Legume Legacy: Bringing a World-Renowned Scientist’s Work to a New Generation

Posted in Interesting Plant Stories on November 20, 2013 by Jacquelyn Kallunki

Jacquelyn Kallunki, Ph.D., is Associate Director and Curator of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. She and Garden colleagues Benjamin Torke, Ph.D., and Melissa Tulig were the principal researchers involved in creating the Barneby Legume Catalogue.

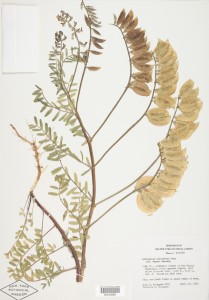

A recently completed online catalogue of plant specimens in the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium highlights the scientific work of a world-renowned expert on the bean and pea family whose long and colorful career was spent largely at The New York Botanical Garden.

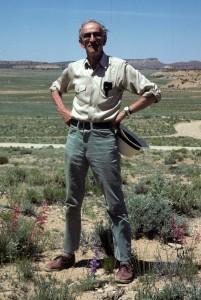

A self-taught botanist, Dr. Rupert C. Barneby (1911-2000) spent 57 years at the Botanical Garden, publishing almost 8,000 pages of scientific papers and describing 1,250 plants new to science. Based on his observations and measurements of specimens in the Steere Herbarium, he differentiated species and annotated the specimens with accurate names.

English by birth, Dr. Barneby made regular field trips to the American West and other destinations to collect plants, accompanied by his partner, Dwight Ripley, an American whom he met while attending Harrow, the prestigious English school. In the 1940s and 1950s, he and Ripley were friends and early patrons of Jackson Pollock and other Abstract Expressionist painters, as well as such literary lights as W. H. Auden and Aldous Huxley.

Among the plants in the legume family that fascinated Dr. Barneby were the “locoweeds,” species of the “milkvetch” genus Astragalus that are toxic to cattle and other grazing animals. They are widespread in the Western United States and cause significant economic losses to ranchers. Depending on the species, these plants can poison in three ways; those causing the disease “locoism” do so by action of the alkaloid Swainsonine, which causes abnormal neurologic behavior and heart failure.

Many species in the plant groups that he studied are rare and often threatened. In Astragalus alone, 20 species are on the federal endangered species list. Dr. Barneby corresponded with dozens of staff members of national and state parks in the West who were charged with developing conservation plans for rare species in those parks. He not only identified plant specimens and photographs that were sent to him, but also provided ecological observations and suggestions for other places to search for the plants.

Taken as a whole, Dr. Barneby’s work in descriptive plant systematics was unsurpassed in the 20th century. That work is now readily available online through the new Barneby Legume Catalogue, which includes the 81,000 specimens in the Steere Herbarium on which his research was based.

The information in the specimen labels, specimen images, identification keys, and illustrations from Dr. Barneby’s published work will be useful to a new generation of range managers seeking to identify poisonous species of “locoweeds” and to conservationists trying to save rare species from extinction.

To learn more about Dr. Barneby’s life and work, you can find an online biography here.

This blog describes two major accomplishments. The first is the description of one of the most productive botanical careers of all time, that of Rupert Barneby. The second is making Rupert’s contributions available online to all those interested in legumes, one of the most species rich and economically important groups of flowering plants. Many of the questions asked by those studying legumes can now be answered by consulting the NYBG website instead of making an expensive trip to The New York Botanical Garden.

Imagine a legume specialist working in Brazil trying to identify an unknown specimen of a legume in a group that Rupert studied. Now that researcher has Rupert’s publications available online and is able to compare images of the specimens Rupert identified with his or her identifications! Thanks to this effort, Rupert’s legacy is now easily available for current and future legume specialists to use and to build upon.

My congratulations to Jackie Kallunki and her team for this major accomplishment and to the National Science Foundation for making this project possible.