are not productive enough today to provide significant resources to a world population of 6.5 billion, what makes humans think that they will be able to contribute to supporting a population of nine to 11 billion humans by 2050? The consumptive power of a resident of today’s Amazon rain forest is several orders of magnitude greater than that of the pre-Colombian inhabitants who based their economy on fertilizer- and pesticide-independent agricultural systems. In short, residents of the tropics–and the world in general–will not be able to protect biodiversity at the level it needs if both human population growth and consumption are not controlled.

Read More

Posted in Science on January 16 2013, by Scott Mori

Scott A. Mori has been studying New World rain forests for The New York Botanical Garden for over 35 years. He has witnessed an unrelenting reduction in the extent of the tropical forests he studies and as a result has become interested in the ecosystem services provided by them.

Hurricane Sandy left a path of fallen trees throughout its course, including over 100 at The New York Botanical Garden. Included in this devastation at the NYBG was a 101-foot-tall red oak thought to be 200 years old; this majestic tree provided the right habitat for spring-blooming plants in the Azalea Garden. Repeated storms with such force and frequency are making people ask if the storms could be related to global warming.

Hurricane Sandy left a path of fallen trees throughout its course, including over 100 at The New York Botanical Garden. Included in this devastation at the NYBG was a 101-foot-tall red oak thought to be 200 years old; this majestic tree provided the right habitat for spring-blooming plants in the Azalea Garden. Repeated storms with such force and frequency are making people ask if the storms could be related to global warming.

Climatologists have demonstrated that impressive swings in climate have taken place over the course of earth’s history—for example, the northeastern United States has been covered by glaciers during some periods and by tropical forests at other times. Because of these extremes of climate, it is difficult to say with certainty what the cause of such violent weather is. The proximate, or direct, cause of Hurricane Sandy was the convergence of three “normal” weather patterns: 1) a tropical storm with very strong winds coming from the south; 2) a trough of low pressure from the Arctic that strengthened the storm as it moved north; and 3) a block of high pressure in the northeastern Atlantic which forced the storm inland. In contrast, the more difficult question is: “What are the ultimate causes that make storms stronger and more frequent?”

Read More

Posted in Science on January 11 2013, by Scott Mori

Scott A. Mori has been studying New World rain forests for The New York Botanical Garden for over 35 years. He has witnessed an unrelenting reduction in the extent of the tropical forests he studies and as a result has become interested in the ecosystem services provided by them.

Manisha Sashital, a student in Environmental Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, worked on a botanical glossary under the supervision of Dr. Mori as an intern at the Garden this past summer.

Just like languages, the sciences have vocabularies that must be mastered before their literature can be understood. Without understanding vocabulary, one cannot speak or write a language—just like one can not understand the morphology and anatomy of plants; their ecological relationships with other plants and animals; and their interactions with the environment in which they live without understanding the terms that describe the features of plants and their interactions. Learning the terminology of Botany is frustrating to beginners and experienced botanists alike because the vocabulary is vast, there are many synonyms for the same terms, and terms are a combination of Latin, Greek, and English words. There are numerous botanical glossaries available, for example the classics: A Glossary of Botanical Terms by B. D. Jackson and Botanical Latin by William T. Stern, and too many others to mention in this blog. Why then is there a need for another glossary?

Just like languages, the sciences have vocabularies that must be mastered before their literature can be understood. Without understanding vocabulary, one cannot speak or write a language—just like one can not understand the morphology and anatomy of plants; their ecological relationships with other plants and animals; and their interactions with the environment in which they live without understanding the terms that describe the features of plants and their interactions. Learning the terminology of Botany is frustrating to beginners and experienced botanists alike because the vocabulary is vast, there are many synonyms for the same terms, and terms are a combination of Latin, Greek, and English words. There are numerous botanical glossaries available, for example the classics: A Glossary of Botanical Terms by B. D. Jackson and Botanical Latin by William T. Stern, and too many others to mention in this blog. Why then is there a need for another glossary?

The answer is that electronic glossaries provide those with an interest in botany access to more information than hard copy publications. For example, electronic glossaries can be illustrated with more images than hard copy publications because of the high costs of printing, especially of images in color, and they can be immediately corrected when a mistake is brought to the attention of the authors. Electronic glossaries are instantaneously available to anyone with a connection to the internet, and links can be made to definitions of other terms related to a particular term under consideration. In addition, electronic glossaries can be attached to electronic keys to break down complex terminology used to identify unknown plants; for example, if a choice in a key asks if the ovary of a flower is superior or inferior, a link can be provided to these terms in a glossary where they are defined and illustrated.

