Breakfast in a Blast: The Invention of Puffed Cereal at NYBG

Posted in Nuggets from the Archives on May 8, 2015 by Lisa Vargues

Lisa Vargues is a Curatorial Assistant at The New York Botanical Garden’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. Her work includes digitizing plant specimens, historical and new, from around the world for the C. V. Starr Virtual Herbarium.

In December 1901, Nathaniel Lord Britton, the New York Botanical Garden’s Director, reportedly (and understandably) appeared to be a little worried when a succession of blasts, sounding like gunshots, erupted from a third-floor lab in what is now the Library building. Thankfully, nothing was amiss. Botanist Alexander Pierce Anderson was immersed in a successful experiment that would not only prove a scientific theory but also transform breakfast for millions of people.

With suitable precautions, Anderson had used a hammer to crack open hermetically sealed and heated glass tubes, each containing corn starch, wheat flour, and, later, rice and other grains. All of the starch particles in the tubes had exploded, proving the theory, proposed by plant physiologist Dr. Heinrich Meyer, that a starch granule contains a miniscule amount of condensed water within its nucleus.

This water, “unable to escape during the heating period because of the pressure, had flashed into steam at the moment of the explosion and shattered the starch granule,” explained historian Harrison J. Thornton. Each rice grain, Anderson observed, had “expanded to eight or more times its original volume, while retaining its original form.” Other cereals reacted similarly. The cornstarch had expanded into a white porous mass. Realizing the commercial potential of his discovery, Anderson forged ahead to develop it into an enormously popular household staple: puffed cereal.

Anderson, born in Minnesota in 1862 to Swedish immigrants from Småland, had excelled in school, had worked from childhood into adulthood on his parents’ farm, and had taught in one-room schoolhouses. At age 27, he faced a series of life-changing hardships: over the course of just four months, both of his parents died, and a fire devastated the family farm.

His plans shifted. While earning B.S. and M.S. degrees in botany at the University of Minnesota and a Ph.D. at the University of Munich in Germany, he learned of the intriguing Meyer starch granule theory. Subsequent botanical work lead to a position as Curator of the Herbarium at Columbia University in New York City, with the opportunity to conduct research at the newly founded Botanical Garden.

