Hanging Out in the Rain Forest

Posted in Location Shots from the Field on March 10, 2014 by Scott Mori

Scott A. Mori, Ph.D., is the Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany at The New York Botanical Garden. His research interests are the ecology, classification, and conservation of tropical rain forest trees.

This winter’s severe cold and abundant snow have led me to recall the hundreds of comfortable nights I have spent sleeping in a hammock in a rain forest as part of my expeditions to collect plant specimens for the NYBG’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium.

The hammock, an invention of Amazonian Indians, is the most practical way to sleep in the rain forest. Although it took me a while to get used to sleeping in a hammock, I now look forward to climbing into one after a long day of collecting and preparing plant specimens. The most comfortable hammocks are the traditional ones made of cotton, but the lightest are called garimpeiro hammocks, using the Portuguese word for prospectors or miners because Brazilian gold miners favor them. Made of synthetic fiber, they weigh less than a pound. In combination with a mosquito net and a large backpacking tarp, the garimpeiro hammock is ideal for trips requiring long hikes in the forest.

If weight is not a concern, then a larger and more comfortable cotton hammock weighing about three pounds can be used. Some first-time visitors to rain forests anticipate that it will be so hot that they won’t need blankets at night. They are unpleasantly surprised when the temperature drops in the early morning hours and it becomes difficult to sleep because of the cold. A summer sleeping bag that can be unzipped as needed guarantees a good night’s sleep.

The first rule in hammock-sleeping is to take a shower (or a dip in a nearby river or pond) and scrub vigorously to remove insects and arachnids, especially ticks, which could turn a comfortable night’s sleep into a nightmare. A cardinal sin is to recline in another person’s hammock in dirty field cloths, introducing insects into a clean hammock.

Inexperienced hammock-sleepers sometimes turn over and flip out when they first try to lie down on the hammock, or they crash to the ground due to improperly tied knots. Thus, rule two is to get into the hammock by slowly adding your weight to make sure the hammock ropes are properly tied.

The third rule is to position oneself at an angle rather than parallel to the length of the hammock. That makes your body more or less flat and not arched. I also find that a small camping pillow adds a lot to my comfort.

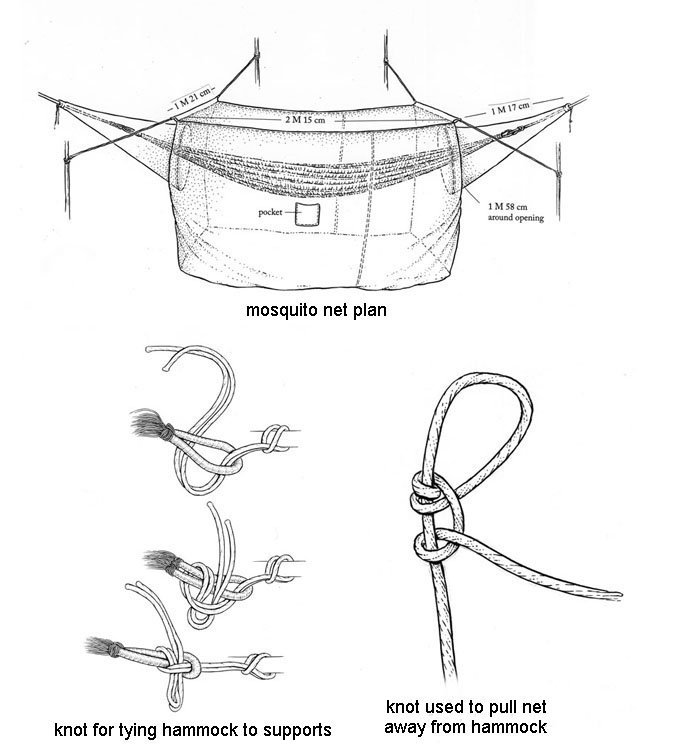

Finally, a fine-meshed mosquito net is essential to keep out insects and stop vampire bats from sucking blood from exposed body parts (see accompanying illustration).

Clean, warm, dry, and protected from insects, one can enjoy the sights and sounds of the forest—the approaching green and yellow lights of different fireflies, the hauntingly beautiful middle-of-the night song of the common potoo, the early morning roaring of howler monkeys, the dawn whooping of the blue-crowned motmot, and the raucous early morning chatter of chachalacas. Forest sounds, however, can make it almost impossible for some neophytes to sleep. One of my expedition participants was so irritated by the croaking of frogs that he left his hammock in the middle of the night and made a futile attempt to silence a frog in the gutter of the shelter he was sleeping under. Another, who had chosen to sleep in the forest away from the main camp, was terrified by the calls of howler monkeys because he mistakenly believed they were the roars of jaguars.

Whether you are an aspiring tropical botanist or just plan on taking an ecotour to the tropics, I hope these tips add to your rain forest adventure and help you sleep as comfortably as I have for the many nights I have been fortunate to spend there.

For more tips about visiting rain forests, see Chapter Three of Dr. Mori’s book Tropical Plant Collecting: From the Field to the Internet.