Inside The New York Botanical Garden

Science

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on February 11 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

February 2, 2011; Seno Courtenay, northern arm, 54°30’S, 71°20’W

With today came the realization that the days are racing by. Initially it seemed like we had lots of time, but now the calendar is creeping up on us. We have today and the next three days before we head back to Punta Arenas (about a 17 hour trip).

With today came the realization that the days are racing by. Initially it seemed like we had lots of time, but now the calendar is creeping up on us. We have today and the next three days before we head back to Punta Arenas (about a 17 hour trip).

Today was a great collecting day, we all came back delighted with what we had found. Blanka has nicknamed this locality The Enchanted Forest. We are in an eastern arm of Seno Courtenay where several small rivers emerge from what looks like a floodplain forest. There is supposedly a glacier-fed lake upriver, but not one of us has made it that far! At the beginning of the morning I was disappointed when I entered the forest; it seemed like it contained only the standard mosses I have become used to seeing.

Today was a great collecting day, we all came back delighted with what we had found. Blanka has nicknamed this locality The Enchanted Forest. We are in an eastern arm of Seno Courtenay where several small rivers emerge from what looks like a floodplain forest. There is supposedly a glacier-fed lake upriver, but not one of us has made it that far! At the beginning of the morning I was disappointed when I entered the forest; it seemed like it contained only the standard mosses I have become used to seeing.  However, as I worked through the forest, the humidity increased as did the number and biomass of epiphytes. The trunks and branches of most trees were sheathed in bryophytes, and even twig epiphytes increased in diversity.

However, as I worked through the forest, the humidity increased as did the number and biomass of epiphytes. The trunks and branches of most trees were sheathed in bryophytes, and even twig epiphytes increased in diversity.

More from The Enchanted Forest below.

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on February 10 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

February 1, 2011; Seno Courtenay, 54°37’S, 71°21’W

The ship engines started about 6:30 a.m. By this point in our journey, this rouses no one from their bunks except the crew. However, as soon as the engines are cut off it means we have arrived at our next field site and everyone hurries up to breakfast. Every morning for breakfast there is fresh bread, sometimes baked, sometimes fried. It’s a great way to start the day.

The ship engines started about 6:30 a.m. By this point in our journey, this rouses no one from their bunks except the crew. However, as soon as the engines are cut off it means we have arrived at our next field site and everyone hurries up to breakfast. Every morning for breakfast there is fresh bread, sometimes baked, sometimes fried. It’s a great way to start the day.

Mornings are mostly proving to have reasonable weather, but usually by 1-2 p.m. it starts to rain harder and the winds pick up. This morning we arrived in Bahía Murray on the east side of Isla Basket. The island is named for Fuegia Basket, the name Charles Darwin’s expedition gave to an indigenous young woman that they essentially kidnapped and took to England to “civilize.” The weather–just light continuous drizzle–was not an issue, and we all went ashore to collect. We split into a few groups to cover more habitats. Juan decided to try and reach a peak that rises to about 1600-1700 feet and took our satellite modem with him in an attempt to send out my daily blogs. He got within 50 feet of the summit but couldn’t continue because the rocks were steep and crumbling. Needless to say, the modem still couldn’t find a satellite.

Mornings are mostly proving to have reasonable weather, but usually by 1-2 p.m. it starts to rain harder and the winds pick up. This morning we arrived in Bahía Murray on the east side of Isla Basket. The island is named for Fuegia Basket, the name Charles Darwin’s expedition gave to an indigenous young woman that they essentially kidnapped and took to England to “civilize.” The weather–just light continuous drizzle–was not an issue, and we all went ashore to collect. We split into a few groups to cover more habitats. Juan decided to try and reach a peak that rises to about 1600-1700 feet and took our satellite modem with him in an attempt to send out my daily blogs. He got within 50 feet of the summit but couldn’t continue because the rocks were steep and crumbling. Needless to say, the modem still couldn’t find a satellite.

