Inside The New York Botanical Garden

Science

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on January 26 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 21, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Seno Brujo, Chile, 54° 30’S, 71° 32’W

January 21, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Seno Brujo, Chile, 54° 30’S, 71° 32’W

The weather caught up with us today. I’ve hardly mentioned the weather, up to this point, because it is such a part of the region that it’s easy to take it for granted. Prior to the trip I warned everyone to be prepared for temperatures around 50ºF, 40 mph winds, and rain. Until today we had been lucky. By that I mean, it has been cool, and somewhat windy, but with only occasional light rain. Here, this is considered good summer weather! Yesterday, our first full collecting day, the weather was cool and breezy with intermittent light rain. Last night when we were discussing the day among ourselves, some of our group hadn’t even noticed that it had rained at all, and it probably rained about a third of the time in the morning. But it was only a light rain and the vegetation is permanently wet, so a little more water was easy to overlook.

Early this morning we left Seno Bluff for the next sound to the west, Seno Sargazos. It was calm waters and overcast but not raining. Right after breakfast we went ashore and collected for several hours along a lake-fed river. I asked the Chileans what they would call the vegetation and was told it was called Magellanic tundra. What a good name! There were only patches of trees in small ravines, the landscape mostly consisted of tussocks of herbaceous plants and bryophytes about 2 feet tall that are very spongy underfoot, with holes between the tussocks. Walking was slow and treacherous. However, collecting was good and we found some real sub-Antarctic mosses.

During lunch we moved the ship to the next sound west, Seno Brujo. Our goal was to get to the southernmost end of it and then work up a river to a large lake we could seen on a map. I guess the rough seas between the two sounds should have been an indication that the weather was changing. When we arrived it was raining hard, but wasn’t too windy, and we decided to go collecting at least for a couple of hours. However, as we suited up in our rain gear, the weather worsened. Once we were standing out on the deck, ready to board the zodiac to go ashore, the rain became torrential and the wind picked up, driving the rain almost horizontally. When it hit your skin it felt like sleet because of the force as well as how cold it was.

The waters were rough with white tops being driven up by the wind. I made an executive decision that we would not go out in the afternoon, much to everyone’s relief. So, we’ll spend the night here tonight, in a slightly more sheltered cove, and go out in the morning. In this part of the world the weather is always a factor, but it is this very weather that results in such lush bryophytes. It is also the reason why the area is uninhabited and the landscape is so stunningly spectacular. But that can wait for morning!

Bill Buck’s Previous Reports From the Field

January 20, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Seno Bluff, Chile

January 18, 2011, Punta Arenas, Chile

January 16, 2011, Punta Arenas, Chile

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on January 21 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 20, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Seno Bluff, Chile, 54° 26’S, 71° 18’W

January 20, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Seno Bluff, Chile, 54° 26’S, 71° 18’W

After what seemed like an eternity of waiting (but was actually only five days), we were finally ready to leave.

We transported all our gear to the port and loaded it aboard our ship, the Don Jose Pelegrin, a commercial crabbing ship. The austral summer is when crabs breed, so crab fishermen are not able to fish, and we are able to rent this ship. In winter the ship works the sub-Antarctic seas catching the Southern Hemisphere equivalent of the Alaskan king crab (think World’s Deadliest Catch).

By any standard, this is a small ship (but obviously seaworthy). It is about 55 feet long by 17 feet wide; there is a small galley and from there you can access the bridge above or the bunkroom below by ladders. The bunk room is decidedly claustrophobic since I am unable (at 6 feet) to stand up in it. The 10 bunks are arranged in the shape of a capital E (my bunk is the lower one on the lower half of the upright of the E). It is something of a contortionist act to get in and out of the bunk, and once in the bunk there is well less than a foot from your body to the bunk above. Fortunately I am not inclined to claustrophobia since my attitude is that once I close my eyes, it doesn’t matter if it is 10 feet or 1 inch from me. At my request the hold that keeps the crabs has been fitted as a moss drying room. There is a small bathroom with a toilet and sink (no bathing facilities!) but today the toilet broke and so we need to go ashore in the woods for our bodily functions.

Bill and his colleagues finally set sail! Follow their adventures below.

