In Search of Thomas Edison’s Botanical Treasures

Posted in Applied Science on October 30, 2013 by Lisa Vargues

Lisa Vargues is a Curatorial Assistant at the New York Botanical Garden’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. Her work includes digitizing plant specimens for the C. V. Starr Virtual Herbarium, with a focus on the West Indies, the Amazon Basin, and historical specimens from the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

The quiet corridors of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium here at The New York Botanical Garden are lined with steel cabinets where preserved plant specimens are stored for scientific study, but they are also a treasure trove of history, filled with stories waiting to be told.

One of those stories came to light recently when I set out to determine whether any traces remained in the Steere Herbarium of a significant but little-known research project that involved one of America’s most famous inventors—Thomas Alva Edison.

In the late 1920s, Edison was on a quest for plants that could be grown locally, quickly, and economically to produce latex and provide America with a domestic source of rubber. At the time, the country was dependent on imported rubber for such important products as automobile tires, and Edison and his friends Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone were concerned that an international crisis such as a war could cut off that supply. In 1927, they formed the Edison Botanic Research Corporation in Fort Myers, Florida, and Edison enlisted crews to collect plant specimens throughout the United States, particularly in the South.

Edison’s quest brought him to the Botanical Garden to conduct botanical research in collaboration with the Garden’s Head Curator, John Kunkel Small. At one point the inventor who perfected the light bulb even had a small laboratory in the grand Beaux-Arts building that now houses The LuEsther T. Mertz Library. Tests concluded that the goldenrod (in the plant genus Solidago) contained the most promising amount of latex.

More than eight decades later, Herbarium Director Barbara Thiers, Ph.D., had a question: were any of Edison’s plant specimens or other research materials still preserved somewhere in the Steere Herbarium?

My question was: where should I begin my search? Edison had tested over 17,000 plants. Before me were four floors with 7.3 million pressed and filed specimens, including our massive Solidago collection, which fills 569 shelves. An online search provided a few clues, including references to his namesake goldenrod, Solidago edisoniana, plus a 1935 Journal of Agricultural Research article listing ten Solidago species tested in Fort Myers.

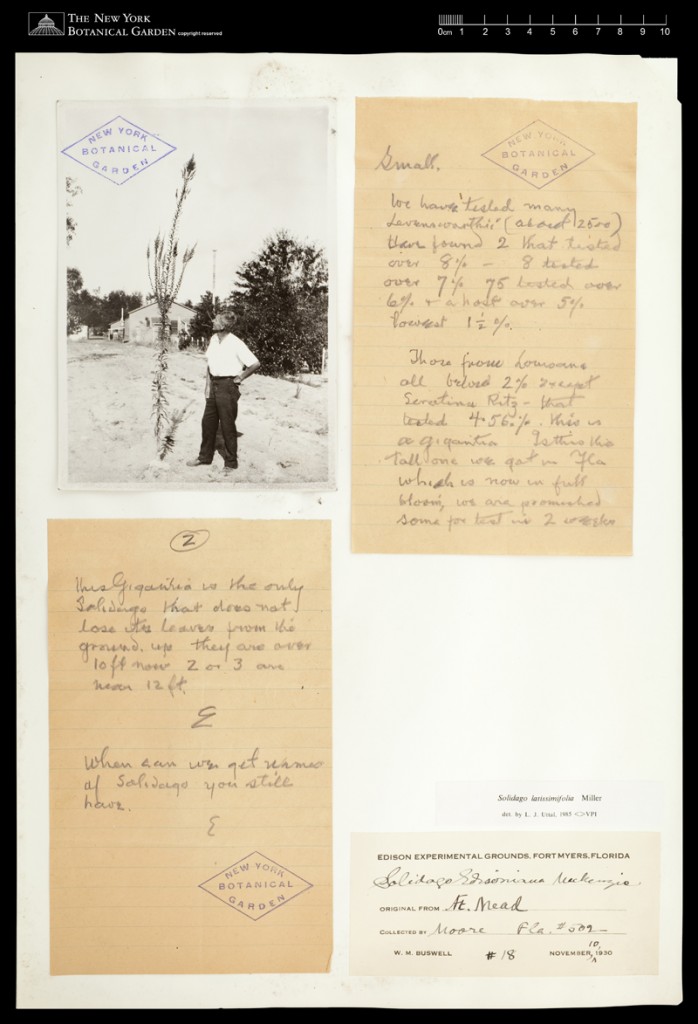

Guided by these clues and carefully searching through Herbarium cabinets, I followed the trail of Solidago species. Halfway through the list, I pulled out a folder labeled Solidago elliottii, a synonym for Solidago edisoniana. Sorting through the contents, my eyes suddenly fell upon a yellowed letter, handwritten in pencil. It was initialed “E” in two places. Was it a letter from Edison? I hurried to check online samples of Edison’s handwriting, and there was no doubt. It had been written by Thomas Edison himself.

Addressing the Head Curator simply as “Small,” Edison’s undated letter discusses Solidago species and percentages of extracted rubber. A 1930 S. edisoniana label had been mounted next to it along with a photo taken in Fort Myers of a towering goldenrod. The folder contained additional treasures: a pressed S. edisoniana specimen, more photos, notes by W. M. Buswell (a Florida botanist and assistant to Edison), and slides.

I continued to search the Solidago collection and spotted a 1927 S. gigantea specimen labeled “Edison Botanic Research Corporation,” collected by Joseph Nelson Rose, a botanist hired by Edison to collect plants in Texas and Mexico. This one specimen led to 20 more Edison specimens, filed in six plant families.

It was now clear: Edison had left his mark throughout the Herbarium. But, for me, the most exciting and meaningful discovery was Edison’s letter—a testament to his meticulous attention to detail and unwavering enthusiasm about his research projects. Remarkably, the letter had apparently remained unread and undisturbed in the Herbarium for more than 80 years.

After Edison’s death in 1931, the U. S. Department of Agriculture resumed the search for a domestic latex source, but the project ended when synthetic rubber was developed during World War II. At the Herbarium, the search for Edison material has since uncovered more specimens, and the hunt will undoubtedly continue. Where to search next has yet to be decided, and what might be found is unknown. Perhaps the best thing to do is to follow Thomas Edison’s own advice: “When you have exhausted all possibilities, remember this—you haven’t.”

Congratulations to you Lisa. Article well written. I know you feel so proud. Good for you. Hope you get broad recognition.