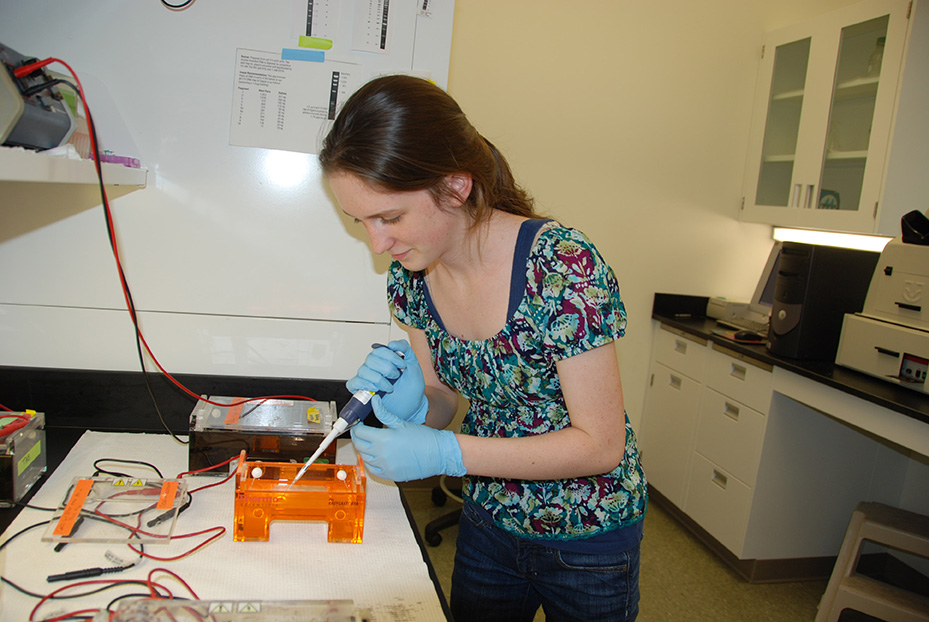

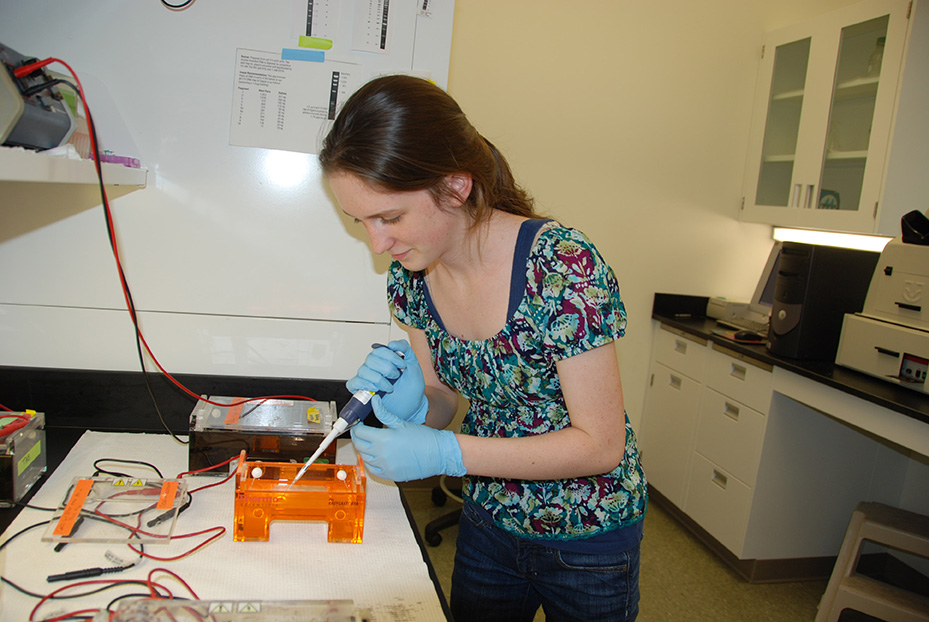

Scientists at work! More below.

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on February 9 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 31, 2011; canal between Isla Georgiana and Isla Clementina, 54°41’S, 71°45’W

January 31, 2011; canal between Isla Georgiana and Isla Clementina, 54°41’S, 71°45’W

The engines started early and we only traveled about 1 1/2 hours before they stopped again. Because of the short time I assumed that we must have just headed north to the Brecknock Peninsula. However, much to my delight we were actually in a small sound on the northwest side of Isla Sidney. The gods must have been smiling on us, because for one of these barrier islands, the weather was great. The sun came and went, and only an occasional shower passed. This was particularly surprising because as we were getting into our rain gear before leaving the ship it had been sleeting.

