An Unwanted Hug

Posted in Interesting Plant Stories on January 22, 2014 by Scott Mori

Scott A. Mori, Ph.D., is the Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany at The New York Botanical Garden. His research centers on plants of the New World tropics.

Normally, the term “tree hugger” brings to mind an environmental activist who takes action to protect trees from destruction by other humans. In contrast, the plant shown here is a tree hugger that may hasten the death of the tree it embraces. The plant “hugging” the tree is a fig, one of the nearly 700 species of the genus Ficus of the mulberry family (Moraeae).

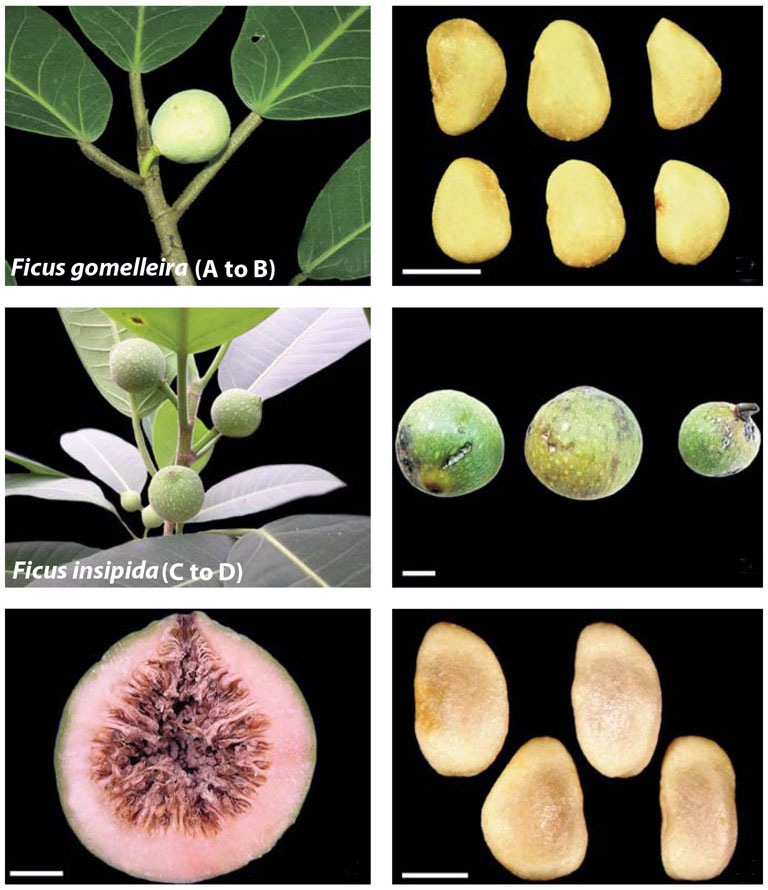

Many species of Ficus are “keystone” species, meaning they play an especially large role in their ecosystems. Their fruits—figs—are eaten by a wide variety of animals, especially species of birds and bats. Bird figs are usually red (Fig. 2) because birds are attracted by red, and bat figs are usually green at maturity because bats often find their food by echolocation and aroma, not by color (Fig. 3).

Figs that embrace trees like this are called strangler figs, but this is a misnomer. They do not strangle the host plant. They do, however, harm their hosts by robbing them of light, water, and nutrients.

The life cycle of a strangler fig starts with the dispersal of its seeds. For example, a bat plucks a fig and carries it to a night roost, where it eats the fruit. As the fig passes through the digestive track of the bat, the pulp is digested, but the seeds remain intact.

When the bat defecates, usually while in flight, the seeds are expelled and often stick to a tree, which then serves as the host to the fig plant. The seed germinates, a seedling is formed, and the plant grows both upward toward the crown of the host and downward toward the ground.

As the Ficus continues to grow, it begins to compete with the host plant for light—fig leaves shade those of the host—and the fig’s roots absorb water and nutrients that would have been used by the host. The fig’s host is not strangled, but it is outcompeted for what it needs to grow.

Scott, can you clarify Figure 3. I assume what I would label as boxes b and f are the seeds? Do the seeds in f belong to the fruit in e? They seem mighty big if one compares the scale bars.