An Unusual Find in the Herbarium: A Story of Righting a Past Wrong

Posted in Past and Present on December 5, 2014 by Sarah Dutton

Sarah Dutton is a project coordinator who is currently working to digitize the algae collection in the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium at The New York Botanical Garden.

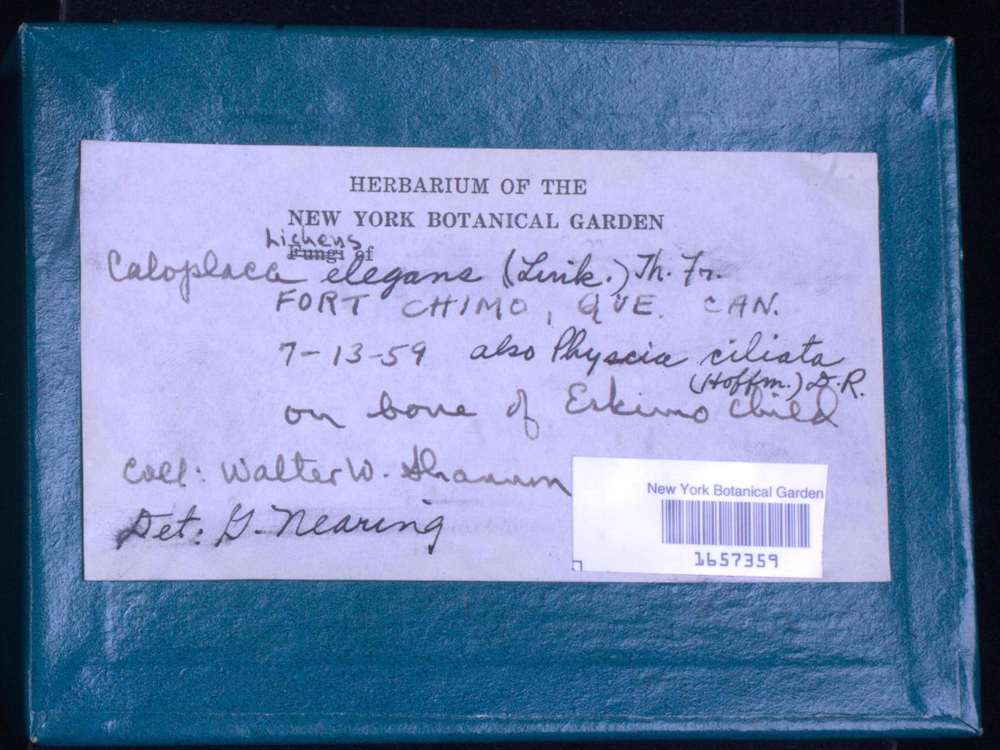

While making high-resolution digital images of lichen-covered rocks that are part of the collection in the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium, I came across a specimen not long ago with an unusual and rather alarming label. Plainly written as part of the collection data on this otherwise inconspicuous box was the statement that the specimen was “on bone of Eskimo child.” I opened the box to find, indeed, a bone of some kind with bright orange and yellow lichen growing on it.

I happen to have studied anthropology in college. One of the most important things you learn in a modern anthropology class is that many of the interactions between researchers and indigenous peoples during the long history of the discipline were downright exploitative and unethical by today’s standards. For example, archaeologists and anthropologists have had an unfortunate history of taking artifacts and even human remains from groups of people without consent from the members of that community—and sometimes even when they were explicitly asked not to. Today, many indigenous peoples are working to repatriate these artifacts and human remains back to their original communities. This possible human bone in the Steere Herbarium immediately concerned me, and I wondered whether the NYBG should attempt to return it to the people it came from. Dr. Barbara Thiers, the Garden’s Vice President for Science Adminstration, agreed that we should look into it, and we began to investigate the history of the specimen.

First, we analyzed the label. It seemed to have been written in two distinct hands: that of Walter W. Shannon, the collector, who wrote that the specimen was found in “Fort Chimo, Que. Can.” on July 13, 1959, “on bone of Eskimo child,” and that of Guy Nearing, a well-known botanist who determined the specimen to contain Caloplaca elegans and Physcia ciliata. To learn more about the history of the specimen, we attempted to research Shannon and his collection trip, but no records about a Walter Shannon who had a connection with the Garden could be found. Because the lichens on the bone were visually striking but actually quite common, Dr.Thiers suggested that Shannon might not have been a botanist. Instead, he could have been an amateur who had picked up the specimen on a trip to Fort Chimo—a town in far northern Quebec, now called Kuujjuaq—that he had made for other reasons.

(Photo © Orbitale, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

With the help of Louis Gagnon, the Director of the Department of Museology at the Avataq Cultural Institute in northern Quebec, we were able to send the remain to Canada for further investigation. There, archaeologists confirmed that the bone was human, and arrangements were made to return the remain for reburial by the Nunavimmiut, the Inuit people of the vast region in northern Quebec known as Nunavik. Mr. Gagnon said that Robert Fréchette, the cultural institute’s Director General, handed the remain over to the mayor of Kuujjuaq, Tunu Napartuk. Mayor Napartuk wrote that he plans to “make sure that the proper burial is completed with the help of the Anglican Church. It will be suggested that the human remain be brought back to Old Fort-Chimo (which is located across the river) as it seems the most likely place it was taken from.” Louis Gagnon informed us that the Nunavimmiut have been working to repatriate all of the human remains that were taken from them over the years. Though ours was a relatively small repatriation, I am happy that our effort was meaningful to them.