We split into three groups and headed off in different directions. I went alone to a beautiful southern beech gallery forest along a small, rocky steam. As I worked up the stream it eventually opened up and the rocks in the stream changed from being liverwort-covered in the shade, to moss-covered in the sun. As much as I am enjoying the company of my colleagues, it was nice to be alone for a few hours, especially in such a beautiful place. When we returned to our pick-up point in the early afternoon, everyone was very pleased both with what they had found, as well as with the weather (especially after the previous day).

We split into three groups and headed off in different directions. I went alone to a beautiful southern beech gallery forest along a small, rocky steam. As I worked up the stream it eventually opened up and the rocks in the stream changed from being liverwort-covered in the shade, to moss-covered in the sun. As much as I am enjoying the company of my colleagues, it was nice to be alone for a few hours, especially in such a beautiful place. When we returned to our pick-up point in the early afternoon, everyone was very pleased both with what they had found, as well as with the weather (especially after the previous day).

The team hits the bryophyte jackpot! More below.

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on February 8 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 30, 2011; Unnamed sound on south side of Brecknock Peninsula, NW of Isla Georgiana, 54°36’S, 71°49’W

January 30, 2011; Unnamed sound on south side of Brecknock Peninsula, NW of Isla Georgiana, 54°36’S, 71°49’W

Early in the morning the crew moved the ship to a harbor on the northeast side of Isla London, one of the islands in direct contact with the weather from Antarctica. After two days of glorious weather, Matt was beginning to wonder if the weather I had told him to prepare for was just a myth. He soon found out how true my warnings had been. The morning started out a bit windy and overcast, but without rain.  One group set out to with the intention of ascending Horatio Peak, while Blanka and I headed to a rocky outcrop in the opposite direction. As the zodiac neared the shore the wind started to pick up, and soon became a strong steady wind came out of the southwest, gusting so hard at times to literally blow me off my feet. Fortunately, as we worked up the slope the wind was at our backs and helped propel us as we scrambled over the vegetation, walking on top of the canopy of dwarf beeches as on the previous morning.

One group set out to with the intention of ascending Horatio Peak, while Blanka and I headed to a rocky outcrop in the opposite direction. As the zodiac neared the shore the wind started to pick up, and soon became a strong steady wind came out of the southwest, gusting so hard at times to literally blow me off my feet. Fortunately, as we worked up the slope the wind was at our backs and helped propel us as we scrambled over the vegetation, walking on top of the canopy of dwarf beeches as on the previous morning.

In short order, though, a heavy, horizontal, rain began. I had become separated from Blanka, all I could do was hope that she was able to find shelter. (I later discovered she had also tried to find me to let me know she was fine). On the side of a ridge I plopped down and sank into the shrubs; I was completely below the surface of the dwarf tree canopy, but could see out. The rain blew in sheets as spray from the sea was whipped up and blown ashore. The water dripping down my face tasted salty. Because of the high winds, it was too dangerous to walk around. For about a half an hour I remained immersed in the shrubs and watched as the rain and wind blasted the island. I was glad I was not up on an exposed ridge like the other group, and hoped they had found shelter. After some time, the winds became less gusty and died down, and the rain softened so that it no longer felt like pellets as it hit my skin.

In short order, though, a heavy, horizontal, rain began. I had become separated from Blanka, all I could do was hope that she was able to find shelter. (I later discovered she had also tried to find me to let me know she was fine). On the side of a ridge I plopped down and sank into the shrubs; I was completely below the surface of the dwarf tree canopy, but could see out. The rain blew in sheets as spray from the sea was whipped up and blown ashore. The water dripping down my face tasted salty. Because of the high winds, it was too dangerous to walk around. For about a half an hour I remained immersed in the shrubs and watched as the rain and wind blasted the island. I was glad I was not up on an exposed ridge like the other group, and hoped they had found shelter. After some time, the winds became less gusty and died down, and the rain softened so that it no longer felt like pellets as it hit my skin.