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on January 18 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 18, 2011, Punta Arenas, Chile

January 18, 2011, Punta Arenas, Chile

Say hallelujah! On Sunday evening the barricades were lifted temporarily and I was able to get my luggage. Ah, the joys of clean clothes! The barricades were opened at about 7 p.m. and thousands of people flocked to the airport. However, the road to the airport was only to be open until 9:30 p.m., and the road from the airport (it is a divided highway) only until 11 p.m. So, Juan and Ernesto took advantage of the window and went to the airport to get not only my luggage but also their own. They were able to get my luggage and Ernesto’s, but Juan’s was locked in the DAP Airline office and no one was there from that airline. Fortunately, Juan only had collecting equipment there, and not his clothes. So, we are able to collectively provide him with what he needs.

On Monday, the protests continued, only growing larger. However, most stores opened, so we took advantage of it and did what little shopping we needed to do. The most interesting experience was when we went to a department store to buy pillows for our bunks on the ship. I had decided bringing a pillow was too bulky and easier just to buy here. We went to the bedding department and were told they were out of pillows. However, all the beds on the floor were made and had pillows on them. I pulled a pillow out of the pillow case and said that this was just fine with me. The sales person shrugged and led me to the cash register. Both Jim and Blanka followed suit and they bagged up our pillows. When I asked how much they were, he said they were free, a “souvenir” for us! So, they were out of pillows to sell, but what pillows they did have were free. Can you see that happening at Macy’s?!

Will the protests end? Will Bill and his crew ever be able to set sail? Found out below!

Posted in Bill Buck, From the Field, Science on January 16 2011, by William R. Buck

Ed. note: NYBG scientist and Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Botany, Bill Buck is currently on expedition to the islands off Cape Horn, the southernmost point in South America, to study mosses and lichens. Follow his journeys on Plant Talk.

January 16, 2011, Punta Arenas, Chile

We were originally scheduled to set sail and head out to sea tomorrow, but I’m hoping we’ll oly be delayed by a day. Two more of our group arrived last night, Blanka Shaw from Duke University and Jim Shevock from the California Academy of Sciences. All day there had been conflicting stories in the news about whether or not the protesters (who are protesting against the government for raising fuel prices) would allow a bus to take airline passengers from the airport to the barricade nearest the city. Because of the uncertainty, Juan Larraín, a graduate student at the Universidad de Concepción (in Concepción, Chile, just south of Santiago, where the earthquake was the worst last year) and our main Chilean collaborator on the project, borrowed a bicycle from a friend and went out to meet the flight. There was a bus, but initially they would not allow Blanka on it because she was too young. Fortunately, Juan was able to get her on the bus, along with Jim, and all their luggage. We had then arranged for a local student who will be on our trip, Ernesto Davis, to be waiting with a car on the other side of the barricade. About 9:30pm they arrived at the hotel, and Juan arrived about a half an hour later by bicycle. Neither Blanka nor Jim have ever been to South America and were excited to be here. At the barricade, as they walked through with their luggage, they even stopped to collect their first moss in Chile!

Needless to say, Blanka and Jim wanted to see the town today, and so Juan and I acted as tour guides, despite the fact that we both still have blistered feet from our walk from the airport a couple of days ago. While walking around the city, we came across a demonstration march around the central square, with its statue of Ferdinand Magellan. What was so interesting is that the protesters were not just young people, as one often sees at demonstrations. Rather, whole families, from grandparents to young children, were marching with flags and banners. It was very exciting to see such multigenerational activism.

We have an unconfirmed report that tomorrow there will be a flight from Puerto Williams. A group of 30-40 biologists are trapped there because of cancelled flights. They had been there for an inauguration ceremony for a new biological station. I had initially been invited but because of limited flights to Puerto Williams (and then mostly 18-seater prop planes) and limited accommodations (one hotel and a few bed-and-breakfasts) I bowed out. However, a few friends, including Bernard Goffinet from the University of Connecticut, as well as a group of students, four of whom are scheduled to join our expedition, are now trapped there awaiting a flight out. Tomorrow we’ll see if they get off of Isla Navarino. Assuming they do, and assuming I can finally get my luggage (still at the Punta Arenas airport), we’ll depart on Tuesday, January 18, just a day late.

Just moments ago a new rumor surfaced. We heard that until midnight the road to the airport would be open, but after midnight it would be shut tight, not even allowing pedestrians to walk there. I’m sure it’s to pressure the main airline, LAN Chile, to stop flying people to the city because they would just be trapped in the airport, plus their employees couldn’t get to work. On the chance this is true, Juan and Ernesto have gone to the airport to try and get our luggage. I hope it works because I’d really like some clean clothes. Of course that would mean the Puerto Williams group are still stuck! We have even discussed renting a helicopter (around $2,000 per hour) to retrieve the luggage.

