Inside The New York Botanical Garden

Science

Posted in Science on December 29 2009, by Plant Talk

Part 3 in a 3-part series

Read Part 1 and Part 2

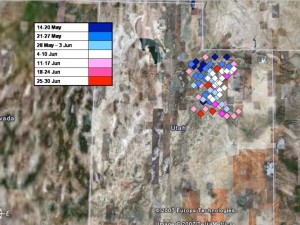

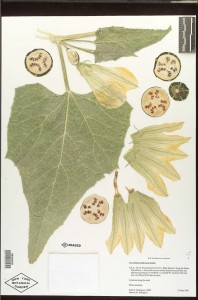

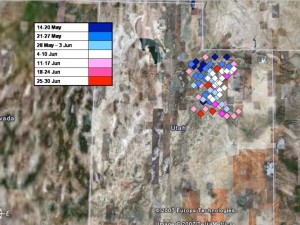

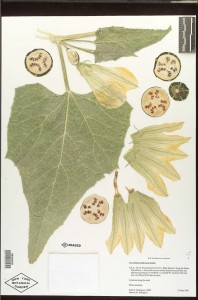

During the past 15 years, my staff and I have devoted a great deal of effort in the creation of the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium, which is an on-line catalog of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. Entries in the Virtual Herbarium are created by transcribing the data from the specimen label into an electronic database, and often capturing a digital image of the specimens as well.

During the past 15 years, my staff and I have devoted a great deal of effort in the creation of the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium, which is an on-line catalog of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. Entries in the Virtual Herbarium are created by transcribing the data from the specimen label into an electronic database, and often capturing a digital image of the specimens as well.

We have digitized just over 1 million of our 7.3 million specimens so far. Although we don’t know exactly what objective drives each of the 8,400 daily visits to the Virtual Herbarium, we deduce from reviewing the sources of these “hits” that most users are seeking basic biodiversity information.

Read More

Posted in Science on December 15 2009, by Plant Talk

Part 2 in a 3-part series

Read Part 1

Worldwide trends notwithstanding, the chief concern of our William and Lynda Steere Herbarium management team on a daily basis is not the decline in the use of natural history collections, as reported in a New York Times article this summer, but rather how to keep up with the needs of all our users.

Worldwide trends notwithstanding, the chief concern of our William and Lynda Steere Herbarium management team on a daily basis is not the decline in the use of natural history collections, as reported in a New York Times article this summer, but rather how to keep up with the needs of all our users.

Scientists use the Steere Herbarium to answer the most critical questions about plant diversity, namely: How many species are there? How are they related to one another? What environmental factors control their growth? Given that plants supply most of the food, fuel, shelter, and medicines for the earth’s population, predicting how these organisms may respond to climate change is one of the most pressing questions for scientists today.

Visitors are sometimes surprised that most of the scientists who use to the Herbarium are still doing the fundamental work of documenting the Earth’s biodiversity. “Don’t we know all the species yet?” some have asked. The answer is “No, not by a long shot.” Estimates are that we know only about 75 percent of the world’s plant species and less than 10 percent of the species of the fungi, the two major groups of organisms represented in the Herbarium collections.

Read More

Posted in Science on December 1 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Barbara Thiers, Ph.D., is Director of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium and oversees the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium. |

Part 1 in a 3-part series

The 7.3 million collections of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium, the largest in the Western Hemisphere and among the four largest in the world, form the core of a beehive of activity. On a typical work day during the past year, our Herbarium staff of 29 full-time equivalents answered 28 requests for information via e-mail or phone, helped 10 visiting researchers use the Herbarium, sent 214 specimens on loan (over the year we sent to 38 countries and 38 states of the United States), added 360 new specimens, and digitized 400 specimens for sharing on-line through the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium.

The 7.3 million collections of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium, the largest in the Western Hemisphere and among the four largest in the world, form the core of a beehive of activity. On a typical work day during the past year, our Herbarium staff of 29 full-time equivalents answered 28 requests for information via e-mail or phone, helped 10 visiting researchers use the Herbarium, sent 214 specimens on loan (over the year we sent to 38 countries and 38 states of the United States), added 360 new specimens, and digitized 400 specimens for sharing on-line through the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium.

