WFO at NYBG: Scientists From Around the World Meet to Advance Work on a Comprehensive Online Plant Database

Posted in Interesting Plant Stories on May 6, 2016 by Stevenson Swanson

Stevenson Swanson is the Science Media Manager at The New York Botanical Garden.

As if assembling a comprehensive, scientifically verified database of more than 350,000 plant species were not a daunting task to begin with, try doing it in only four years. That’s the ambitious goal the scientists working on World Flora Online (WFO) are racing to meet.

As if assembling a comprehensive, scientifically verified database of more than 350,000 plant species were not a daunting task to begin with, try doing it in only four years. That’s the ambitious goal the scientists working on World Flora Online (WFO) are racing to meet.

When it’s up and running, WFO will provide scientists, conservationists, political leaders, and other policy-makers with information they need to protect one of Earth’s most important resources—its plants.

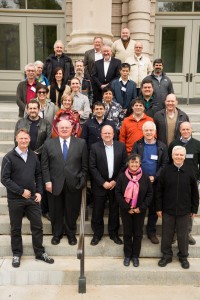

More than two dozen of the world’s leading plant scientists gathered at The New York Botanical Garden recently to review the progress that has been made on WFO and to plan the way forward so they can meet the goal of completing the database in 2020, which was established in the Convention on Biological Diversity, an international agreement.

As part of a week-long series of meetings at the Botanical Garden, several of the participants spoke about specific aspects of this monumental project during a symposium on Wednesday, April 27, in the Garden’s Ross Hall.

The presentations began with introductory remarks by Barbara M. Thiers, Ph.D., the Garden’s Vice President for Science Administration and the Patricia K. Holmgren Director of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. She noted that the Garden is one of four leading botanical institutions that are working together to coordinate the efforts of scientists and institutions around the world to create this first-of-its-kind online resource.

Among other things, the Garden is uploading to WFO scientific treatments of thousands of tropical plant species published by the NYBG Press in the Flora Neotropica series as well as digitizing and updating existing plant information from other sources. Garden scientists who are specialists in such important plant groups and families as mosses, palms, ferns, legumes, and many types of tropical trees and plants are involved in the work.

Peter Wyse Jackson, Ph.D., President of the Missouri Botanical Garden, which is also a principal partner in WFO, noted that 34 institutions have now signed on as members of the WFO consortium.

“That includes all of the key organizations in plant taxonomy and systematics worldwide,” he said.

Other speakers described the various approaches that are being pursued to bring together a huge amount of vetted data, which until now has been available only in bits and pieces at plant research collections or in individual publications. In some cases, the data has not been available at all.

That’s the case for the flora—the total plant life—of Nepal, a small Himalayan country with an incredibly diverse flora of some 7,000 plant species, according to Mark Watson, Ph.D., head of major floras at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, another of the four lead institutions on WFO.

“Nepal is a global biodiversity hotspot,” he told the symposium’s attendees. “There really was a knowledge gap. This spurred our interest in working with the Nepalese government to produce a flora.”

Unlike most other floras, however, which are published as books, this project is designed to be a “born digital” flora, which can be easily updated, will be available online, and will be exported to WFO.

In the case of Brazil—a large country with an almost overwhelming diversity of plant life—researchers there are working to increase ease of access to existing plant information by digitizing as many herbarium specimens of Brazilian plants as possible, including those at such important international collections as the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew (the fourth lead institution on WFO), the Natural History Museum in Paris, and the Garden’s Steere Herbarium.

This collaborative project, called Reflora, has so far made 1.4 million specimens available online, said Eduardo Dalcin, Ph.D., of the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden. The goal is to complete an online virtual herbarium and flora for all of Brazil’s plant species by 2020, so they can feed into WFO.

Similarly, researchers in South Africa—whose 21,000 plant species give it one of the most diverse floras in the world—are compiling an electronic flora from existing, mainly printed sources, said Marianne Le Roux, Ph.D., of the South African National Biodiversity Institute. That e-flora will also become a major contribution to WFO.

All of these projects look at the total plant life within one country. Another approach is to study one family of plants wherever they occur. That is the goal of a project to produce a worldwide study of the Solanaceae, or nightshade, family, which includes such important or familiar plants as potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants, and petunias.

It’s a huge, complicated family, with as many as 3,000 species. Sorting out the species and producing new scientific descriptions of each has already taken a decade, according to Sandra Knapp of the British Museum of Natural History. It too will feed into WFO.

“Why are we bothering to do all of this?” she said, looking out at the assembled scientists and other members of the audience in Ross Hall. “It’s to stop the loss of biodiversity. The thing [about WFO] that is going to last the longest is the integration from the global to the local and from the local to the global. The nexus is knowing what plants there are. WFO will make a huge difference to a lot of different people.”