Once Frozen in Ice, Now Frozen in Time: Artifacts of an Arctic Voyage

Posted in Nuggets from the Archives on September 23, 2016 by Lansing Moore

Sarah Dutton is a project coordinator in the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium, where she is working on a project to digitize the Steere Herbarium’s collection of algae.

It is 1879, and for months you have been living aboard a creaking wooden steamship trapped in miles of shifting Arctic sea ice. When you venture above deck, the air is icy as you gaze across the polar landscape. Among your companions are several officers, 21 crewmen, six other European scientists of various disciplines, and a few hundred indigenous Chukchi people who live nearby.

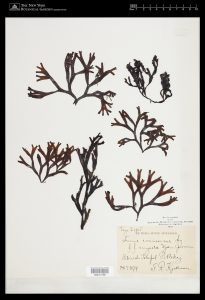

Such was the experience of Dr. Frans Reinhold Kjellman, a botanist aboard the SS Vega during the Swedish Vega Expedition. The New York Botanical Garden’s project to digitize the algae collection in the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium has uncovered two algal specimens that Dr. Kjellman collected during this expedition, providing glimpses into a little-known but fascinating story of 19th century science and exploration.

The tale begins with Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld, a Finnish-Swedish scientist and explorer, who had led many successful Arctic expeditions by the time he proposed the Vega Expedition. This time, he planned to circumnavigate the Eurasian continent via the Arctic Ocean and the Bering Strait, or “North East Passage,” to prove that this was a viable route between Europe and the Pacific. The scientists on board the Vega were prepared to gather data about the geography, hydrography, meteorology, and natural history of the Arctic, much of which was still unexplored by Europeans at the time. Kjellman, who had accompanied Nordenskiöld on three previous voyages, was an authority on Arctic algae.

The SS Vega departed Sweden on June 22, 1878. On September 3, the ship began to encounter sea ice. The explorers continued, hugging the coast and searching for a clear way through the increasing ice. However, by the end of September, the ice thickening in front them could no longer be broken by the ship’s hull. They had reached Kolyutschin Bay, the last bay before the Bering Strait, but a belt of ice less than 7 miles wide barred their passage. In his book, The Voyage of the Vega round Asia and Europe, Nordenskiöld expresses regret over time that could have been saved along the journey. He believed that had the ship arrived at Kolyutschin Bay just a few hours earlier, they would have been able to continue. To rub salt in the wound, Nordenskiöld later learned that an American whaler had been anchored only a couple of miles away in open water on the same day the Vega was frozen in.

The Vega’s crew and passengers prepared to keep the ship safe through the long winter. They allowed snow to accumulate on deck and swept snowdrifts up the ship’s sides to protect it from the cold. Thanks to the experienced Artic explorers on board and careful planning, the Vega was stocked with plenty of food and warm clothing, and extra food was kept on shore in case ice pierced the ship.

To judge from Kjellman’s account, the dreary days passed slowly:

The eye rests on the desolate…landscape, which is exactly the same as it was yesterday; a white plain in all directions, across which a low, likewise white, chain of hillocks… raises itself, and over which some ravens, with feeble wing-strokes, fly forward, searching for something to support life with.

Still, the scientists aboard the Vega used this time to collect many types of data. They kept a hole in the ice for tidal readings, took temperature readings several times every day, and built an observatory made of ice blocks on shore for magnetic observations. They made detailed notes about the customs of the native Chukchi people and acquired artifacts—sometimes by trade, sometimes by less scrupulous methods. Dr. Kjellman led the charge with botany, collecting both algae and land plants. One of his algae specimens that was found this year in the Steere Herbarium was collected in July 1879, less than 11 days before the Vega was free of the ice.

On July 18, 1879, the Vega finally broke free, and it passed through the Bering Strait shortly thereafter. Another of Kjellman’s algae specimens was collected in St. Lawrence Bay, just past the Bering Strait, two days after they had set sail again. This shows just how close the Vega had come to the key turning point in the voyage before it was trapped.

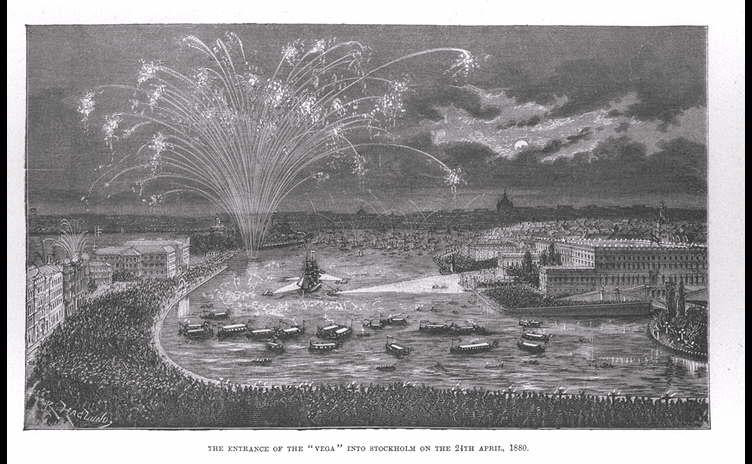

Yet Nordenskiöld accomplished his goals. The Vega was the first ship to pass through the North-East Passage and first to circumnavigate Asia. After many festive receptions throughout Europe, it reached Stockholm in April 1880.

The North East Passage did not turn out to be a very reliable shipping route between Europe and Asia until the advent of icebreaking ships in the 20th century. However, the legacy of the Vega expedition lives on in the historical and scientific data that was gathered, including physical collections like those now preserved in the Steere Herbarium.