Read More

Posted in Around the Garden on September 26 2011, by Scott Mori

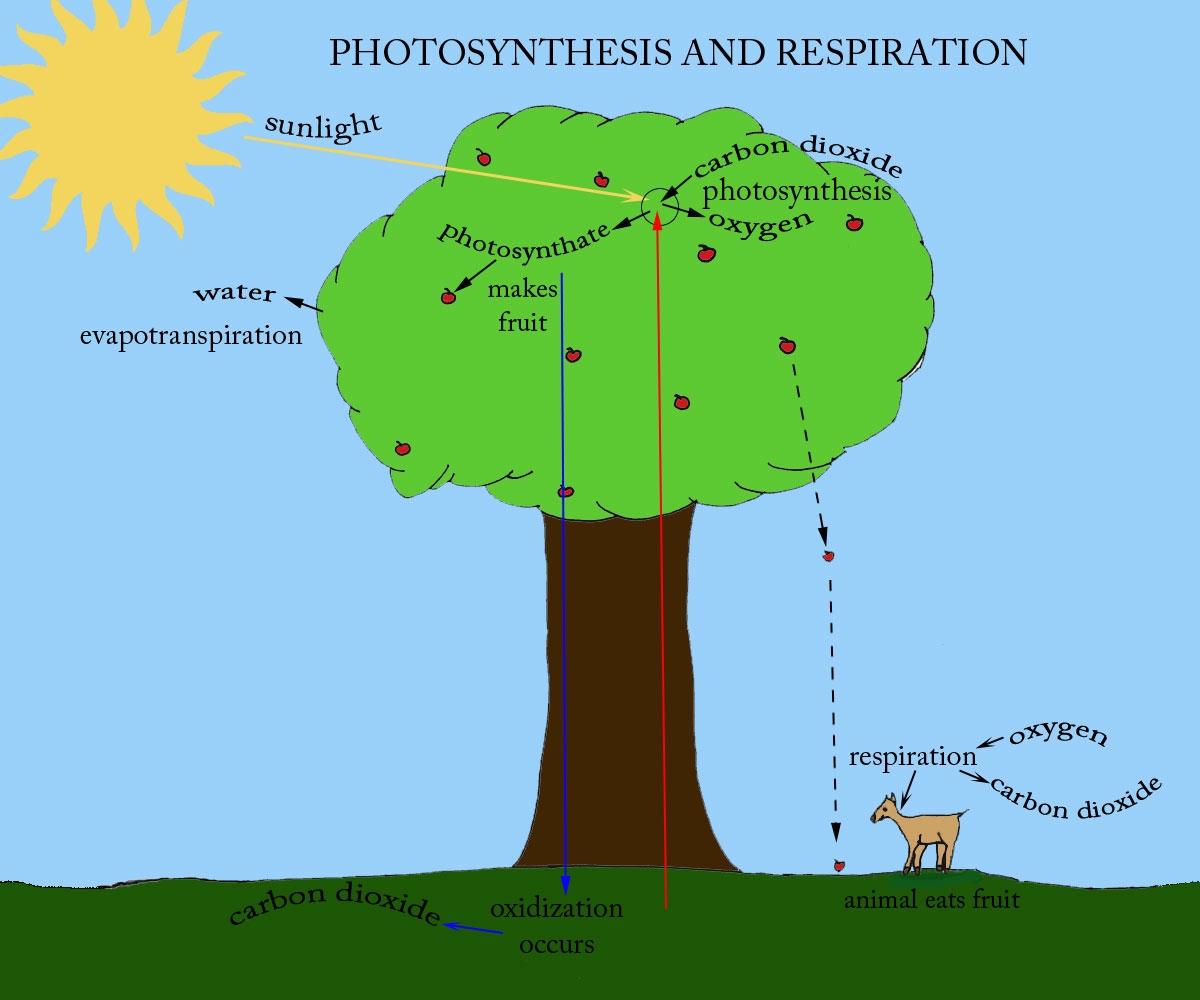

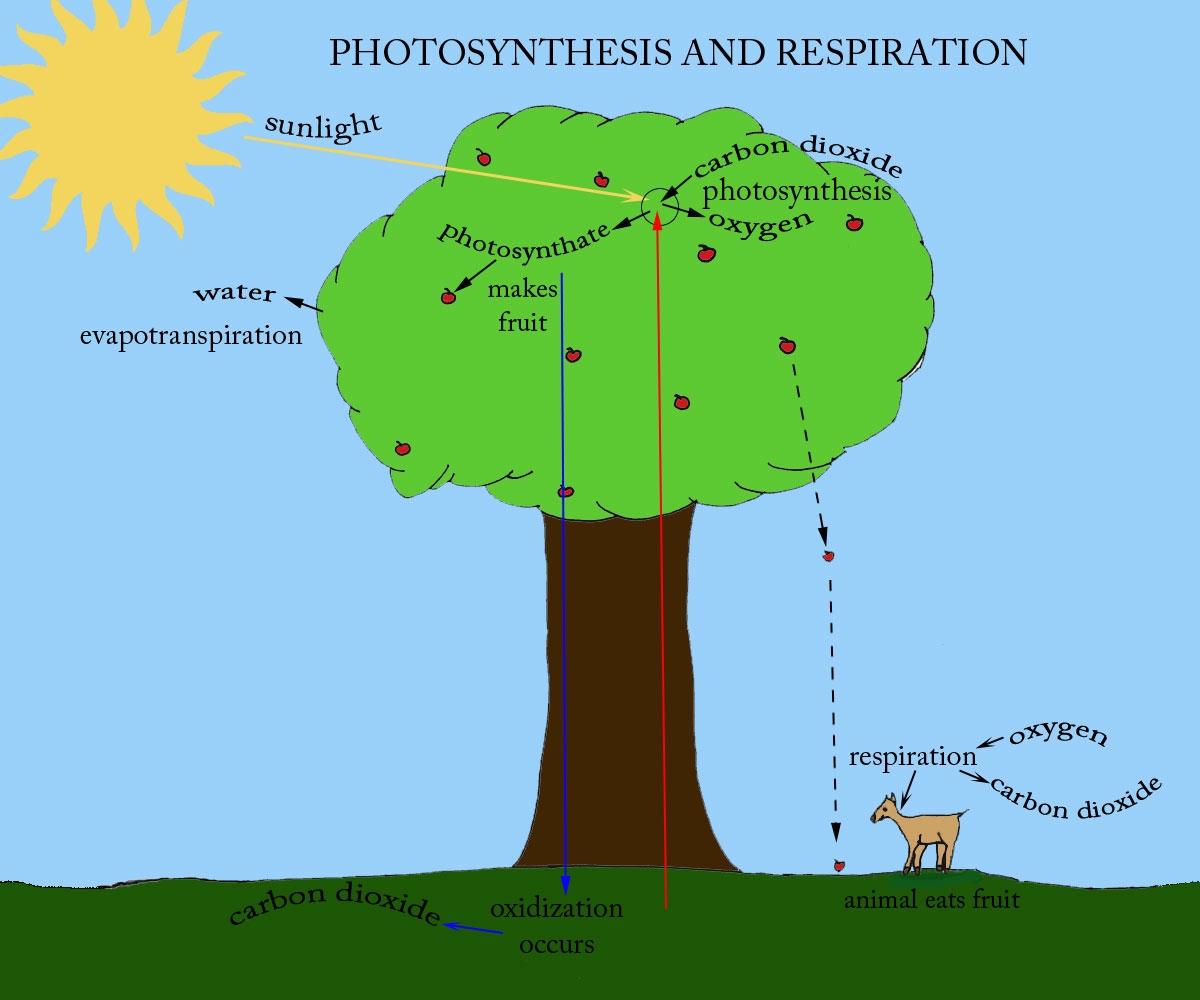

Manisha Sashital, a student in Environmental Engineering and Environmental Policy at Carnegie Mellon University, worked on a botanical glossary under the supervision of Dr. Mori at the Garden this summer. As part of her internship she prepared a cartoon illustrating the relationship between photosynthesis and respiration.

