Inside The New York Botanical Garden

Science

Posted in Science on August 26 2009, by Plant Talk

Scientists have extended the barcode of life to plants, a development that will have far reaching impacts in the years ahead.

Earlier this month, an international consortium of plant scientists achieved a milestone when they published the results of a multi-year analysis selecting two regions of DNA to serve as barcodes for the identification of plants. The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The goal of using a standard segment of a gene as a unique identifier of all living organisms has worked better for animals than for plants, as a gene from the mitochondrial genome, cytochrome oxidase I or COI, is sufficiently different among animal species to allow unique identification of 95% of species. Since this gene is not highly variable in plants, 52 scientists from 24 institutions in nine countries have worked for several years to identify genetic sequences that can routinely be sequenced without ambiguous results and that differ enough to allow discrimination of species. The group selected two genes from the chloroplast genome, rbcL and matK, which together total about 1,450 base pairs.

Agreement on these barcode genes will pave the way to building the reference database necessary to assign barcode sequences to species. The use of barcodes will have tremendously broad impact both in the research community and also with many practical applications. Barcode sequences have in numerous instances helped identify species new to science and improve our understanding of diversity in the natural world. But more importantly it will enable plants that could formerly be identified only by increasingly rare experts with specific plant families to be identified by technicians, enabling broad ecological surveys. At a more practical level, it will support the identification of fragmentary plant materials in poison control centers and in other forensic applications, and allow accurate identification of ingredients in food and dietary supplements.

An ambitious effort to assemble barcodes for all of the trees of the world is being coordinated by The New York Botanical Garden, and it will ultimately facilitate better monitoring of the world timber trade. This international partnership will take years to complete its goal, but in the short term, enough sequence data has been collected already to identify the family to which most plants belong, and in many cases the genus as well. Timber harvesters will be much less likely to cut endangered timber species if they know that this technology may allow buyers to identify these species and refuse to accept and pay for them. Ultimately, barcoding will affect our lives in many ways by providing a method for the identification of the millions of species that inhabit our planet.

Please help support important botanical research such as this that is integral to the mission of The New York Botanical Garden.

Posted in Exhibitions, Science, The Edible Garden on August 25 2009, by Plant Talk

|

John Mitchell is a Research Fellow with the Institute of Systematic Botany at The New York Botanical Garden, where he also chairs the Library Committee. He studies the cashew family (Anacardiaceae) worldwide. |

The cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale), a native of Brazil, is the source of cashew nuts and the cashew apple. Wild cashew trees occur in the savannas and some coastal forests in northern South America, Brazil, and adjacent Bolivia and Paraguay. Portuguese colonists introduced the cashew from Brazil to their colonies in India and Africa in the late 1500s. Today cashew is cultivated throughout the lowland tropics of the world. The majority of people who live in the tropics use the cashew tree primarily for its cashew apple rather than for the seed (which you know as the cashew nut).

The cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale), a native of Brazil, is the source of cashew nuts and the cashew apple. Wild cashew trees occur in the savannas and some coastal forests in northern South America, Brazil, and adjacent Bolivia and Paraguay. Portuguese colonists introduced the cashew from Brazil to their colonies in India and Africa in the late 1500s. Today cashew is cultivated throughout the lowland tropics of the world. The majority of people who live in the tropics use the cashew tree primarily for its cashew apple rather than for the seed (which you know as the cashew nut).

The seed is enclosed in a brown to gray fruit, often called the cashew nutshell, which contains a dermatitis-causing poisonous resin. This resin is chemically similar to that found in poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), to which the cashew is closely related; they are both members of the same family (Anacardiaceae) along with other commercial crops, including pistachio, pink peppercorn, and mango.

Cashew nuts are roasted or eaten raw after careful separation from the poisonous shell (fruit); chemicals in the nutshell liquid are extracted to produce adhesives, lubricants, solvents, plastics, and antimicrobials. Brake linings of cars and particleboard are two products partially derived from cashew nutshell chemicals. Cashews are also used to make cashew butter, or as an ingredient in cakes, cookies, and candies. Large-scale commercial cashew production is done in Brazil, tropical Africa, India, and Southeast Asia.

