Inside The New York Botanical Garden

herbarium

Posted in Science on December 15 2009, by Plant Talk

Part 2 in a 3-part series

Read Part 1

Worldwide trends notwithstanding, the chief concern of our William and Lynda Steere Herbarium management team on a daily basis is not the decline in the use of natural history collections, as reported in a New York Times article this summer, but rather how to keep up with the needs of all our users.

Worldwide trends notwithstanding, the chief concern of our William and Lynda Steere Herbarium management team on a daily basis is not the decline in the use of natural history collections, as reported in a New York Times article this summer, but rather how to keep up with the needs of all our users.

Scientists use the Steere Herbarium to answer the most critical questions about plant diversity, namely: How many species are there? How are they related to one another? What environmental factors control their growth? Given that plants supply most of the food, fuel, shelter, and medicines for the earth’s population, predicting how these organisms may respond to climate change is one of the most pressing questions for scientists today.

Visitors are sometimes surprised that most of the scientists who use to the Herbarium are still doing the fundamental work of documenting the Earth’s biodiversity. “Don’t we know all the species yet?” some have asked. The answer is “No, not by a long shot.” Estimates are that we know only about 75 percent of the world’s plant species and less than 10 percent of the species of the fungi, the two major groups of organisms represented in the Herbarium collections.

Read More

Posted in Learning Experiences, Science on April 9 2009, by Plant Talk

|

Nieve Shere is Information and Collections Manager for The New York Botanical Garden’s Institute of Economic Botany. |

As the Information and Collections manager for the Institute of Economic Botany (IEB), I manage ethnobotanical data and collections, coordinate the work of volunteers, and curate the Teaching Herbarium of Economic Plants, a valuable tool for education and botanical science.

As the Information and Collections manager for the Institute of Economic Botany (IEB), I manage ethnobotanical data and collections, coordinate the work of volunteers, and curate the Teaching Herbarium of Economic Plants, a valuable tool for education and botanical science.

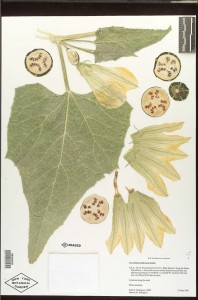

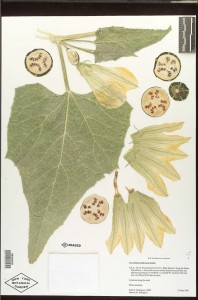

The Teaching Herbarium comprises specimens that have economic value—for instance, those that are used in a commercial industry such as food production—and that are preserved in a way that allow for hands-on study. In fact, the Teaching Herbarium is used to train students in botanical identification as well as in the development of the Botanical Garden’s educational curricula and scientific exhibitions.

The Herbarium’s first specimens, in the early 1980s, were collected by Garden scientists Michael Balick, Ph.D., and Hans Beck, Ph.D., shortly after the creation of the IEB; later collections included those by Garden scientist Scott Mori, Ph.D., and longtime volunteer Dick Rauh, Ph.D. The majority of the teaching specimens are from the Arts Resources for Teachers and Students (ARTs) project, the first project initiated by IEB to develop the Teaching Herbarium.

Through the ARTs project, middle and elementary school kids on the Lower East Side surveyed plants sold in the Chinese and Hispanic markets. The students collected vegetables such as bok choy, cabbage, and taro and pressed, dried, and mounted the specimens. The specimens documented the historic and commercial data specifically about the diversity of foods sold in New York City markets. These collections, along with the specimens collected by the above-mentioned scientists, were instrumental in the development of the early Economic Botany courses that Dr. Balick taught at Yale University and at Columbia University’s CERC program.

Over the years the collection has continued to grow into a rich repository of plants used commercially such as for food, construction, and medicine. It now houses more than 600 specimens made up of 200 species from 113 different families. Dedicated volunteers reorganize and repair damaged specimens and update the database, making the collection even more user-friendly. The IEB is fortunate to have had for more than 25 years the dedication of Dr. Rauh, who has carefully assisted in the curation of this collection with the help of volunteers Connie Papoulas, Margaret Comsky, Ermgaard Clinger, Gwen Dexter, and Daniel Kulakowski.

Specimens from Dr. Mori’s Brazilian teaching collection are currently on display in the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory (pictured) as part of The Orchid Show: Brazilian Modern. Additional specimens from the Teaching Herbarium will be featured and new plant material provided for visitors to make their own specimens during the Herbarium Specimen-Making Workshops to be held in the Library building each day from April 9 to 19, beginning at 2 p.m.