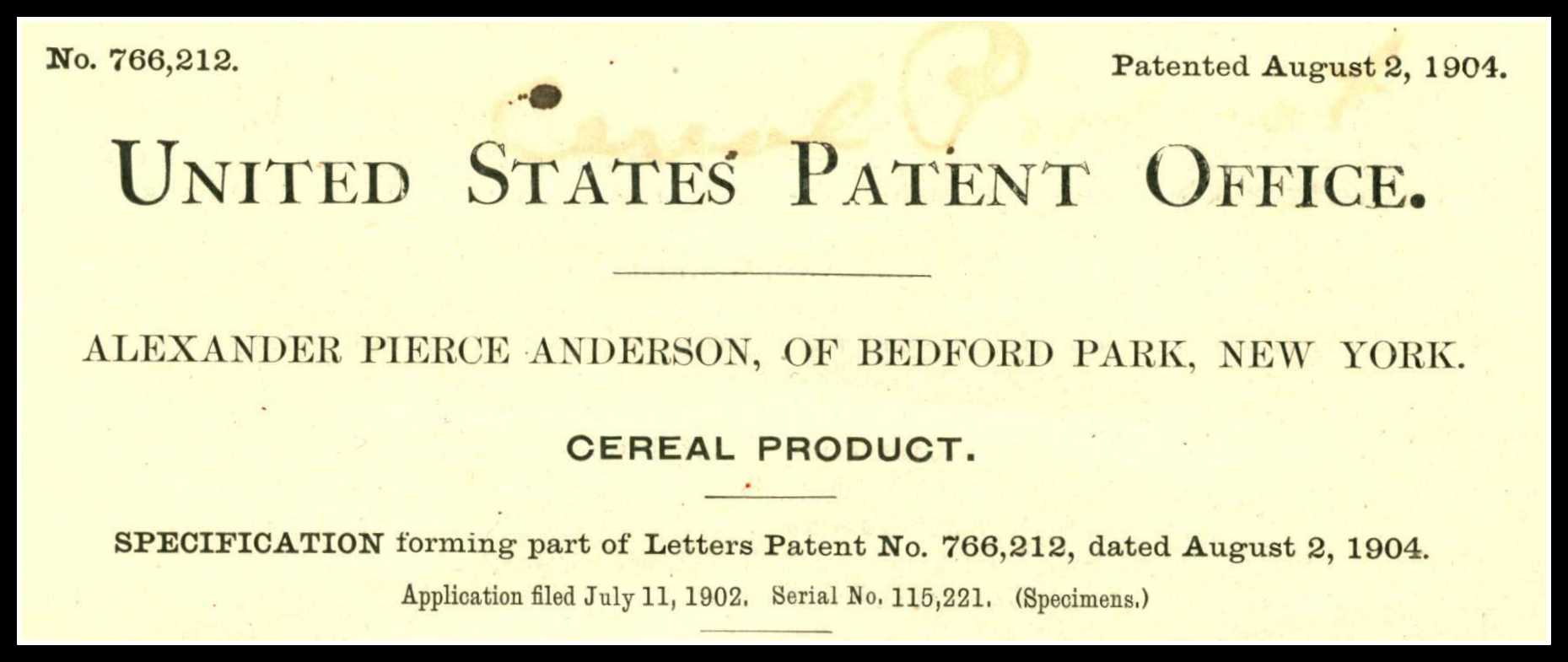

Anderson discovered that his puffing process was “applicable to nearly all starchy seeds and starchy substances, greatly increasing their nutritive availability” and emphasized that it is “entirely different from the ‘popping’ of corn or other grains.” In 1902, Anderson left Columbia and the Garden to focus on financing, patenting, and developing his process, leading to his longtime employment with the Quaker Oats Company.

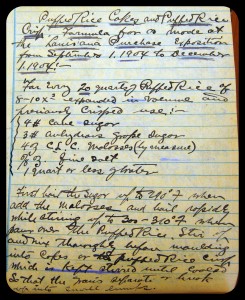

Prior to being marketed as a cereal, Anderson’s puffed rice was successfully promoted as a confection at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Cannon-like cylinders discharged downpours of puffed rice in a giant cage, wowing the crowds, who purchased packages of his novel treat. Eventually, Anderson’s puffed rice and wheat cereals were widely marketed by Quaker as “food shot from guns” and pitched in ads by major Hollywood stars such as Shirley Temple (who enjoyed puffed wheat with peaches), Bette Davis, and Bing Crosby. “Professor Anderson’s gift to food science” was one of many ad taglines launching him to fame.

Anderson’s prolific and wide-ranging research involved about 15,000 experiments within 35 years, including delving into aerodynamics and adhesives. During Anderson’s farming days, his father’s encouraging words, such as “Plow well and deep, and we will have a good crop next year,” inspired hard work and preparation, which clearly served him well throughout his life.

References & recommended further reading:

- Anderson, Alexander P. (May 1902). A New Method of Treating Cereal Grains and Starchy Products. Journal of The New York Botanical Garden, Vol. 3 (No. 29), 87-89. http://mertzdigital.nybg.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p9016coll22/id/34/rec/9

- Hedin, Lydia E., et al. (1977). Alexander P. Anderson, 1862-1943: A Biography of His Life Which Was Devoted to the Study of the Natural World. http://www.andersoncenter.org/PDFs%20for%20site/AP%20Bio%20opt.pdf

Retrieved from: http://www.andersoncenter.org/history.html - Johnson, Frederick L. (Spring 2004). Professor Anderson’s “Food Shot From Guns.” Minnesota History Magazine, 4-16. http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/59/v59i01p004-016.pdf

Retrieved from: http://www.mnhs.org/collections/ - Woodward, Carol H.. (August 1943). Creator of Puffed Cereal –and Benefactor of Science: The Life Story of Alexander P. Anderson, Who Made His Famous Discovery at The New York Botanical Garden Journal of The New York Botanical Garden, Vol. 44 (No. 524), 173-180. http://mertzdigital.nybg.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p9016coll22/id/530/rec/3

This is a FABULOUS contribution to the Plant Talk Blog. Thank you so much!