Stay tuned for future developments ….

Posted in Science on January 5 2011, by Plant Talk

Deforestation followed by fires for creating agricultural fields and pasture releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at such an accelerated rate in the tropics that it is a major contributor to global warming. Photo by Scott Mori

Deforestation followed by fires for creating agricultural fields and pasture releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at such an accelerated rate in the tropics that it is a major contributor to global warming. Photo by Scott MoriThere are many different types of vegetation in the New World tropics. But rather than being a homogeneous whole, what grows where and when in these tropics is determined to a large extent by water availability and temperature variation. Climate change could potentially have a drastic impact on this region, especially on the rain forests. Liebig’s Law of the Minimum states that plant or animal growth is controlled by the scarcest resource in the environment; this is known as a limiting factor. For example, if a soil possesses all nutrients needed for plant growth except potassium, then the paucity of that nutrient will limit the potential growth of all plants except those that can grow in potassium-poor soils. Potassium is therefore a limiting factor for that soil.

More on the application of Liebig's Law to the destruction of Amazonian rainforests below.

Posted in Science, Video on December 1 2010, by Plant Talk

|

Rustin Dwyer is Visual Media Production Specialist at The New York Botanical Garden. |

The 50-acre native forest at The New York Botanical Garden is a very special section of New York City. It’s the largest and oldest remnant of old growth forest around, and it’s right here in the Bronx! It’s almost like a time machine that gives a faint glimpse of the past. Strolling through, it’s not hard to imagine the kind of environments Henry Hudson and the Lenape people walked through. (For more on this subject check out the WLC’s Welikia project, previously known as Manhatta)

The 50-acre native forest at The New York Botanical Garden is a very special section of New York City. It’s the largest and oldest remnant of old growth forest around, and it’s right here in the Bronx! It’s almost like a time machine that gives a faint glimpse of the past. Strolling through, it’s not hard to imagine the kind of environments Henry Hudson and the Lenape people walked through. (For more on this subject check out the WLC’s Welikia project, previously known as Manhatta)

An ongoing survey at The Garden hopes to shed some light, sometimes literally, on a resident of the forest often overlooked — the tiny salamander. In particular, the terrestrial redback salamander, Plethodon cinereus. These little guys are one of the key species in the ecology of the forest. According to one of the wildlife biologists conducting the survey (Michael McGraw from Applied Ecological Services) the Redback salamander is thought to be the most abundant form of biomass in some northern deciduous forests. In a suitable area, you may be able to see one “under any rock you flip.” That’s a lot of amphibians!

The survey consists of a series of “cover boards” spread out strategically across the forest. These boards are simply rubber mats that provide a nice, cool dark place that salamanders like to congregate under (much like densely packed leaf mass). These boards are periodically checked, with biologists taking note of the number, size and significant features of any salamanders they may find. It gets a little dirty and the salamanders are tiny, quick and extremely squirmy, but the biologists and a few volunteer citizen scientists braved through to successfully gather their data during their latest visit.

Check out a video of their work featuring Forest Manager Jessica Schuler after the jump!

Read More

Posted in Around the Garden, Science on November 12 2010, by Plant Talk

The New York Botanical Garden contains not just an amazing array of flora, it is also home to an amazing diversity of fauna. There are hawks and owls, Jose the beaver, squirrels of many colors, bunnies, tiny mice, various migrating birds, and I hear tell of a duet of turkeys (though I haven’t yet seen them for myself). But it is one of the Gardens smallest animals that was our attention a few weeks ago: salamanders.

The New York Botanical Garden contains not just an amazing array of flora, it is also home to an amazing diversity of fauna. There are hawks and owls, Jose the beaver, squirrels of many colors, bunnies, tiny mice, various migrating birds, and I hear tell of a duet of turkeys (though I haven’t yet seen them for myself). But it is one of the Gardens smallest animals that was our attention a few weeks ago: salamanders.

The Garden’s native Forest is home to two distinct populations of these small amphibians: Plethodon cinereus, the terrestrial Redback Salamander and Eurycea bislineata, the aquatic Northern Two-Lined Salamander.

Learn more about what salamander can teach us about the environment below.