If you would like to get involved with the Teaching Herbarium, please contact Volunteer Services at 718.817.8564 or volunteer@nybg.org.

Posted in People, Science on April 1 2009, by Plant Talk

Where Plants Live Forever

|

Amanda Gordon is a freelance writer based in New York City. |

The displays in The Orchid Show: Brazilian Modern include specimens of orchids and other plants from Brazil that are stored in the Botanical Garden’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. The fourth largest herbarium in the world and the largest in the Western Hemisphere, it contains more than 7 million specimens of plants and fungi.

The displays in The Orchid Show: Brazilian Modern include specimens of orchids and other plants from Brazil that are stored in the Botanical Garden’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. The fourth largest herbarium in the world and the largest in the Western Hemisphere, it contains more than 7 million specimens of plants and fungi.

So how does the Herbarium work, and how do scientists use it? To find out, I sat down with Dr. Barbara Thiers, Director of the Steere Herbarium and the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium. A plant scientist specializing in liverworts, Barbara belongs to a botanical family: Her father was a botanist who ran a herbarium, and her husband, Dr. Roy Halling, is also a scientist at the Garden, focusing on mushrooms.

What is the history of herbariums?

The concept of the herbarium originated in 14th- or 15th-century Italy. Plants were collected because people figured out early on that plants could be useful in treating maladies. Reference collections were made so people would know what plant to use for what. At first the plants were kept in bundles. Then someone got the idea of pressing the plants and putting them in books. The plants are then mounted on paper. That’s how specimens are preserved to this day.

Where are the specimens stored?

It’s amazing the amount of design that goes into making a good herbarium cabinet. The specimens are kept in specially designed steel cases with good sealing gaskets that keep them flat and dry and dark and away from bugs. If they’re well maintained, they can last indefinitely.

How do scientists use the specimens in the Steere Herbarium?

There’s a lot of use by people who are documenting rare and endangered species. Others are using the data for ecological modeling so they can ask questions about how the vegetation will change and how fast temperatures will rise in order to identify areas that are endangered or that are critical habitats for animals. A user could be curious about particular groups of plants—for example, forest species that are used for timber.

We have a number of herbarium sheets that are the “first-known collections” of specimens, such as purple loosestrife and cheat grass. The sheets can help to date the invasion of a species and to understand how a plant may have moved across a country. Government agencies are also heavy users—for example, the folks at Kennedy Airport. When they confiscate plant material, they’re supposed to do the best job they can to identify the material.

Do these records become obsolete?

No. Just the opposite: The specimen in the herbarium is how you save it forever after. Even when you have a very high-resolution digital image, there are some things you can only examine by looking at the actual specimen. This is the best information on what plants grew where and when.

You’ve already digitized 1.7 million specimens since 1995. What are your objectives for online access?

We have to do our best to handle all the material and make it as available for scientific research as possible. Our goal is to digitize the whole Steere Herbarium and to constantly improve the way we do it. Electronically, we’ll take some big leaps in how we share our data online. Wherever possible, we are linking the information about the specimens to the research that’s been done here by our staff and to the library collections. We’re creating a portal to the research that’s been done here.

How much use does the Steere Herbarium get?

People who come here to look at the specimens total 1,200 days spent here each year. We also send out 40,000 to 50,000 specimens a year for people to borrow. We send and receive 350 specimens a day in our shipping office.

Can amateur botanists use the Steere Herbarium or the Starr Virtual Herbarium?

We don’t have a lot of content that interprets what we have for a general audience, but we have some evidence that general audiences use it. We get a lot of hits by state and educational Web sites. We have dried specimens, so someone has to be able to look at a dried plant and imagine what it looks like. To look up a specimen you have to know the scientific name.

Do you get a chance to enjoy the living collections at the Botanical Garden?

I really love the Rock Garden, and one of my favorite places is Azalea Way. I like them not because they’re beautiful to look at, which they are, but because I have a great fondness for the plants that grow in those spots.

Please help support the important botanical research, education, and programs that are integral to the mission of The New York Botanical Garden.

Worldwide trends notwithstanding, the chief concern of our William and Lynda Steere Herbarium management team on a daily basis is not the decline in the use of natural history collections, as reported in a New York Times article this summer, but rather how to keep up with the needs of all our users.

Worldwide trends notwithstanding, the chief concern of our William and Lynda Steere Herbarium management team on a daily basis is not the decline in the use of natural history collections, as reported in a New York Times article this summer, but rather how to keep up with the needs of all our users.