Each herbarium specimen is a primary source of historical information about the Earth’s vegetation as well as about the person who collected it. The label that accompanies each specimen gives not only the name of the plant, but where and when it was collected, and by whom. Some labels give far more information, such as the name of the expedition, the funding source, and names of other members of the collecting party. Historical specimens often bear original handwriting, and sometimes notes, correspondence or sketches.

Read More

Posted in People, Science on November 17 2009, by Plant Talk

Staffer Discovers Home, Resting Place of NYBG Founders on Staten Island

|

Lisa Vargues is Curatorial Assistant of the Herbarium. |

In honor of the 150th birthday this year of Nathaniel Lord Britton (1859–1934), who with his wife, Elizabeth Gertrude Britton (1858–1934), founded The New York Botanical Garden, I set out to retrace some of his footsteps. My pursuit provided further insight into his life and brought some fascinating places to light.

In honor of the 150th birthday this year of Nathaniel Lord Britton (1859–1934), who with his wife, Elizabeth Gertrude Britton (1858–1934), founded The New York Botanical Garden, I set out to retrace some of his footsteps. My pursuit provided further insight into his life and brought some fascinating places to light.

This spark of nostalgic curiosity came over me ever since I started working on the Flora Borinqueña Digital Herbarium and Library, a project that makes available online the unpublished manuscript of the popular flora of Puerto Rico— along with images of related specimens—that Britton was working on at the time of his death.

After more than 70 years, Britton’s final manuscript emerged from storage, and in a Rip van Winkle moment has been resurrected in a brand new era of computers and digitization. Ironically, Britton was resistant to installing electricity (“an unnecessary luxury”) in the Garden’s Museum building (now the Library building), and instead frugally worked by gaslight, according to The New York Botanical Garden: An Illustrated Chronicle of Plants and People.

While transcribing some of Britton’s last written words in the Flora Borinqueña, including his shaky handwritten marginal notes, I wondered where the Brittons’ final resting place is and whether there are any remnants of their life here in New York, outside of the Garden.

And so my search began.

Read More

Posted in Learning Experiences, Science on October 22 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Susan Fraser is Director of the LuEsther T. Mertz Library. |

Paradigm shifts have altered the way knowledge is communicated—from the written word to the printed word and now to the digital word. The proliferation of electronic resources and rapid changes in technology require increased flexibility in how libraries acquire and disseminate knowledge. One remarkable example is the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL), a consortium of natural history libraries that are digitizing and making freely available the world’s literature on biodiversity. Collectively, the 12-member consortium holds most of the recorded knowledge of the natural world, over 2 million volumes.

Paradigm shifts have altered the way knowledge is communicated—from the written word to the printed word and now to the digital word. The proliferation of electronic resources and rapid changes in technology require increased flexibility in how libraries acquire and disseminate knowledge. One remarkable example is the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL), a consortium of natural history libraries that are digitizing and making freely available the world’s literature on biodiversity. Collectively, the 12-member consortium holds most of the recorded knowledge of the natural world, over 2 million volumes.

The Botanical Garden is a founding member of the BHL, which began in 2006 and is expanding to include a BHL Europe and partners in China and Australia. It has rapidly become an international sensation.

The project saves immense hours of research time for both information seekers and library staff. The Mertz Library research staff can now refer to the BHL portal to fill interlibrary loan requests or research inquires. Previously, staff would photocopy pages of books or journal articles upon request. Now, if a scientist in South Africa needs to reference The Grasses and Grasslands of South Africa (1918) for instance, she can do so on her own and from her own computer.

By cooperating in this multi-institutional effort, BHL members can perform bulk digitization with limited risk of duplication, lack of standardization, or loss of intellectual integrity while providing a huge amount of biodiversity material online. To date, the Mertz Library has scanned over 6,000 volumes amounting to over 3 million pages. The BHL portal currently contains almost 15,000 titles and 16 million pages, and it continues to grow.