The cashew apple is a pear-shaped juicy structure that subtends the fruit and is actually the swollen flower/fruit stalk (pedicel) called a hypocarp. (Above is a photo of an immature cashew fruit and hypocarp developing on a tree, taken by Susan K. Pell, BBG.) The cashew apple can be candied or its juice fermented to make wine or spirits, or it can be used as an ice cream flavoring. The “apple” attracts dispersers such as fruit bats, coatis (relatives of raccoons), monkeys, lizards, and various fruit-eating birds who discard the poisonous fruit and consume the cashew apple.

My apprenticeship with Garden senior curator Dr. Scott Mori in the early 1980s resulted in the publication of a monograph, The Cashew and Its Relatives (Anacardium: Anacardiaceae), published by NYBG Press. The cashew genus, Anacardium, was originally described by Linnaeus and includes 11 species native to South and Central America.

Please help support important botanical research such as this that is integral to the mission of The New York Botanical Garden.

Posted in Science on August 20 2009, by Plant Talk

Garden Scientist Studies “Culturally Keystone Species”

|

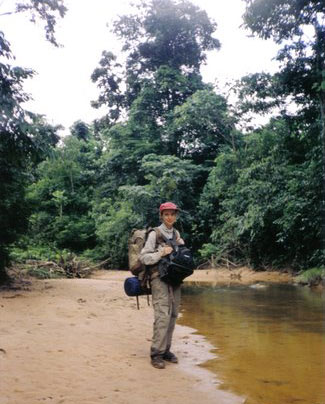

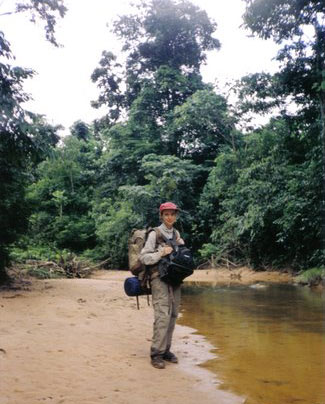

Brian M. Boom, Ph.D., is Director of the Caribbean Biodiversity Program at The New York Botanical Garden.

|

Add one more item to the long list of threats that indigenous peoples around the world have to their cultural survival: global warming.

In the past, when the climate changed, indigenous groups could usually migrate to areas where the climate was suitable for their ways of life. Now, with indigenous groups often restricted to territories that are surrounded by farms, ranches, and settlements of more populous and powerful non-indigenous peoples, there is usually no where for them to go. They must endure the climatic changes by adapting; if they cannot adapt, their cultures may become extinct.

In the past, when the climate changed, indigenous groups could usually migrate to areas where the climate was suitable for their ways of life. Now, with indigenous groups often restricted to territories that are surrounded by farms, ranches, and settlements of more populous and powerful non-indigenous peoples, there is usually no where for them to go. They must endure the climatic changes by adapting; if they cannot adapt, their cultures may become extinct.

While the general problem of climate change to indigenous groups is global, it is also occurring in the Amazon, an area I have studied. A recent New York Times article reported that a drier, hotter Amazonia due to deforestation and climate change is killing off the fauna and flora that indigenous groups of the region depend on for their survival. And I have some data that bear on elucidating the gravity of this issue.

In the 1980s, I teamed up with fellow botanist Ghillean Prance and anthropologists William Balée and Robert Carneiro on a comparative ethnobotanical project with the goal of quantifying the use of trees by four indigenous Amazonian groups. We published the results of our studies in 1987 in the journal Conservation Biology (vol. 1, no. 4) under the title “Quantitative Ethnobotany and the Case for Conservation in Amazonia.” Our main general finding was that these groups had specific cultural uses for between about 50% to more than 75% of the tree species in their territories. This result illustrates just how tightly dependent native Amazonians are on their environment for cultural survival.

Read More

Posted in Science on August 13 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Scott A. Mori, Ph.D., Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany, has been studying New World rain forests for The New York Botanical Garden for over 30 years. This evening from 6 to 9 p.m., as part of the Edible Evenings series of The Edible Garden, he will hold informal conversations about chocolate, Brazil nuts, and cashews—some of his research topics—during Café Scientifique. |

The Brazil nut is known to most people as the largest nut in a can of mixed party nuts, but other than that, most people know little about it, including that it comes from an Amazonian rain forest tree of the same name or that it is really a seed, not a nut.

