Ellen Hutchins: Ireland’s First Female Botanist

Posted in Nuggets from the Archives on January 2, 2015 by Sarah Dutton

Sarah Dutton is a project coordinator in the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium, where she is working on a project to digitize the Steere Herbarium’s collection of algae.

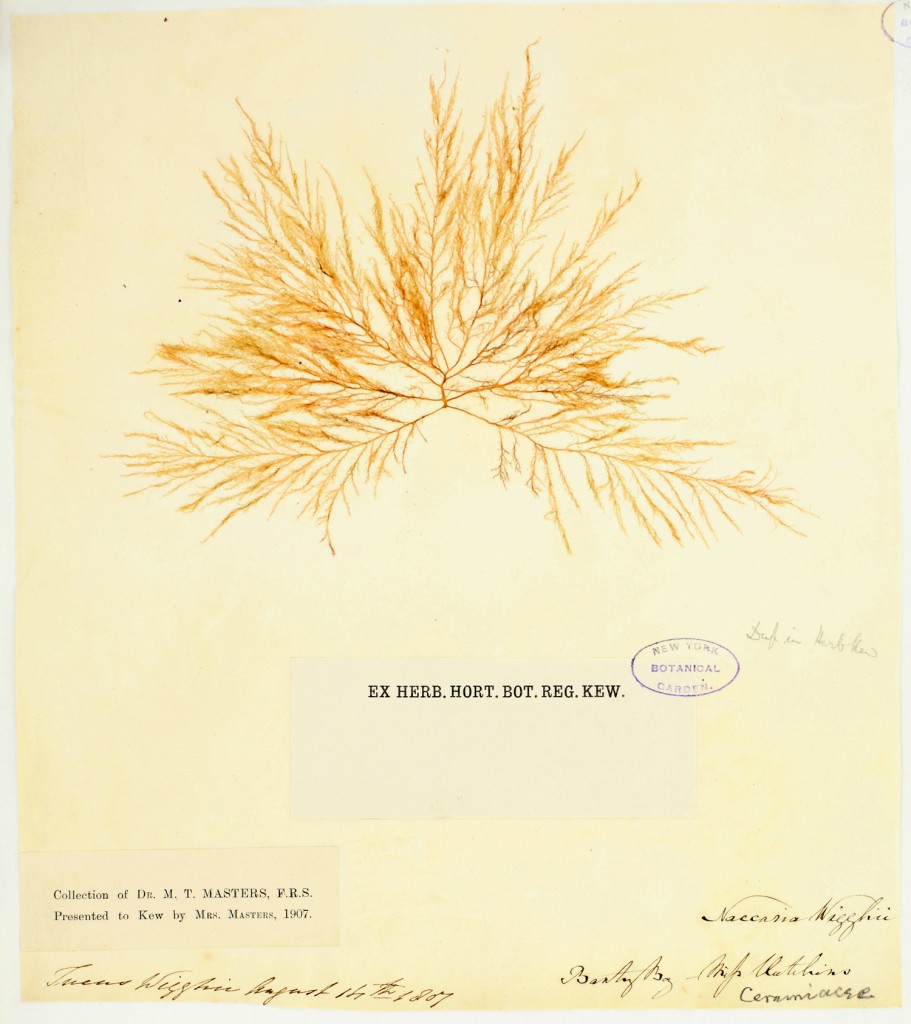

I recently happened across the oldest specimen that I have ever seen in the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. It was collected in August 1807 in Bantry Bay, Ireland, by a woman named “Miss Hutchins.” While digitizing lichen, bryophyte, and algal specimens over the last two years, I have become familiar with Miss Hutchins’ name. Her specimens appear to be some of the oldest in these collections, all dating from the very early 1800s. I finally decided to investigate: who was this Miss Hutchins?

As it turns out, her name was Ellen Hutchins. Born in 1785, she was Ireland’s first female botanist. Hutchins was introduced to botany after a period of illness by her physician, Dr. Whitley Stokes, who was also a botanist. He encouraged Hutchins to pursue the science as a way to improve her health. At the time, it was believed that the natural sciences were good for one’s health, because they provided outdoor exercise in addition to indoor activity. Dr. Stokes allowed Miss Hutchins to use his books and introduced her to other botanists.

When she returned to her home in Bantry Bay, Miss Hutchins continued to delve deeply into botany. She focused on cryptogams—plants that do not produce seeds, such as lichens, mosses, and algae. By 1806, she was sending specimens to botanist James Townsend Mackay. Mackay sent many of these along to botanist Dawson Turner, who was struck by the specimens and decided to correspond with Hutchins himself. Soon, Hutchins was discovering new species and rare plants, and many preeminent botanists took notice of her aptitude and tireless energy for collecting. She and Turner became great friends through their correspondence over the years. Also a proficient artist, Hutchins provided botanical illustrations for Turner’s book Historia Fucorum.

Unfortunately, Hutchins had a difficult home life. Much of her time was spent caring for an elderly mother and a brother who was paralyzed. In 1813, her troubles increased when she was forced to move out of her Bantry Bay home by her eldest brother, who had taken possession of the house. In 1814 her mother died, and soon Hutchins moved to the home of another brother, back in Bantry Bay. By this time, however, she had fallen ill and was wasting away due to a mercury “treatment” for her liver. During this stressful period, Hutchins said that her correspondence with Turner was “the one source of happiness in her life.” She died in 1815, just before her 30th birthday.

Despite her death at such a young age, Hutchins managed to become quite accomplished in the field of Irish cryptogamic botany, collecting many rare specimens and discovering new species. Many of the botanists who had admired her work named new species after her. In naming Conferva hutchinisae for her, L. W. Dyllwin wrote in his publication British Confervae that he “know[s] few, if any botanists, whose zeal and success in the pursuit of natural history better deserve such a compliment.” Elsewhere in that publication, he credits her as the collector of many specimens, mentions her observations about the morphology and habits of certain species, and includes a number of her botanical illustrations.

Upon her death, Ellen Hutchins’ personal herbarium was given to her friend and colleague, Dawson Turner. Since then, her specimens have been passed along to herbaria all over the world, including, fortunately, the Steere Herbarium.

Sources:

Dillwyn, L.W. (1809). British Confervae; or colored figures and descriptions of the British plants referred by botanists to the genus Conferva. pp. 1-87, 1-6 (Index and Errata), Plates 69, 100-109, A-G (with text). London: W. Phillips.

How lovely to find this well researched and well written tribute to Ellen Hutchins. I am one of a small number of relatives of hers, descended from her youngest brother, Samuel, and a regular visitor to Ballylickey, Ardnagashel and the Bantry area of South West Cork, Ireland, where some of the family still live. I am working with the Bantry Historical Society on a celebration of Ellen’s life and work, in the bicentenary of her death, on 9th February 1815. The celebrations will take place in Ireland’s Heritage Week 22 to 30 August.

Her death was just before her 30th birthday (17th March). This is the only correction I have to the information in your article! And a comment, Ellen and her mother’s move to Bandon in 1813 was said by one of her nieces to be because they were both in need of better medical advice than could be given in Bantry.

I did not know that any of her watercolours or specimens had got as far as New York! In the family, we have just one watercolour of a seaweed, which right now is on my kitchen table in Surrey, England, surrounded by letters of hers and other papers that I am using in my research on Ellen.

Ellen’s Wikipedia page is very weak, and I am trying to improve it in time for tomorrow, 9th February, which is the actual 200th anniversary anniversary of her death. Would you be willing to have any of your text used for this purpose, either by putting it up yourself, or me doing so?