Meet the rest of the crew below!

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on February 7 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 29, 2011; Isla Aguirre, Seno Quo Vadis, 54°34’S, 71°59’W

January 29, 2011; Isla Aguirre, Seno Quo Vadis, 54°34’S, 71°59’W

Our two days in Punta Arenas seemed to drag on after such a great first part of our expedition. However, it did mean we were able to pick up Matt and buy a few things to tweak the moss dryers. On the morning of January 28 we returned to the port to board our trusty ship. Going out onto the dock, the ship, which was sandwiched between a large naval vessel and a massive cruise ship, looked even smaller. A number of the passengers disembarking from the cruise ship stopped and asked what we were doing. As soon as I hear an American accent I tell them “Your tax dollars at work!” and briefly explain the project. I think it is important for them to know that their taxes pay for something more than war.

Shortly after we untied from the dock and headed south, once again motoring through the Straits of Magellan, a pod of at least ten dolphins joined our ship. They criss-crossed in front of our ship for over an hour, seemingly doomed to a collision which never came. The same time the sea was remarkably calm; even in canals where we had previously encountered violent water, the ship hardly rocked. The captain chose to take an inland passage rather than the more commonly used Cockburn Canal. We seemed, time and again, to enter into a dead end sound, only at the last minute to watch it turn into a previously invisible sound. A short time later the passage we had just come from had similarly disappeared. Going down these narrow waterways, as opposed to wide canals, gave us a better view of the incredible forests that march up the shores. Although continuously overcast, the evening light was almost luminescent and navigating through a veritable maze of islands was a special experience. Once again I delighted in Matt’s reaction to the astounding landscapes, as I had with the others in our group the previous week.

Shortly after we untied from the dock and headed south, once again motoring through the Straits of Magellan, a pod of at least ten dolphins joined our ship. They criss-crossed in front of our ship for over an hour, seemingly doomed to a collision which never came. The same time the sea was remarkably calm; even in canals where we had previously encountered violent water, the ship hardly rocked. The captain chose to take an inland passage rather than the more commonly used Cockburn Canal. We seemed, time and again, to enter into a dead end sound, only at the last minute to watch it turn into a previously invisible sound. A short time later the passage we had just come from had similarly disappeared. Going down these narrow waterways, as opposed to wide canals, gave us a better view of the incredible forests that march up the shores. Although continuously overcast, the evening light was almost luminescent and navigating through a veritable maze of islands was a special experience. Once again I delighted in Matt’s reaction to the astounding landscapes, as I had with the others in our group the previous week.

Before going to bed I spoke with the captain and explained the area we wished to cover and told him that it was his decision, based on navigability and weather, as to where we started. If we had relatively good weather, we would stop at the westernmost islands south of the Brecknock Peninsula; or if the weather looked bad, we would go to the eastern end of the area where sheltered sounds would allow us to still work. The far western islands have proven tricky in previous trips where it rained hard and incessantly with fog drifting across the area making it unsafe to get far from the ship. These islands have no land between them and Antarctica. However, it is this very climate–as harsh as it may seem when we are out collecting–that may well be encouraging the growth of mosses that we do not otherwise see in our region. During the night, most of us awoke as the ship hit rough waters and was buffeted about as we rounded the Brecknock Peninsula in seas open to Antarctic winds and storms. In the middle of the night, it almost seemed dreamlike.

Before going to bed I spoke with the captain and explained the area we wished to cover and told him that it was his decision, based on navigability and weather, as to where we started. If we had relatively good weather, we would stop at the westernmost islands south of the Brecknock Peninsula; or if the weather looked bad, we would go to the eastern end of the area where sheltered sounds would allow us to still work. The far western islands have proven tricky in previous trips where it rained hard and incessantly with fog drifting across the area making it unsafe to get far from the ship. These islands have no land between them and Antarctica. However, it is this very climate–as harsh as it may seem when we are out collecting–that may well be encouraging the growth of mosses that we do not otherwise see in our region. During the night, most of us awoke as the ship hit rough waters and was buffeted about as we rounded the Brecknock Peninsula in seas open to Antarctic winds and storms. In the middle of the night, it almost seemed dreamlike.