The Brazil nut was first discovered by Alexander von Humboldt and Aime Bonpland on the Orinoco River in Venezuela and made known to the scientific world as Bertholletia excelsa in1808. The generic name honors a famous French chemist and friend of Humboldt’s and excelsa refers to the majestic growth form of the tree. Although discovered in Venezuela, this species became known as the Brazil nut because Brazil was, and still is, a major exporter of the seeds.

For the past 35 years my research has focused on the classification and ecology of species of the Brazil nut family. The Brazil nut itself is only one of what I estimate to be about 250 species of that family found in the forests of Central and South America. This number includes nearly 50 species that do not have scientific names, mostly because collectors are usually not willing to climb into tall trees to gather the specimens needed to document their existence. My research on the Brazil nut family has taken me on many expeditions to the rain forests of the New World, and what I have learned about this family of trees can be found on The Lecythidaceae Pages.

The Brazil nut flower is large, roughly two inches in diameter, and fleshy, and the male part of the flower has a structure not found in any other plant family in the world. (See illustration at right by Bobbi Angell.) The fertile stamens are arranged in a ring that surrounds the style at the summit of the ovary. This ring has a prolongation on one side that is expanded at the apex to form a hood-like structure. At the apex of the hood are appendages that turn in toward the interior of the flower.

The Brazil nut flower is large, roughly two inches in diameter, and fleshy, and the male part of the flower has a structure not found in any other plant family in the world. (See illustration at right by Bobbi Angell.) The fertile stamens are arranged in a ring that surrounds the style at the summit of the ovary. This ring has a prolongation on one side that is expanded at the apex to form a hood-like structure. At the apex of the hood are appendages that turn in toward the interior of the flower.

A small amount of nectar is produced at the bases of these appendages. The fleshy “hood” presses directly onto the summit of the ovary and the six petals form an overlapping “cup” that blocks entry to the flower to all but the co-evolved pollinators.

The Brazil nut is known to be pollinated only by large bees with enough strength to lift up the hood and enter the flower. These bees are presumably rewarded for their efforts by the nectar they collect from the interior of the hood. When the bees are in the flower, pollen rubs off onto their heads and backs from where it is transferred to the stigma of subsequent flowers visited.

Read More

Posted in People, Science on August 6 2009, by Plant Talk

Promotes Dialogue between Traditional and Western Medicine Practitioners

|

Ina Vandebroek, Ph.D., is a Research Associate and Project Director of Dominican Traditional Medicine for Urban Community Health with the Botanical Garden’s Institute of Economic Botany. She has also conducted research on the medicinal uses of plants for community healthcare in Bolivia since 2000. Photo of Ina by Bert de Leenheer

|

Bolivia is a landlocked country in Latin America with a high level of biocultural diversity. The Andean mountains that run through the country from northwest to southeast give rise to 23 distinct ecological zones, ranging from the high plains (altiplano) at 13,123 feet, to lowland Amazon rain forest at less than 1,000 feet. The total number of plant species found in Bolivia is still unknown, but estimates are around 20,000. More than 30 distinct indigenous languages are spoken in the country—a reflection of its high ethnic diversity.

Bolivia is a landlocked country in Latin America with a high level of biocultural diversity. The Andean mountains that run through the country from northwest to southeast give rise to 23 distinct ecological zones, ranging from the high plains (altiplano) at 13,123 feet, to lowland Amazon rain forest at less than 1,000 feet. The total number of plant species found in Bolivia is still unknown, but estimates are around 20,000. More than 30 distinct indigenous languages are spoken in the country—a reflection of its high ethnic diversity.

Ever since I first set foot on Bolivian soil, I became enamored with the country’s cultures and traditions. Bolivia, or la llajta (home) as the Quechua people who make up one-third of its population would say, is where you eat roasted cow heart with peanut sauce (anticuchos), pay a ritual tribute to Mother Earth (la Pachamama) each first Friday of the month, or negotiate a good price with vendors at the largest open-air market in Latin America. The market, called La Cancha in the city of Cochabamba, is where you can find nearly anything you dream of. My favorite corner is where the dry and fresh herbs are as well as seeds, incense, llama fetuses (used for spiritual purposes), and mesas or ritual preparations for Mother Earth.