Posted in Science on November 4 2010, by Plant Talk

Paying for Benefits Provided by Natural Systems May Help in Conservation

|

Scott A. Mori, Ph.D., Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany, has been studying New World rain forests for The New York Botanical Garden for over 35 years. He has witnessed an unrelenting reduction in the extent of the tropical forests he studies and as a result has become interested in the ecosystem services provided by them. |

|

Li Gao, a biology student at SUNY Binghamton, studied ecosystem services under the supervision of Dr. Mori as an intern at the Garden this past summer. |

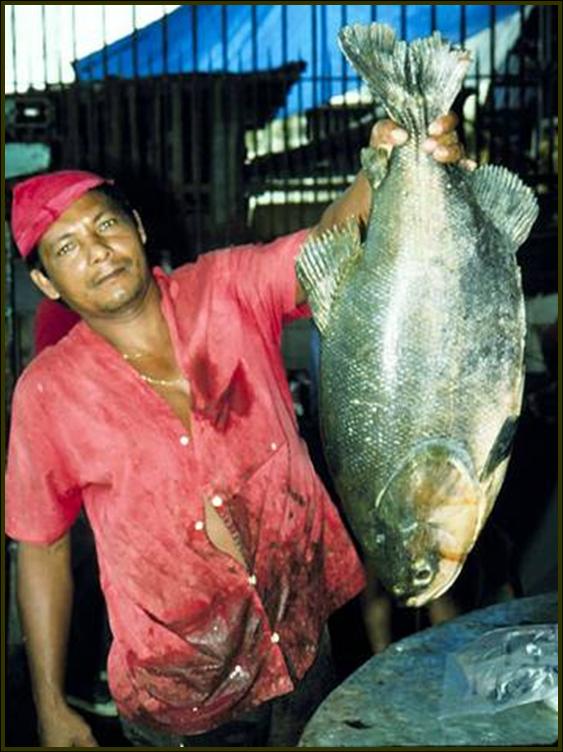

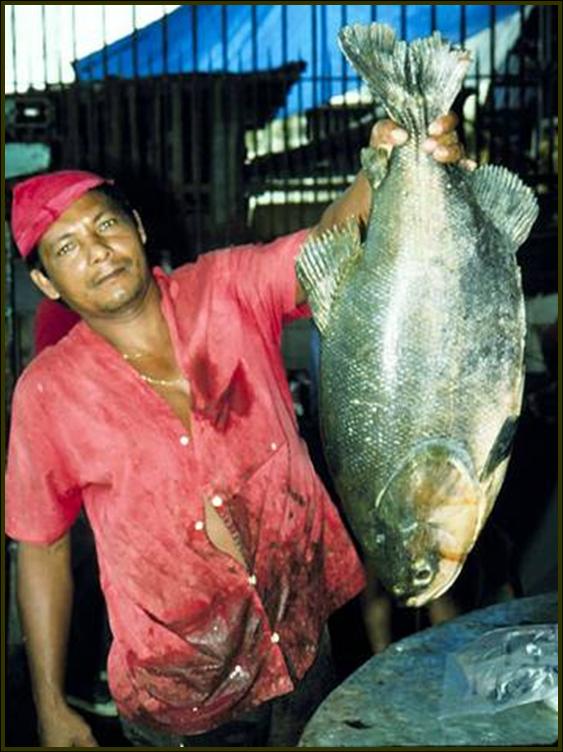

Photo by C. Gracie: Fish harvested from nature is an example of an ecosystem service.

For the past three years, the Institute of Systematic Botany of The New York Botanical Garden has been preparing an inventory of the plants of the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica. Our goal is to document the native plants growing on the Osa through collections and images, most of which are the result of the botanical explorations of Costa Rican botanist Reinaldo Aguilar. The Osa is the last large expanse of lowland rain forest along the Pacific coast of all of Mesoamerica, and is a place where jaguars, large flocks of scarlet macaws, nesting sea turtles, and over 2,000 species of plants (821 of which are trees) can still be seen in their natural habitat.

For the past three years, the Institute of Systematic Botany of The New York Botanical Garden has been preparing an inventory of the plants of the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica. Our goal is to document the native plants growing on the Osa through collections and images, most of which are the result of the botanical explorations of Costa Rican botanist Reinaldo Aguilar. The Osa is the last large expanse of lowland rain forest along the Pacific coast of all of Mesoamerica, and is a place where jaguars, large flocks of scarlet macaws, nesting sea turtles, and over 2,000 species of plants (821 of which are trees) can still be seen in their natural habitat.