Read More

Posted in Programs and Events, Science on October 1 2009, by Plant Talk

NYBG Hosts Free Presentation on the History of Amateur Mycology

|

Brian M. Boom, Ph.D., is President of the Torrey Botanical Society and Director of the Caribbean Biodiversity Program at The New York Botanical Garden.

|

Founded in 1867 in New York City, the Torrey Botanical Society is the oldest botanical association in the Americas. Throughout its long, distinguished history of promoting interest in botany and in disseminating information about all aspects of plants and fungi, among the most important of the Society’s activities is its lecture series. Each year, a lecture is presented in October, November, December, March, April, and May, and the schedule is posted through the Society’s Web site. The lectures are free and open to the public. Refreshments precede each lecture.

The first Torrey lecture of this season is on Tuesday, October 6, at 6:30 p.m. in the Arthur and Janet Ross Lecture Hall at The New York Botanical Garden. David W. Rose, archivist, writer, and past president of the Connecticut-Westchester Mycological Association, will present Great Goddess of Decay! A History of Amateur Mycology in the United States. You can read his abstract online.

In addition to hosting the lecture series, the Society publishes a scholarly journal (The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society), organizes numerous field trips to local sites of botanical and mycological interest, and offers a series of grants and awards to support field work and seminars. I invite you to come to the October 6 lecture and to meet fellow plant and fungi enthusiasts.

Posted in Science, Wildlife on September 24 2009, by Plant Talk

Cricket Crawl at the Garden Confirms Presence of These—and More

|

Jessica Arcate is Manager of the Forest.

|

|

Robert Naczi, Ph.D., is Curator of North American Botany.

|

On the evening of Saturday, September 12, a fearless group of five naturalists outfitted with headlamps and recording equipment, ventured throughout the Botanical Garden to listen for seven species of crickets and katydids for the NYC Cricket Crawl.

On the evening of Saturday, September 12, a fearless group of five naturalists outfitted with headlamps and recording equipment, ventured throughout the Botanical Garden to listen for seven species of crickets and katydids for the NYC Cricket Crawl.

We were inspired to do the count, arranged by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and others, after reading about the mystery of the “missing katydid of New York City.” It seems that in 1920, local naturalist William T. Davis reported the possible disappearance of the Common True Katydid (pictured here, Photo by ©MusicofNature.org) from Staten Island. Present-day experts on katydids and crickets surmised that katydids might be like the fabled canary in a coal mine, lost to environmental toxins, and so decided to organize the survey. Several species are common in the region and call at night with sounds easy to distinguish, permitting an observer to list the species present in an area just by listening to them. The Cricket Crawl promised to reveal patterns of biodiversity relevant to such matters as climate change, effects of deforestation, and adaptations of wildlife to urban areas.

Actually, we wondered why all the fuss about katydids? We knew we had them here at The New York Botanical Garden. As part of the efforts to document the natural history of NYBG, Edgardo Rivera and Robert Naczi had been studying insects at NYBG since mid-July. Because many insects find ultraviolet light (“black light”) irresistible, nocturnal collecting with a black light can be a very productive way of surveying local insect diversity. Edgardo and Rob had heard Common True Katydids at NYBG on several occasions, but came to realize their significance after reading announcements about the Cricket Crawl.

And so a team was assembled (see photo by Tom Andres) to confirm the identities of these insects for the Cricket Crawl: Edgardo Rivera (Senior Curatorial Assistant), Tom Andres (Herbarium volunteer), Kendrick Simmons (independent videographer), Jim Schuler (volunteer), and Jessica Arcate (Manager of the Forest). The evening began in the Perennial Garden and Ladies’ Border, and then headed to the knolls of the Arthur and Janet Ross Conifer Arboretum. At these sites four species were heard: Jumping Bush Cricket, Field Cricket, Greater Anglewing, and Common True Katydid. At the Mitsubishi Wetlands the fifth and last species of the night was added to the list, the Oblong-winged Katydid. Next, the team trekked into the center of the Forest. To our surprise one of the great horned owls from the Garden’s resident family was calling. The owl called several times from different trees, and it was incredible to hear. (To hear the sound of a great horned owl, click here.)

