Open Sesame: An Intern Works to Reveal the Mystery behind a Common Food Plant

Posted in Interesting Plant Stories on April 10, 2015 by Genelle Diaz

Genelle Diaz-Silveira is a master’s student in biology at New York University who is completing her thesis at The New York Botanical Garden.

In a world saturated with technology, it’s hard to remember the importance of plants to our daily lives. We depend on them for oxygen, food, medicine, clean air, and aesthetic pleasures, yet we devote less mental energy to them than we do to our smartphones and social media accounts.

Luckily, scientists at The New York Botanical Garden do spend some time thinking about plants. By documenting how plants function, how they are related to one another, and what they require from their environment, we aim to learn more about how life evolved on Earth and how we can continue to sustain it.

As a student researcher at the Botanical Garden, I’m doing my part by constructing a phylogeny—an evolutionary family tree—of the plant family Pedaliaceae. Commonly known as the sesame family, Pedaliaceae is rich in species that are both economically and medicinally useful. Examples include Sesamum orientale, which is cultivated for sesame oil, and Harpagophytum procumbens, which is used to treat joint pain caused by arthritis.

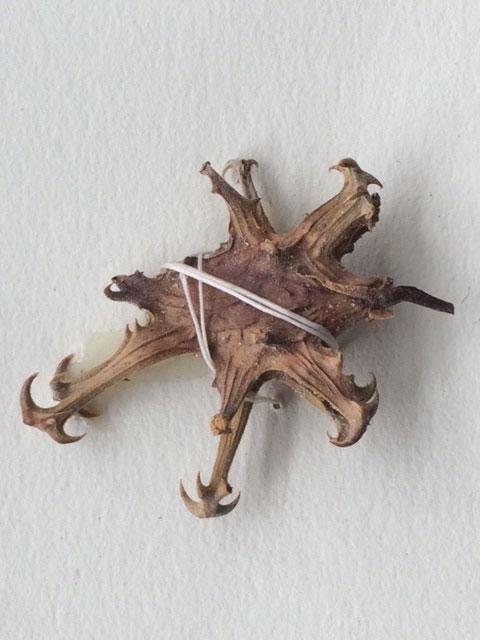

It’s the latter species—colloquially called “Devil’s Claw” due to its hooked fruit—that has inspired scientists here to resolve the muddied Pedaliaceae family tree. If we can paint a clear picture of how the family relates to its members as well as to those families closest to it, we may be able to forge a path to future drug discovery.

To elucidate the evolutionary history of Pedaliaceae, I’m primarily using molecular techniques. I’ve extracted DNA from multiple species—at least one representative of each genus—and begun to sequence different genes for each plant sample. The sequences will reveal genetic similarities and differences among my specimens. By analyzing the DNA data, I can come up with a good idea of how Pedaliaceae fits into the mosaic of plant life.

On its face, this may seem like a fairly straightforward endeavor. I obtain samples, extract DNA, sequence the DNA, and make a tree with the data. In actuality, the project has been full of mystery. That is to say, there are only a few contemporary scientists who have devoted time to Pedaliaceae, and herbarium specimens can be hard to come by in the US. These extra difficulties have made the journey extremely exciting.

Evolution can be messy; genetic distinctions among plant species are not always made clear by their physical characteristics. Unresolved families like Pedaliaceae often tentatively include orphan species that don’t clearly fit into one group or another. As this will be one of the first molecular studies of Pedaliaceae, I hope my results will provide enough evidence to definitively place those species. For the time being, I’m just happy to add to the naturalists’ tradition of cataloguing life.