Tropical forests boost local economies through the sale of tropical forest products like timber, chocolate, and Brazil nuts, but in the process of producing these products part of the original forest is modified, often harming the plants and animals that live there. Tropical forests, though, have value far beyond that derived from these obvious harvests. The fish found in their rivers and lakes and the animals living in their forests provide sources of protein for the local population. The rich diversity of plants and animals found in tropical forests as well as their scenic beauty make them a favorite destination for tourists. In addition, tropical forests are reservoirs of genetic diversity, play an important role in maintaining the stability of the world’s atmospheric gases, and help control hydrological cycles on local, regional, and global scales.

Read More

Posted in Science on October 28 2010, by Plant Talk

How Do Insects Feed on this Plant with Sticky White Latex?

|

Amy Berkov is an Honorary Research Associate with The New York Botanical Garden’s Institute of Systematic Botany; she studies interactions between wood-boring beetles and trees in the Brazil nut family. Photo of Amy Berkov by Chris Roddick. |

When I was in graduate school I decided to turn my East Village community garden plot over to the insects. I was an NYBG/CUNY Ph.D. candidate hoping to study plant-animal interactions. By happy accident I ended up in an entomology course at the American Museum of Natural History. The revelation that plants produce a huge variety of chemicals capable of manipulating insect behavior captured my imagination, so I planted six native species: three milkweeds (Asclepias) and three goldenrods (Solidago) to attract specific beetles.

When I was in graduate school I decided to turn my East Village community garden plot over to the insects. I was an NYBG/CUNY Ph.D. candidate hoping to study plant-animal interactions. By happy accident I ended up in an entomology course at the American Museum of Natural History. The revelation that plants produce a huge variety of chemicals capable of manipulating insect behavior captured my imagination, so I planted six native species: three milkweeds (Asclepias) and three goldenrods (Solidago) to attract specific beetles.

Fifteen years later, one goldenrod species is still hanging on, but common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) is clearly the winner—and it’s now making furtive advances into neighboring plots (the original plant probably spread by underground rhizomes). My observations have convinced me that the common milkweed is anything but common!

Fifteen years later, one goldenrod species is still hanging on, but common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) is clearly the winner—and it’s now making furtive advances into neighboring plots (the original plant probably spread by underground rhizomes). My observations have convinced me that the common milkweed is anything but common!

Plants in the genus Asclepias are called milkweeds because of the sticky white latex that pours out of wounded tissues. Asclepias latex is rich in toxic cardiac glycosides, and the scientific genus name comes from Asklepios, the ancient Greek physician.

Some milkweed-feeders actually sequester the toxins to defend themselves from predators, but how do they avoid getting their mouthparts hopelessly gummed up? Some slice right through leaf midribs, which diverts the latex flow and enables the “trencher” to feed downstream of the cut. For a video clip of the best-known trencher, the monarch caterpillar, click here.

Read More

Posted in Programs and Events, Science on October 26 2010, by Thomas Andres

| Thomas C. Andres is an Honorary Research Associate at the Garden. |

I am especially excited that three record-breaking pumpkins are on display this month at The New York Botanical Garden. The heaviest one is not only the heaviest fruit ever grown, but also the heaviest fruit in the plant kingdom! The scientific name of the species, Cucurbita maxima, says it all. How did this all come about?

First, I should explain my relationship with these plants. I work here at the Botanical Garden with Michael Nee on the taxonomy of the genus Cucurbita. This group of a little over a dozen species includes the squashes, pumpkins, and certain kinds of gourds. They all originally grew wild in the tropical and subtropical Americas. Five of the species were domesticated and represent some of our oldest New World crop plants. This means that Italy not only didn’t have tomatoes before Columbus, but no zucchini!

Wild Cucurbita fruit are like a baseball in size, shape, and even almost in hardness. This is quite large for a wild fruit, although nothing to write to the Guinness Book of World Records about. So how could a fruit that is so hard and so big travel around enough to form new populations? Wild Curcurbita do often grow in flood plains, and float during floods, but they would then only float in one direction: downstream.

A tale of megafauna, Columbus, selective breeding, and the pursuit of the one ton pumpkin. More below.

January 21, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Seno Brujo, Chile, 54° 30’S, 71° 32’W

January 21, 2011, Isla Grande de la Tierra del Fuego, Seno Brujo, Chile, 54° 30’S, 71° 32’W

The New York Botanical Garden

The New York Botanical Garden