And so a team was assembled (see photo by Tom Andres) to confirm the identities of these insects for the Cricket Crawl: Edgardo Rivera (Senior Curatorial Assistant), Tom Andres (Herbarium volunteer), Kendrick Simmons (independent videographer), Jim Schuler (volunteer), and Jessica Arcate (Manager of the Forest). The evening began in the Perennial Garden and Ladies’ Border, and then headed to the knolls of the Arthur and Janet Ross Conifer Arboretum. At these sites four species were heard: Jumping Bush Cricket, Field Cricket, Greater Anglewing, and Common True Katydid. At the Mitsubishi Wetlands the fifth and last species of the night was added to the list, the Oblong-winged Katydid. Next, the team trekked into the center of the Forest. To our surprise one of the great horned owls from the Garden’s resident family was calling. The owl called several times from different trees, and it was incredible to hear. (To hear the sound of a great horned owl, click here.)

Read More

Posted in Science on September 15 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Scott A. Mori, Ph.D., Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany, has been studying New World rain forests for The New York Botanical Garden for over 30 years. Over the course of his career, Dr. Mori has witnessed an unrelenting reduction in the extent of the tropical forests he studies. |

On August 22, an image showing a small green patch of forest in the midst of a treeless area prepared for soybean cultivation appeared on the front page of The New York Times. The accompanying article explained that the fertile soils underlying forests in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil, are suitable for supporting large soybean plantations. As evidence of the magnitude of the forest destruction, the author noted that an increasing demand for Brazilian soybeans led to the conversion of 700 square miles of forest to soybean fields in that state during the last five months of 2007 alone!

On August 22, an image showing a small green patch of forest in the midst of a treeless area prepared for soybean cultivation appeared on the front page of The New York Times. The accompanying article explained that the fertile soils underlying forests in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil, are suitable for supporting large soybean plantations. As evidence of the magnitude of the forest destruction, the author noted that an increasing demand for Brazilian soybeans led to the conversion of 700 square miles of forest to soybean fields in that state during the last five months of 2007 alone!

The future of plant and animal diversity in Latin American forests depends on an understanding of how fragile the plant/animal interactions of tropical ecosystems are and the role human consumption plays in altering natural ecosystems. The relationships between plants and animals in the tropics are so closely co-evolved that man’s utilization of tropical forests almost always results in some loss of biodiversity. Soybean cultivation is an extreme example, because in this agricultural system soybeans entirely displace the plants and animals that formerly occupied the destroyed forests.

Trees remaining after forest destruction such as the Brazil nut tree above, photographed by W. W. Thomas, do not effectively reproduce. While this tree and others like it may still live for many years, they no longer produce the next generation of trees because the forest conditions needed for the pollination of their flowers, the dispersal of their seeds, and the growth of their seedlings into adult trees no longer exist.

Read More

Posted in Exhibitions, Science, The Edible Garden on September 7 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Valerie Imbruce, Ph.D., Professor and Director of Environmental Studies at Bennington College in Vermont who was a doctoral student at the Botanical Garden, researches the production and distribution of ethnic fruits and vegetables for New York City markets. She will be holding an informal conversation about ethnic fruits and vegetables in Chinatown and urban food systems during Café Scientifique on September 12 as part of The Edible Garden. |

Cities, home to half of the world’s growing population, are poised to redefine how we produce and supply our food. Cities are where people are demanding more farmers markets and community supported agriculture groups and where there is a local agriculture craze. Food is a social movement with a particularly urban flavor.

Cities, home to half of the world’s growing population, are poised to redefine how we produce and supply our food. Cities are where people are demanding more farmers markets and community supported agriculture groups and where there is a local agriculture craze. Food is a social movement with a particularly urban flavor.

Living in southern Vermont for the past year after being in New York for nearly a decade, I learned that in New York City it is easier to purchase a diet of regionally produced foods than in the food-producing regions themselves because of the structure of our food supply chains.