Bill Buck and his colleagues find themselves in a world of miniature trees. Read more below.

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on February 1 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 26, 2011, Punta Arenas, Chile

January 26, 2011, Punta Arenas, Chile

We awoke on the morning of January 25 in Seno Agostini, having arrived there at about 4 a.m. Initially the journey was rough because of strong winds and large swells. Standing on the deck, but huddled close to the cabin, I was in awe of the weather. Since childhood in Florida, the U.S. capital of lightning, I have loved violent weather. On this day, the wind howled and the boat was tossed and turned by the rough seas; every few seconds waves would crash over the deck. To be on a small ship amidst such weather is amazing. Of course it helps to have a ship that you have faith in and a reliable crew. A few of our group felt a bit queasy, but no real problems came up (pun intended). After about an hour and a half we entered a narrower channel and the seas were calmer. Only then was dinner served.

Coming out on deck the next morning the scenery was spectacular. We had come to this spot because in 1929 a Finnish bryologist, Heiki Roivainen, visited the site and, in an alpine stream, collected a moss that has not been found since. Because this is a moss that is part of Juan’s doctoral work, he was anxious to find it again. The site is called Mt. Buckland, and it rises to over 6,000 feet but is mostly snow-covered above. Supposedly the moss was collected at about 2,000 feet in an alpine stream. All around us rugged peaks rose to the sky, all with either snow or glaciers. At least for a short time the sun shone brightly.

So, optimistically, Jim and Juan headed up the slopes of Mt. Buckland. Blanka and I chose to visit a southern beech forest on the other side of the sound that had a large glacier at its back side. It was about a 20 minute zodiac ride across the sound but as soon as we hit the rocky beach we knew we were in a special place. Numerous small, glacier-fed streams wound their way through the landscape and occasional large rock outcrops promised multiple microhabitats for bryophytes. Once Blanka entered the forest, about 10 yards past the coastal scrub, it took me about an hour to get her to move ahead. The forest floor was carpeted with a thick layer of liverworts that swallowed our boots with every step. Trees were sheathed with bryophytes and lichens, often several times the diameter of the trunks themselves. We worked our way through the forest toward the glacier, marveling at the diversity and sheer biomass of bryophytes in the forest.

So, optimistically, Jim and Juan headed up the slopes of Mt. Buckland. Blanka and I chose to visit a southern beech forest on the other side of the sound that had a large glacier at its back side. It was about a 20 minute zodiac ride across the sound but as soon as we hit the rocky beach we knew we were in a special place. Numerous small, glacier-fed streams wound their way through the landscape and occasional large rock outcrops promised multiple microhabitats for bryophytes. Once Blanka entered the forest, about 10 yards past the coastal scrub, it took me about an hour to get her to move ahead. The forest floor was carpeted with a thick layer of liverworts that swallowed our boots with every step. Trees were sheathed with bryophytes and lichens, often several times the diameter of the trunks themselves. We worked our way through the forest toward the glacier, marveling at the diversity and sheer biomass of bryophytes in the forest.

Barberries, bryophytes, and icebergs, oh my! More below.

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on January 31 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 24, 2011, Seno Chasco, just north of isthmus to Brecknock Peninsula, Chile, 54° 34’S, 71° 39’W

January 24, 2011, Seno Chasco, just north of isthmus to Brecknock Peninsula, Chile, 54° 34’S, 71° 39’W

Last night, after I had finished my work for the day, I was enjoying the night out on the deck (i.e., a lull in the rain) and watching Blanka, Jim and Juan down in the hold putting their collections on the dryer. They have each been consistently excited about going out into the field everyday, no matter what the weather. Back on the ship they happily go through their collections. Watching their interest and energy makes me feel good that I am able to provide them with this opportunity. It also gives me something to look forward to, for those future expeditions when, in upcoming years, new teams of bryologists will accompany me to this spectacular region. Although it is something that never occurred to me before, this truly is one of the highlights of this project, being able to see the excitement on the faces of bryologists who have never seen such a mossy paradise before, and knowing that I could give them this gift (thanks to the National Science Foundation).