The Bolivian lowlands are home to several indigenous groups, many of whom do not have easy access to biomedical healthcare. This means that, all too often, traditional medicine is the only healthcare available. The crushing reality is that in life-threatening situations such as a hemophilic newborn, a venomous snakebite, or a serious gallbladder infection—all to which I have been a powerless witness—people die without reaching a hospital. Luckily, for many other illnesses, traditional healers are able to play a secure role in maintaining overall community health. Being indigenous community members themselves, healers’ role in healthcare is pivotal. Patients trust them and share with them the same cultural beliefs about the causes and treatment of illnesses.

Last month I began organizing indigenous community health workshops in Bolivia with the objective of promoting dialogue between biomedical healthcare providers and traditional healers about frequently occurring health problems. The idea is for the two groups to reach consensus about the best ways for traditional healers to deal with these conditions in communities without access to biomedical healthcare.

Read More

Posted in Exhibitions, Science, The Edible Garden on July 30 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Scott A. Mori, Ph.D., Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany, has been studying New World rain forests at The New York Botanical Garden for over 30 years. As part of The Edible Garden, he will hold informal conversations about chocolate, Brazil nuts, and cashews—some of his research topics—during Café Scientifique on August 13. |

The chocolate that we eat and drink is one of the most complicated foods utilized by mankind. Not only did it co-evolve in the rain forests of the New World with still unidentified pollinators and with the help of animals that disperse its seeds, but it also undergoes an amazing transformation when it is processed, going from inedible, bitter seeds to the delicious chocolate products that most of us enjoy.

The chocolate that we eat and drink is one of the most complicated foods utilized by mankind. Not only did it co-evolve in the rain forests of the New World with still unidentified pollinators and with the help of animals that disperse its seeds, but it also undergoes an amazing transformation when it is processed, going from inedible, bitter seeds to the delicious chocolate products that most of us enjoy.

I became fascinated with the natural history and cultivation of chocolate while working for the Cocoa Research Institute in southern Bahia, Brazil, from 1978 to 1980. I directed a program of plant exploration in what was then, botanically, one of the least explored regions of the New World tropics. During those two years, I made 4,500 botanical collections, including many species new to science and many from cocoa plantations.

The scientific name of the chocolate tree is Theobroma cacao L. Theobroma means “food-of-the-gods” in Greek; cacao is derived from the Aztec common name chocolatl; and “L.” is the abbreviation for Linnaeus, the botanist who coined the scientific name of the chocolate tree. The genus Theobroma includes 22 species.

One of the unsolved mysteries of the natural history of chocolate trees is its pollinators. Most varieties of chocolate are self-incompatible, which means that pollination of the flowers of a given plant with pollen from the same plant does not yield fruit. There are, however, some varieties that are self-compatible—the single tree growing in the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory at NYBG is proof, because it sets fruit. Nevertheless, for most chocolate trees to produce fruit, pollen has to be moved from one tree to the next. This does not happen frequently in plantations, because the average tree produces between just 20 and 40 fruits each year from the thousands of flowers that open on the tree.

Thus, a limiting factor in the production of chocolate is successful pollination, and because this has economic implications there has been considerable research about how to increase the production of chocolate by enhancing pollination. Some researchers believe midges (minute, mosquito-like flies) are the pollinators of chocolate trees. But the complexity and relatively large size of chocolate flowers in comparison to the size of midges indicates that they might be occasional visitors rather than the true or only pollinators of chocolate.

Read More

Posted in Programs and Events, Science on July 14 2009, by Plant Talk

The edible squashes have been a staple food in the Western Hemisphere for more than 5,000 years. The Aztecs and Mayas, as well as the Native Americans who met the Pilgrims, depended upon the squashes as one of the “three sisters” (corn, beans, squash) of early agriculture in the Americas.

The edible squashes have been a staple food in the Western Hemisphere for more than 5,000 years. The Aztecs and Mayas, as well as the Native Americans who met the Pilgrims, depended upon the squashes as one of the “three sisters” (corn, beans, squash) of early agriculture in the Americas.

Though squashes come in an amazing variety—from tender summer zucchini to hearty acorn squash and pumpkins—their great diversity comprises only five species: Cucurbita argyrosperma, Cucurbita ficifolia, Cucurbita maxima, Cucurbita moschata, and Cucurbita pepo. (Bottle gourds, thought by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus to belong to Cucurbita, are now placed in a separate genus, Lagenaria. They are useful for a variety of utensils and handicrafts, although not as good for eating.)

The domesticated species of Cucurbita were all derived from different wild ancestors—wild species that have survived droughts, pests, and diseases without care from people. Although the wild ancestors bear small, hard, bitter fruits, they are very valuable for breeding disease resistance into modern food plants.

Thomas Andres, co-founder of The Cucurbit Network and an Honorary Research Associate at the Botanical Garden, has worked for 30 years with Garden scientist Michael Nee, Ph.D., on squash research. Andres will present a Gallery Talk in the Britton Science Rotunda and Gallery on Friday, July 17, at 2 p.m. about his beloved topic. Following his talk is a behind-the-scenes tour of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium to see how scientists identify and classify plants and to view some specimens of squashes and their relatives.

Space is limited, please call 718-817-8703 for reservations.

Posted in People, Science on July 8 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Wayne Law, Ph.D., is a Postdoctoral Research Associate who studies ecology, ethnobotany, and conservation in Micronesia. Come speak with him at our Café Scientifique on July 9, from 6 to 8 p.m., in the Conservatory Courtyard as part of The Edible Garden. |

When someone asks you to visualize a banana, most people in the United States will picture the typical, slightly curved, yellow-skinned banana with a bland white flesh that can be found at local grocery stores. However, a number of different varieties exist: small bananas, straight bananas, red-skinned bananas, creamy-tasting bananas—even bananas that have a bright-orange flesh—and many of these varieties can be found on tiny islands in the Pacific known as Micronesia, where Botanical Garden scientists are conducting research.

When someone asks you to visualize a banana, most people in the United States will picture the typical, slightly curved, yellow-skinned banana with a bland white flesh that can be found at local grocery stores. However, a number of different varieties exist: small bananas, straight bananas, red-skinned bananas, creamy-tasting bananas—even bananas that have a bright-orange flesh—and many of these varieties can be found on tiny islands in the Pacific known as Micronesia, where Botanical Garden scientists are conducting research.

One of our goals in Micronesia is to record traditional plant knowledge that is the foundation of these islands’ unique cultures. The plant knowledge throughout this region is incredibly diverse as plants are integral to all aspects of daily island life, from the construction of houses and canoes to use as medicines and foods. As traditional ways of life are influenced by modern amenities, we are constantly seeing evidence that traditional plant knowledge is being lost and that many common items once made from nature are being replaced by plastic products that have an origin thousands of miles away. One study we conducted analyzed the knowledge of food plant varieties in Kosrae, the easternmost island of the Micronesia chain.

By the early 1900s, Kosrae, an island home to 7,000 people in the Eastern part of Micronesia, had already been exposed to French and Russian explorers, whalers, beachcombers, pirates, and traders, beginning the erosion of what had been a very traditional Pacific island lifestyle. At that time, Ernst Sarfet, a German ethnographer, documented much of Kosrae’s cultural aspects and plant uses during the Hamburg South Seas expedition, an impressive voyage that lasted two years and produced a 13-volume publication based on the observations made during the expedition. The translated work provides an early record of the different varieties of bananas, breadfruit, coconuts, pandanus, sugar cane, soft and hard taro, and yams. (The photo shows a display of some of the fruits and vegetables mentioned, during a holiday celebration in Kosrae.)

Read More

Posted in People, Science on June 23 2009, by Plant Talk

Garden Scientist Participates in the Venice Biennale

|

Ina Vandebroek, Ph.D., is a Research Associate and Project Director of Dominican Traditional Medicine for Urban Community Health with the Botanical Garden’s Institute of Economic Botany. Photo of Ina by Bert de Leenheer |

Every two years, Venice turns into the Cannes of the art world for La Biennale di Venezia: an international festival of art—with a capital “A.” From June to November, this city that always counts more visitors than residents becomes the scene for everything and everyone involved in the arts: curators, art critics, collectors, art aficionados, and, of course, the artists themselves. This year I participated as an ethnobotanist who collaborated with the Belgian contemporary artist Jef Geys for the 53rd Biennale, called Fare Mundi (Making Worlds).

Every two years, Venice turns into the Cannes of the art world for La Biennale di Venezia: an international festival of art—with a capital “A.” From June to November, this city that always counts more visitors than residents becomes the scene for everything and everyone involved in the arts: curators, art critics, collectors, art aficionados, and, of course, the artists themselves. This year I participated as an ethnobotanist who collaborated with the Belgian contemporary artist Jef Geys for the 53rd Biennale, called Fare Mundi (Making Worlds).