Since World War II the number of farms in the United States had been declining, but between 2002 and 2007, the last year for which data were available, there was a 4 percent increase. According to the U.S. Census of Agriculture, these new farms are half the size of the average U.S. farm, have younger operators, and have sales of which one product accounts for no more than 50% of the farm income. These are the types of farms, small and diversified run by a new generation of farmers, which farmers markets, community supported agriculture, and chef-farm partnerships have been the primary supporters of.

But direct marketing arrangements are not enough to support a sustained increase in farm numbers: The volume of food sold directly from farm to consumer is a drop in the bucket compared with the volume of food that is sold through wholesale distribution. Why should New York, the second largest apple producing state in the nation, export its apples and then turn around and import apples from Chile and New Zealand for New Yorkers to eat? Why should the United States export more than 4,000 tons of yogurt and then import just over the same volume? It’s because fundamental aspects of the “mainstream” food system make it difficult for regional farmers to access their regional urban markets. We need to get commodity agriculture and supermarkets on board to change this, and we need city government to create policies to ensure access to urban markets by regional farmers.

Read More

Posted in Exhibitions, Science, The Edible Garden on September 2 2009, by Plant Talk

NYBG Student Travels to Asia to Trace Eggplant’s Roots

|

Rachel Meyer, a doctoral candidate at the Botanical Garden, specializes in the study of the eggplant’s domestication history and the diversity of culinary and health-beneficial qualities among heirloom eggplant varieties. She will hold informal conversations about her work at The Edible Garden‘s Café Scientifique on September 13. |

The eggplant (Solanum spp.) may not seem like the world’s most exciting food crop at first thought, but its history and diversity are actually quite intriguing. The common name, “eggplant,” actually covers more than one species, whose size, shape, color, and flavor are remarkably different throughout the world.

The eggplant (Solanum spp.) may not seem like the world’s most exciting food crop at first thought, but its history and diversity are actually quite intriguing. The common name, “eggplant,” actually covers more than one species, whose size, shape, color, and flavor are remarkably different throughout the world.

People have grown eggplants for over 2,000 years in Asia, and it is thought that eggplants were used as medicine before being selected over time to become a food. Many present-day cultivars of eggplants still contain medicinally potent chemical compounds, including antioxidant, aromatic, and antihypertensive, some of which might be the same compounds responsible for flavor as well.

If we can unravel the history of the eggplant’s domestication and investigate the health-beneficial and gastronomic qualities of heirloom eggplant varieties, we can promote specific varieties that may be useful to small-scale farmers, practitioners of alternative medicine, and eggplant lovers around the world.

I spent seven weeks in China and the Philippines last winter exploring how different ethnic groups use local eggplant varieties. These regions in Asia are important, because scientists are still not sure where eggplants were first domesticated (that is, selected by people over generations for desirable qualities instead of just harvested from the wild). We know it was in tropical Asia, but the written record doesn’t go back far enough to provide more clues. For that reason I also collected wild relatives of eggplant that might be the ancestor of the domesticated crop.

Read More

During the past 15 years, my staff and I have devoted a great deal of effort in the creation of the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium, which is an on-line catalog of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. Entries in the Virtual Herbarium are created by transcribing the data from the specimen label into an electronic database, and often capturing a digital image of the specimens as well.

During the past 15 years, my staff and I have devoted a great deal of effort in the creation of the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium, which is an on-line catalog of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. Entries in the Virtual Herbarium are created by transcribing the data from the specimen label into an electronic database, and often capturing a digital image of the specimens as well.

The eggplant (Solanum spp.) may not seem like the world’s most exciting food crop at first thought, but its history and diversity are actually quite intriguing. The common name, “eggplant,” actually covers more than one species, whose size, shape, color, and flavor are remarkably different throughout the world.

The eggplant (Solanum spp.) may not seem like the world’s most exciting food crop at first thought, but its history and diversity are actually quite intriguing. The common name, “eggplant,” actually covers more than one species, whose size, shape, color, and flavor are remarkably different throughout the world.