100 Years of Daffodil Hill: The Women Who Kept it Going

It’s one of our favorite seasons at NYBG. Soon, the lawn on Daffodil Hill will give way to a sea of pale yellow as thousands of cream-colored bonnets blanket the grass. Their beauty and hypnotic fragrance are tell-tale signs that warmer weather is near.

Though Daffodil Hill is well-known and well-loved, its history is less familiar to garden-goers. This year marks a century after its creation, and with March being Women’s History Month and the official start to spring, we’re honoring the women who made our beloved Daffodil Hill possible.

In 1898, seven years after NYBG was founded, our collection began with a gift from Peter Barr, a British horticulturist credited with helping popularize these sunny flowers. Though Barr’s contribution kicked things off, it was Ethel Anson Peckham (1879–1965) whose work led to the rapid expansion of our collection and the establishment of Daffodil Hill.

Ethel Anson Peckham with guests on Daffodil Hill, 1924

Hailing from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and later living in New Rochelle, New York, Peckham was no stranger to the east coast climate and enthusiasm for horticulture. An avid gardener whose life was defined by a passion for irises and daffodils—two iconic spring flowers in American gardens—her botanical history was tied to NYBG long before the first whisperings of Daffodil Hill.

In 1920, she helped establish the American Iris Society (AIS) and its first trial and demonstration garden of iris, for which NYBG offered its facilities. For a decade starting in 1925, Peckham served as director of AIS. One of her long-lasting impacts on the AIS is as editor and compiler of the 1929 and 1939 Alphabetical Iris Check Lists, which listed tens of thousands of iris names, horticultural varieties, and other species-specific information. It was a massive and important undertaking, and Peckham’s meticulous work set a precedent for lists and catalogs that followed. H.H. Everett, Director of AIS in the late 1930s, introduced these with a note,

To those of you who feel this ‘Check List’ is purely factual, let me assure you that it is far more than that. It is a book of high adventure in the field of beauty, a record of hopes achieved, and a guide to Rainbow’s end. A book for study on cold winter evenings when you can plan new beauty for our gardens.

I hope you will join with me in full appreciation of the unselfish hours of toil spent by its compiler through these many years.

Through all of her tireless work, Peckham’s attention remained on NYBG. In 1924, she purchased 10,000 bulbs using a fund she created. She supervised their planting, along with 37,000 more that were gifted from the Dutch Bulb Exporters Association that same year. Peckham was named NYBG’s Honorary Curator of Iris and Narcissus Collections in 1927. She continued to raise a significant amount of money to maintain the daffodil collection, and regularly contributed to The Journal of The New York Botanical Garden and the Garden’s Addisonia: Colored Illustrations and Popular Descriptions of Plants. Her musings on daffodils and irises are available to view through our archives at the Mertz Library.

The stewards of Daffodil Hill form a long thread of women—and Claire Lyman, previously NYBG’s Associate Curator of Living Collections, and now Administrative Manager for the Science Division, is carrying the baton in a very similar fashion to Peckham.

In 2019, Lyman took on a project to document the various daffodil varieties on Daffodil Hill. Though we know these flowers typically as “daffodils,” this is the common name for members in the genus Narcissus. Many of those we see at NYBG and in most gardens today are hybrids, or cultivars—varieties that are selectively bred from wild and native species to create more favorable characteristics.

Daffodil Hill blooming in 1933

For Lyman, documentation seemed at first to be an easy task, intended for a simple brochure on the daffodil varieties. It was originally thought that there would be 20 to 40 different daffodils, with most being modern cultivars. She went out to photograph the familiar, known plantings, and work backwards to identify them. But when she got there, she was overwhelmed with the magnitude of unrecognizable flower faces.

Lyman came back with photographs of 130 unique and unfamiliar daffodils.

The first planting on Daffodil Hill was “naturalized”—meaning many different varieties were incorporated in many different areas, hence a “natural” or “wild” look. And to make it even harder, this collection was not documented—so no singular record existed to identify all the historic varieties on Daffodil Hill.

Many of the unfamiliar daffodils Lyman found were heirlooms, or historically cultivated varieties. A number of these are no longer in commerce, having been superseded by newer and more exciting hybrids, and therefore are difficult to identify. Heirlooms can be hard to distinguish from one another. They are similar in appearance, and more closely carry on characteristics of the original Narcissus species from which they were bred—willowy, with thinner petals and stems that dance in the wind.

More modern hybrids have thick and strong stems that don’t bend when they’re wet, and “good substance” petals that are sturdier and won’t lose their luster if wind rushes through. Lyman compared them to lollipops.

With the newfound knowledge that many of the varieties on Daffodil Hill are heirlooms that have been blooming since the first planting, Lyman knew she would have to dive into the past. She set to work on a cataloging project that echoed Peckham’s work almost a hundred years before—one that was both ardent and arduous, painstaking and passionate. She continuously returned to Peckham’s writing and records to look for information.

“I went through all of the journals, the bulletins, even articles and external articles that were written about this collection,” said Lyman. “Every time they mentioned a cultivar, I wrote that down and created a reference to where it was pulled from.”

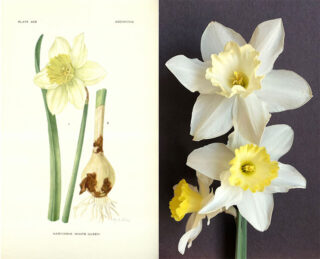

A botanical illustration of Narcissus ‘White Queen’ by Ethel Anson Peckham, Courtesy of DaffLibrary, and an image of Narcissus ‘White Queen’ by Claire Lyman.

After determining every variety that had been specific to the naturalized planting, Lyman whittled her identification down to 28 heirloom cultivars, with several more tentatively identified. You can read more about the project here, view the cultivars she documented here, and read how to identify daffodils here.

Why is this work important? Why did Peckham and Lyman, a century apart, put in so much effort to understand the story behind a flower?

“Being a well-known historic institution, records are the bread and butter of what we are,” said Lyman. “Collections are only as good as the records…we need to talk about these collections to our visitors and educate them on our collections.”

As the stewardship of Daffodil Hill passed from hand to hand, documentation became blurry, but motive never strayed.

“In the Garden’s initial stages, some of the most important people that really left a significant footprint on certain collections were not paid,” said Lyman. “These experts came in…out of the good of their own heart.”

NYBG’s daffodil collection only continues to grow. To celebrate the 125th Anniversary of NYBG, The Million Daffodil initiative was launched in the fall of 2015 in order to expand our daffodil collection for generations to come. Work continues to be done on our historic collection, especially to understand how heirloom daffodils have thrived over the past century. Studying the past is not only important to inform the future, but also to gain appreciation for what once was. To Lyman, it’s especially important to recognize the beauty of heirloom varieties before their flashier descendants became popular.

“We did a lot of work in the last two years in lifting, dividing, and replanting some of these historic varieties that have persisted for a very long time in efforts to sort of make this collection more sustainable,” said Lyman. “Understanding the collection better helps us preserve it better, to flourish in the future.”

Over the years, many women enabled the continued care and expansion of Daffodil Hill through their generous support. Foremost among these philanthropists were Kit Pannill, a prominent plantswoman whose husband, Bill, was a daffodil breeder who hybridized many popular modern cultivars; Anna Glen Butler Vietor and her family; and two NYBG Trustees, Marjorie G. Rosen and Mrs. Harry Burn III.

Because daffodils flower annually, they bring beauty to the Garden each spring—and this season’s is no exception! Not only that, but our daffodils also continue to surface as a reminder of how a love for flowers and dedication to botany can give way to the growth of a garden, and to spring splendor for years to come. Become part of Daffodil Hill’s next hundred years by dedicating a new daffodil planting in honor or memory of a loved one.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.