The last decade has given rise to many conversations about African American contributions to the national cuisine, so the opening of African American Garden: Remembrance & Resilience is timely; especially as we embed Juneteenth as a holiday for the entire country to celebrate.

When I was asked to curate the Poetry Walk, I immediately thought of my UpSouth grandmother, Willie Mae, and the garden of collard greens, tomatoes (and possibly even corn!) that she cultivated behind a typical row house, in the predominately-Black city in which I grew up. Then the images, from the family albums, of my great grandparents—all of whom were sharecroppers—came to mind. And beyond them, the generations of my enslaved ancestors whose toil seeded the great wealth from which we benefit today. That complicated history has long produced associations between African Americans and the fieldscapes, and kitchen scenes of our art, so this garden is well-placed in the larger exhibition, Around the Table: Stories of the Foods We Love.

What, however, does our poetry say about the Black presence in America’s gardens and, more widely, a post-Emancipation relationship to land beyond ownership? Anne Spencer (1882–1975), poet and doyenne of the Harlem Renaissance, was a meticulous gardener, and her poems often reflect having been composed within sight or among the flowers and herbs she grew. The excerpt from my own poem, “Pelham” braids a biography of my maternal great-grandmother and her foraging skills, with historical narratives of the enslaved; Lucille Clifton’s “cutting greens” is a philosophical spatial-warp from the microcosm of her kitchen to the macrocosm of the universe; while Thylias Moss’ “Sweet Enough Ocean, Cotton”, offers a deep meditation on a small field; LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs, throws open the doors of the wide celebration that is the African diaspora, and Ross Gay allows a glimpse of the symbiosis that exists between a human and a tree; until Camonghne Felix returns us to the grandmother—and the perennial gift of her wisdom.

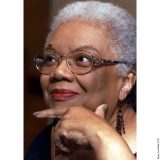

Perhaps, with her groundbreaking anthology Black Nature (a temporal sweep of Black poets examining individual environments and questioning shared geographies), Camille T. Dungy extends the perfect invitation: