At a Crossroads: Plants and the Endangered Species Act

Posted in Environment on August 16, 2019 by Brian Boom

Brian M. Boom, Ph.D., is Vice President for Conservation Strategy at The New York Botanical Garden.

The federal government recently announced plans to significantly weaken the Endangered Species Act (ESA), the most important legislation ever enacted to protect threatened plants and animals in the United States. There are currently 947 plant species and 1,471 animal species listed through the ESA. The new rules, which will take effect next month, will curtail future listings and potentially reverse a half-century of salvation in the wild. An article in The New York Times outlines the plans; most of the response and commentary has focused on animals—for instance, Carl Safina’s compelling opinion piece with statistics about triumphant saves of condors, alligators, grey wolves, and pelicans since the act became law in 1973.

However, the new rules also have grave implications for plants.

At risk due to degradation of land, pollution, soil erosion, and invasive species, threatened and endangered plants will be even more impacted by a weakened ESA than will be animals. The relatively greater risk to plants is due to a phenomenon called plant blindness—modern society’s inability to fully comprehend and appreciate the vital roles of plants in human and ecosystem well-being.

The ESA has been successful in saving many species, and not only animals. For plants, which were first listed in 1977, eight species to date have been “delisted,” officially removed from those listed under the Act because their populations are in strong recovery mode. These species are Robbins’ cinquefoil (Potentilla robbinsiana), Eggert’s sunflower (Helianthus eggertii), Maguire daisy (Erigeron maguirei), Tennessee purple coneflower (Echinacea tennesseensis), white-haired goldenrod (Solidago albopilosa), Eureka Valley evening-primrose (Oenothera avita ssp. eurekensis), Hidden Lake bluecurls (Trichostema austromontanum ssp. compactum), and Deseret milkvetch (Astragalus desereticus).

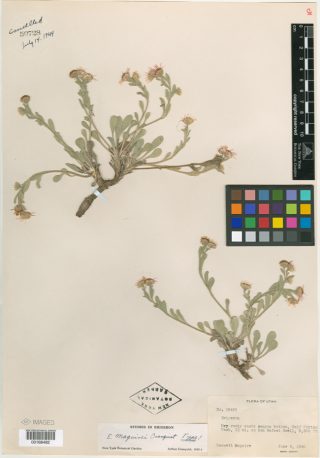

The story of the Maguire daisy, named in honor of the late legendary NYBG botanist Dr. Bassett Maguire, is emblematic of these success stories. When it was listed in 1985, the Maguire daisy was known from only one location in Utah with a population of seven individuals. This species had been listed because of cattle grazing, mining, and recreation pressures in the area. Ten years after listing, there were 32 populations with a total of some 5,000 individual plants. By 2011, the year it was delisted, the Maguire daisy was known from 118 sites with a total of over 164,000 individuals. This and the other seven delisted species probably owe their survival to the ESA.

The success of the ESA can be measured not only by the numbers of species that have been delisted, but also by the species’ rates of recovery. For example, mountain golden heather (Hudsonia montana), found only in North Carolina, is still listed as threatened because the goals of its recovery plan have not yet been fulfilled, but nonetheless this species increased from 2,883 plant clumps in 1982 to 10,301 in 2009, which is progress and a success thanks to the ESA. About 90 percent of plant and animal species still on the list are recovering at the rate specified by their individual federal recovery plans.

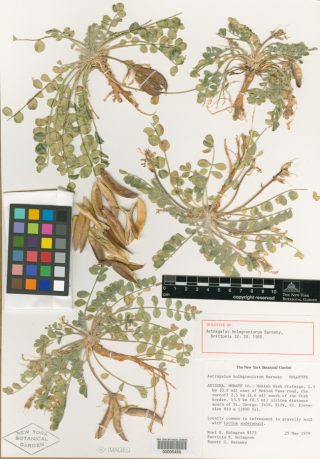

NYBG is well-positioned to lead in helping to safeguard the remaining ESA listed plant species. Since its founding in 1891, NYBG scientists and horticulturists have been tireless in their stewardship responsibilities. We have actively collected and documented the plants of our country, as evidenced by the more than two million preserved plant specimens from the United States in our William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. Many of the plant species listed through the ESA have specimens in the Steere Herbarium that authenticate their distribution and help make the case for their survival. Consider the Holmgren milk-vetch (Astragalus holmgreniorum), named in honor of Curators Emeriti Drs. Noel and Patricia Holmgren. It continues in existence because of our research, supported by the power of the ESA, under which this species was listed as endangered in 2001. Three small populations exist in Washington County, Utah and adjacent Mohave County, Arizona.

Herbarium specimens have many other scientific applications. They have been used to monitor carbon dioxide concentrations in the air and the level of air and soil pollutants. They allow study of changes in the timing of plants’ leafing, flowering, and fruiting times. They permit us to track and monitor the expansion of invasive species. They are a source of DNA, which helps us understand the genetic basis of key traits that help plants adapt to particular habitats, perhaps leading to breeding programs to make our key food sources more resilient. They enable us to model future species’ distributions in light of projected environmental changes, including biodiversity loss and global warming.

They are also one of the key research resources for our scientists, allowing them to publish authoritative accounts of the plants of much of the country, such as Intermountain Flora, covering the region between the Rocky and Sierra Nevada Mountains, and the Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada. Current research, such as Dr. James Lendemer’s project on lichen diversity in the Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain and Dr. Robert Naczi’s project to completely revise the Manual of Vascular Plants, are examples of NYBG’s ongoing active engagement with the flora of the United States.