The Seeds of Our Future

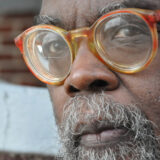

An introduction by Dante Micheaux, Director of Programs for Cave Canem Foundation

In her sweeping epyllion, “Amistad,” the poet and scholar Elizabeth Alexander writes: “After the roiling of the Atlantic, the black Atlantic, black and mucilaginous.” After? What an appropriate question with which to enter Diaspora: Same Boat Different Stops. Though Alexander’s poem tells the story of a famed mutiny, immortalized in film by the heroic Djimon Hounsou’s Cinque, the Black presence in the American hemisphere is perpetuated by the evidence of our ancestors. The African American Garden is a bounty of evidence—a biological and temporal map of how they cultivated and nourished several generations, who remember a grandfather’s secret blend of house pepper or an aunt’s hands stained blue from a green bush. There is, too, the dauntless telling of our foremothers braiding grains of rice and seeds into their hair, before the boat—carrying our futures, through trauma, on their heads.

When one imagines the landings of those futures, in Salvador da Bahia, Yurumein, the southern United States and elsewhere, a taste of frango com quiabo, darasa or sweet potato pie is not far behind. The poems along this garden’s poetry walk take the fruits of the earth and weave them into our songs and myths, into the account of ourselves and add to the evidence of our existence.

Kalamu ya Salaam sings of what fuels us in “The Spice of Life” from his suite of New Orleans Haiku; there is a vigilant mother in Stephanie Pruitt-Gaines’s “Mississippi Gardens,” who looks open-eyed at the callousness of enslavement; Agnes Maxwell-Hall paints the colors of a food hawker’s pitch in “Jamaica Market”; Cyrus Cassells’s sublime “Wild Indigo, Because” sees a people bodytired by agricultural labor still able to find astonishment in the wealth of a plant; the vegetation avenges the victims of colonialization in Anacaona Rocio Milagro’s “Morir Para Vivir Mi Palomita Blanca”; Wingston González filters a meditation on our evolution through the prism of the natural world in “The Path and the Sowing”; and Ricardo Aleixo returns the god of thunder to us from our ancient religion, cooking yams, in his poem “Xangô.”

Feast on the evocation of foods, hues and histories of the African diaspora…and be grateful!