More on Cape Horn's mossy paradise below.

Posted in Science on January 28 2011, by Plant Talk

| Amy Litt is Director of Plant Genomics and Cullman Curator. |

Grace Phillips, a senior at Mamaroneck High School, has been named a finalist in the prestigious Intel Science Talent Search. Phillips worked as a Cullman intern at the Garden for more than two years with graduate student Rachel Meyer on research related to the domestication of the eggplant. It is for this research that she is being recognized. In March, Grace will travel to Washington, D.C.,–along with the 39 other finalists–to participate in final judging, display her work to the public, meet Nobel laureates, and to find out if she has won the top prize of $100,000.

Grace Phillips, a senior at Mamaroneck High School, has been named a finalist in the prestigious Intel Science Talent Search. Phillips worked as a Cullman intern at the Garden for more than two years with graduate student Rachel Meyer on research related to the domestication of the eggplant. It is for this research that she is being recognized. In March, Grace will travel to Washington, D.C.,–along with the 39 other finalists–to participate in final judging, display her work to the public, meet Nobel laureates, and to find out if she has won the top prize of $100,000.

In addition to being a tasty treat, the eggplant has been also cultivated for ages–from India, to China, and to the Pacific Islands–for the plant’s medicinal values. Hundreds, if not thousands, of local variations of the eggplant exist throughout Asia, varying widely in size, shape, color, and flavor; and are used medically for a variety of purposes. It is likely that the medicinal values of the eggplant come from a variety of potent antioxidant compounds found within the fruits.

Phillips studied what impact the role of centuries of human selection–based on taste and medicinal properties–have had upon the eggplant genome. This involved first studying the chemicals that are thought to be responsible for the gastronomic and therapeutic properties of the various local variations (also known as landraces). By correlating the presence of specific antioxidant compounds to specific tastes and medicinal attributes Phillips attempted to answer a simple question: Are certain medicinal uses of eggplants always associated with high concentrations of specific compounds?

After determining the various chemical compounds within the eggplants, Grace then began to study the genes that are directly related to the synthesis of these compounds, looking for correlations between gene activity and compound abundance. Phillips was then able to put all this information together and pose one final question: Are certain taste and medicinal qualities correlated with high levels of specific gene? Or, in other words: As humans selected for eggplants with specific culinary and therapeutic properties, what effect did this intervention have on the eggplant genome and on the plant’s gene functions?

Grace is one of seven finalists from New York State, second only to California’s 11 finalists. She appears to be the only finalist working in the field of plant sciences, and one of only a handful of students studying organismal diversity/evolutionary questions. Grace’s work continues a long heritage of scientific study at The New York Botanical Garden on questions of plant diversity, human-plant interactions, and plant conservation. Everyone here at the Garden applauds Grace’s fantastic work and wishes her the best of luck in March!

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on January 28 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 23, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Puerto Consuelo, Seno Chasco, Chile, 54° 32’S, 71° 31’W

January 23, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Puerto Consuelo, Seno Chasco, Chile, 54° 32’S, 71° 31’W

Although I am writing this blog daily, it is often impossible to send it. We were told that the modem that we rented would work anywhere, but in reality it needs a clear view to the north. Often times, though, our ship is anchored in a sheltered area with tall, snow-capped mountains on most sides of us. With the severe and changeable weather here, the saying “any port in a storm” takes on extra meaning! So, I continue to write and send them out whenever the modem decides it is in the mood.

Early this morning (5 a.m.) the captain moved the ship from our previous site to the sound directly west. When I awoke to the engine starting, I knew it would be 3-4 hours before we reached our next site, and that we could sleep in for awhile. Maybe an hour later it became obvious that we had left the protected sound for more open waters. The ship started rocking violently. For most of us, it was like rocking a baby in a cradle and put us back to sleep. Only one person felt a little queasy and had to take something for seasickness. Fortunately, so far, no one has actually gotten sick. In my previous trip to the region, on our second day our, we hit a large storm which crashed 12 foot waves over the ship for hours on end. As our bunkroom was transformed into a vomitorium, I was the only non-crew member who didn’t get sick. Since our bunkroom on this trip has minimal ventilation at best, it is a true blessing that this time no one has gotten sick.