You might wonder what an ethnobotanist has to do with art? I usually spend most of my days in the field with my nose stuck in plants, collecting them to make botanical specimens and identify their Latin names. Or, I conduct interviews with people to find out how these plants are used by local cultures, such as in traditional medicines. But now I found myself flying to the city of gondolas and vaporettos (water taxis) to assist in the inauguration of the Belgian pavilion where the installation from Jef Geys is on display.

When I was 13 years old and still living in Belgium, Jef was my art teacher. I remember making conventional drawings in art class, but Jef was by no means a conventional art teacher. He likes to challenge his surroundings and the people in it, and by doing so subtly makes them change their perceptions about art and life. He offers no lessons; instead, the experience itself is the lesson. Now, so many years later, I relived that experience when Jef asked me to apply the methods I had acquired during my training as an ethnobotanist at The New York Botanical Garden to “go out in the urban fields of New York City and collect 12 plants growing in the streets of my home in the Bronx that could be used as medicines by homeless people.” Jef asked other acquaintances from the art world who live in Moscow, Brussels, and Villeurbanne (France) to do the same thing and guided them with the methodology.

Read More

Posted in NYBG in the News, Science, Shop/Book Reviews on June 11 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Stephen Sinon is Head of Information Services and Archives in The New York Botanical Garden’s LuEsther T. Mertz Library. |

The Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries (CBHL), of which NYBG is a founding member, recently presented its 10th Annual Literature Awards. The awards, created to recognize significant contributions to the literature of botany and horticulture, honored three exceptional books this year, all of which acknowledge input from The New York Botanical Garden and all of which can be found in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library. The council is the leading professional organization in the field of botanical and horticultural information services.

The Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries (CBHL), of which NYBG is a founding member, recently presented its 10th Annual Literature Awards. The awards, created to recognize significant contributions to the literature of botany and horticulture, honored three exceptional books this year, all of which acknowledge input from The New York Botanical Garden and all of which can be found in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library. The council is the leading professional organization in the field of botanical and horticultural information services.

The General Interest category was topped by Fruits and Plains: The Horticultural Transformation of America, by Philip J. Pauly. (This title is available at Shop in the Garden.) Genera Palmarum: the Evolution and Classification of Palms, by John Dransfield, Natalie W. Uhl, Conny B. Asmussen, William J. Baker, Madeline M. Harley, and Carl E. Lewis, won the Technical category.

In celebration of the 10th anniversary of the awards, a Special Recognition Award was presented to TL-2, more formally known as Taxonomic Literature: a Selective Guide to Botanical Publications and Collections with Dates, Commentaries and Types, 2nd edition. This monumental work, the first edition of which was compiled by Frans A. Stafleu and Richard S. Cowan as a seven-volume set completed in 1988, is one of the most important resources in botanical literature. The current edition was updated by Laurence J. Dorr, Erik A. Mennega, and Dan H. Nicolson and was honored by CBHL for significant contributions to the literature of botany and the study of plants.

In celebration of the 10th anniversary of the awards, a Special Recognition Award was presented to TL-2, more formally known as Taxonomic Literature: a Selective Guide to Botanical Publications and Collections with Dates, Commentaries and Types, 2nd edition. This monumental work, the first edition of which was compiled by Frans A. Stafleu and Richard S. Cowan as a seven-volume set completed in 1988, is one of the most important resources in botanical literature. The current edition was updated by Laurence J. Dorr, Erik A. Mennega, and Dan H. Nicolson and was honored by CBHL for significant contributions to the literature of botany and the study of plants.

In compiling the massive 15-volume reference work, the authors of Taxonomic Literature used the collections of the Mertz Library; now, over 800 linear feet of their original research papers are in the Library’s archives. The CBHL award was given in recognition of the release of the final volume in this set.

TL-2 acknowledges the outstanding collections of the Mertz Library as well as the assistance provided by the staff, as does Fruits and Plains, whose author also consulted the collection several times while working on his book. The third work, Genera Palmarum, acknowledges the valuable input of two New York Botanical Garden Science staff members: palm expert and Institute of Systematic Botany curator Andrew Henderson, Ph.D., and postdoctoral research associate Thomas Couvreur, Ph.D.