Manisha Sashital, a student in Environmental Engineering and Environmental Policy at Carnegie Mellon University, worked on a botanical glossary under the supervision of Dr. Mori at the Garden this summer. As part of her internship she prepared a cartoon illustrating the relationship between photosynthesis and respiration.

Scott A. Mori has been studying New World rain forest plants for The New York Botanical Garden for over 35 years. His interest in tropical forests as carbon sinks have been stimulated by his studies of trees in old growth tropical forests.

Scott A. Mori has been studying New World rain forest plants for The New York Botanical Garden for over 35 years. His interest in tropical forests as carbon sinks have been stimulated by his studies of trees in old growth tropical forests.

Global warming has become one of the planet’s deadliest threats. Since the Industrial Revolution, carbon dioxide concentrations have risen from 280 ppm to nearly 390 ppm, with the potential to reach 550 ppm by 2050 if carbon emissions from fossil fuel combustion are not controlled. The earth has experienced major warming three times; but the Cretaceous warming period took place over millions of years and the Paleocene/Eocene warming happened over thousands of years. In contrast, today’s temperature changes are happening over decades. As a result, many species, perhaps even humans, may not be able to adapt to such rapid and high increases in temperature. One concern that is generally unknown to the public is that photosynthesis, the source of energy for nearly all organisms on the planet, shuts down at around 104° F. Mankind’s extreme disruption of the carbon cycle is causing and will continue to cause serious consequences for life on earth.

Carbon dioxide levels contribute to global warming through the greenhouse effect. Greenhouse gases trap radiation from the sun in the atmosphere, which causes global temperatures to rise because the radiation is not reflected back out of the atmosphere. The reason for today’s increased atmospheric carbon levels can be attributed to the combustion of fuels used for the production of electricity and in transportation, both of which are essential to modern societies; as well as to cutting and burning forests throughout the world. Since there is no precedent for the rapidity of current temperature increases, it is impossible for humans to predict which areas of the world will be affected and at what magnitude. The unpredictability of global warming makes it an especially serious environmental problem.

Carbon dioxide levels contribute to global warming through the greenhouse effect. Greenhouse gases trap radiation from the sun in the atmosphere, which causes global temperatures to rise because the radiation is not reflected back out of the atmosphere. The reason for today’s increased atmospheric carbon levels can be attributed to the combustion of fuels used for the production of electricity and in transportation, both of which are essential to modern societies; as well as to cutting and burning forests throughout the world. Since there is no precedent for the rapidity of current temperature increases, it is impossible for humans to predict which areas of the world will be affected and at what magnitude. The unpredictability of global warming makes it an especially serious environmental problem.

Rain forests as well as other vegetation types play an important role in reducing the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Annually, plants in tropical rain forests around the world take in millions of tons of carbon dioxide and release millions of tons of oxygen through photosynthesis, and this balances the respiration of microbes, plants, and animals, which take in oxygen and expel carbon dioxide. As seen in the accompanying cartoon, plants take in carbon dioxide and water and use the energy of the sun to create carbohydrates that are, in turn, oxidized to produce the energy needed for plants to sustain themselves. The carbohydrates are also the building blocks plants use to make leaves, stems, flowers, and fruits. Oxygen, the byproduct of respiration, is used by organisms to break down ingested carbohydrates to produce the energy needed for them to grow and reproduce. Mankind’s extreme disruption of the carbon cycle is and will continue to have serious consequences for life on earth.

Read More

Manisha Sashital, a student in Environmental Engineering and Environmental Policy at Carnegie Mellon University, worked on a botanical glossary under the supervision of Dr. Mori at the Garden this summer. As part of her internship she prepared a cartoon illustrating the relationship between photosynthesis and respiration.

Manisha Sashital, a student in Environmental Engineering and Environmental Policy at Carnegie Mellon University, worked on a botanical glossary under the supervision of Dr. Mori at the Garden this summer. As part of her internship she prepared a cartoon illustrating the relationship between photosynthesis and respiration. Scott A. Mori has been studying New World rain forest plants for The New York Botanical Garden for over 35 years. His interest in tropical forests as carbon sinks have been stimulated by his studies of trees in old growth tropical forests.

Scott A. Mori has been studying New World rain forest plants for The New York Botanical Garden for over 35 years. His interest in tropical forests as carbon sinks have been stimulated by his studies of trees in old growth tropical forests.