It was immediately obvious when we entered the next sound, suddenly the waters were much calmer. At about 8:30 a.m., the ship stopped. I assumed that meant we were at our next site. Such was not the case. Rather, we were taking on fresh water. To do this, the ship will pull up to a waterfall and one of the crew scrambles up the cliff face with a plastic bucket that is outfitted with a hose coming out of the bottom of it. The bucket goes into the waterfall and the end of the hose is placed into the hatch of the water tank, on top of the ship. We are in a totally uninhabited place, one that gets around 12 feet of rain a year, much of which at higher elevations falls as snow. So even in mid-summer, given that there are no large mammals to pollute it, the snow-melt water is pure and cold, which is good because it is the only fresh water we have. After watching the crew member (José) go up the cliff face like a monkey, I told him now we just need to teach him to collect mosses!

Read more about Bill's adventures below.

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on January 27 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 22, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Seno Brujo,, Chile, 54° 30’S, 71° 32’W

January 22, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Seno Brujo,, Chile, 54° 30’S, 71° 32’W

Yes, we’re in the same place as yesterday. The captain of our ship said that last night, winds of 80 knots (88 mph) were expected, and so he did not want to take the ship out into open water. 88 mph!! That’s hurricane force winds, and indeed during the night the winds howled and the ship was buffeted about.

I got up in the night and went out onto the deck at 3:45 a.m. The deck was illuminated with moonlight, many stars were visible, and the snow glowed on nearby mountains; however, the wind was strong and I held onto the railing to make sure I wouldn’t be blown overboard. Moments like this, alone in the glory of nature, are the moments I treasure above almost everything else. When I came out again at 6:15 a.m., the sun had risen, the winds had died down and the sky was mostly clear. If nothing else, the weather here can change quickly.

By the time we were ready to go into the field, it had started to rain again, but this time only lightly, and the winds, and thus the sea, remained calm. We headed toward what we initially thought was a lake but instead turned out to be a shallow inlet of the sea, accessible by zodiac. We split up and Jim headed toward a large, glacier-fed waterfall because of his special interest in rheophytic bryophytes, those that grow on rocks in moving water. Some rheophytes are only in the water seasonally, following rain patterns, and others are permanently wet. Juan headed up the mountain, toward the snow, because the moss genus he is working on for his dissertation often grows on exposed rocks. Blanka collected along the shore of the small inlet, and I headed for the rocky peaks near the shore and the pockets of forest in more sheltered sites.

Learn more about the team's goal for this expedition below.

With today came the realization that the days are racing by. Initially it seemed like we had lots of time, but now the calendar is creeping up on us. We have today and the next three days before we head back to Punta Arenas (about a 17 hour trip).

With today came the realization that the days are racing by. Initially it seemed like we had lots of time, but now the calendar is creeping up on us. We have today and the next three days before we head back to Punta Arenas (about a 17 hour trip). Today was a great collecting day, we all came back delighted with what we had found. Blanka has nicknamed this locality The Enchanted Forest. We are in an eastern arm of Seno Courtenay where several small rivers emerge from what looks like a floodplain forest. There is supposedly a glacier-fed lake upriver, but not one of us has made it that far! At the beginning of the morning I was disappointed when I entered the forest; it seemed like it contained only the standard mosses I have become used to seeing.

Today was a great collecting day, we all came back delighted with what we had found. Blanka has nicknamed this locality The Enchanted Forest. We are in an eastern arm of Seno Courtenay where several small rivers emerge from what looks like a floodplain forest. There is supposedly a glacier-fed lake upriver, but not one of us has made it that far! At the beginning of the morning I was disappointed when I entered the forest; it seemed like it contained only the standard mosses I have become used to seeing.  However, as I worked through the forest, the humidity increased as did the number and biomass of epiphytes. The trunks and branches of most trees were sheathed in bryophytes, and even twig epiphytes increased in diversity.

However, as I worked through the forest, the humidity increased as did the number and biomass of epiphytes. The trunks and branches of most trees were sheathed in bryophytes, and even twig epiphytes increased in diversity.