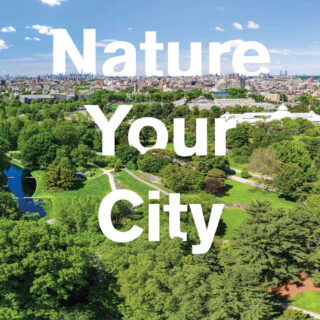

A No-Brainer for Climate Action: Nature Your City

Eric W. Sanderson, Ph.D., is Vice President for Urban Conservation Strategy, and Lucinda Royte is the Urban Conservation Research Assistant at The New York Botanical Garden.

Is there any lever more powerful than cities to effect climate action?

Why cities? First, because that’s where most people live. And people are the primary driver of climate change [1]. The United Nations estimates more than 55 percent of the world’s population [2] is already urbanized (up from 10 percent a century ago) and most estimates suggest that by 2100 more than 70-80 percent of the world’s population will be living in towns and cities [3].

Second, cities, especially cities NOT built around the automobile, are much more carbon efficient on a per person basis [4]. Compact towns and cities use less fossil fuel per person on average because commuting distances are shorter, availability and use of public transportation more likely, and living spaces smaller with greater proportion of shared walls and therefore shared heating and cooling costs. Electrification of public transportation, heating, and cooling systems, which is already readily achievable, paves the way for a transition to renewable energy.

Third, cities by definition concentrate people, which mean they concentrate human ingenuity, wealth, volubility, and, in the best of circumstances, cooperation. As the C40 Cities initiative has taken pains to point out and facilitate, cities are also a level of government where experimentation can happen, less burdened by regional- and national-level political exigencies.

Less happily, cities are also where people are most likely to feel the impacts of climate change [5]. Many of the cities of the world are coastal, so sea level rise is an important and pressing issue [6]. Even in non-coastal cities, many urbs have grown up beside large rivers or in floodplains [7], where flooding has and will continue to be exacerbated by climate change. Cities are also hot, a result of the intensity of infrastructure; all those hot streets and walls re-radiate heat, especially in summer.

How do we make cities livable, more resilient, and cooler? Nature, friends, nature. Nature is our ally and our co-conspirator for a better world. Nature comes in many forms in the urban environment: green roofs, street trees, bioswales, riparian corridors, parks, forests, wetlands, grasslands, beaches, and dunes. Anywhere a plant can grow, a plant should grow, making for a better city. It may seem ironic but the best way to make bigger, more efficient, more livable cities is to restore some of the nature that predates the metropolis.

At The New York Botanical Garden (NYBG), where plants are our gig, our approach to urban conservation has four elements: (1) historical ecology, (2) ecological democracy, (3) active restoration, and (4) environmental governance. New York’s green past, explorable on welikia.org, helps us understand the lessons nature has to tell about climate adaptation and multi-dimensional solutions [8]. Ecological democracy using tools like our visionmaker.nyc platform enables everyone to see the city as an environmental good and contribute their ideas for making those goods better and more valuable. Active restoration builds on NYBG’s long-honed horticultural and ecological expertise to restore native ecosystems, appropriate to the landscape and climate, in cities. Environmental governance is about building the policies and procedures that enable cooperation and joint action toward a more climate resilient city. Bureaucracy in the service of nature!

Imagine a world where everyone who lived in cities knew local nature from daily, personal experience. Their houses and businesses weren’t flooded because we gave the water some place to go, streams and ponds flowing through neighborhoods. Imagine our neighborhoods were cooler because of the shading and evaporative cooling that plants and open waters provide. Cities that work with nature instead of against it would good places to live, for residents enjoying green, ecologically democratized, and beautiful precincts where they avail themselves of good jobs, good friends, and the opportunity to live their best lives on their own terms, which, not incidentally, also help to mitigate climate change. The great thing about cities is they incentivize choices that are both human-centric and climate friendly, because doing what the climate needs is the best, most convenient, most remunerative, and enjoyable way for people to live, when you live in town.

Cities are the most powerful lever we have to pull to address climate change.

Want to learn more? Come join us at NYBG for a walk in the cool, life-filled woods in the heart of the green Bronx.

This post is part of NYBG’s coverage of COP28 and the multilevel action, urbanization and built environment day. Learn more at COP28.com

[1] https://www.ipcc.ch/2021/08/09/ar6-wg1-20210809-pr/

[2] Urban Development. (2023). [Text/HTML]. World Bank. Retrieved December 1, 2023, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview

https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/news/world-urbanization-prospects-2018

[3] Sanderson, E.W. Watson, J., & Robinson, J. G. (2018). From Bottleneck to Breakthrough: Urbanization and the Future of Biodiversity Conservation. BioScience, 68(6), 412–426. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biy039

[4] Brown, M. A., Southworth, F., & Sarzynski, A. (2008). Shrinking the Carbon Footprint of Metropolitan America.

Newman, P., & Kenworthy, J. (1999). Sustainability and Cities: Overcoming Automobile Dependence (1st ed.). Island Press.

Glaeser, E. L., & Kahn, M. E. (2010). The greenness of cities: Carbon dioxide emissions and urban development. Journal of Urban Economics, 67(3), 404–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2009.11.006

[5] Gu, D., & Division, U. N. P. (2019). Exposure and vulnerability to natural disasters for world’s cities. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

[6] Extreme Weather Response Task Force. (2021). The New Normal: Combating Storm-related Extreme Weather in New York City. Department of Environmental Protection.

MacManus, K., Balk, D., Engin, H., McGranahan, G., & Inman, R. (2021). Estimating population and urban areas at risk of coastal hazards, 1990–2015: How data choices matter. Earth System Science Data, 13(12), 5747–5801. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-5747-2021

Neumann, B., Vafeidis, A. T., Zimmermann, J., & Nicholls, R. J. (2015). Future Coastal Population Growth and Exposure to Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Flooding—A Global Assessment. PLOS ONE, 10(3), e0118571. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118571

[7] Goldbaum, C., ur-Rehman, Z., & Hayeri, K. (2022, September 14). In Pakistan’s Record Floods, Villages Are Now Desperate Islands. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/14/world/asia/pakistan-floods.html

Moses, C. (2023, August 8). Torrent of Water From Alaska Glacier Floods Juneau. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/08/us/alaska-juneau-flooding.html

Devitt, L., Neal, J., Coxon, G., Savage, J., & Wagener, T. (2023). Flood hazard potential reveals global floodplain settlement patterns. Nature Communications, 14(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38297-9

[8] Sanderson, E. W. (2013). Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City (Illustrated edition). ABRAMS Books.

San Francisco Estuary Institute (2019). Urban Ecological Planning Guide. Retrieved October 20, 2020, from https://www.sfei.org/sites/default/files/biblio_files/UrbanEcologicalPlanningGuide_Final_062119.pdf

Whipple, A., Grossinger, R., Rankin, D., Stanford, B., & Askevold, R. (2012). Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Historical Ecology Investigation: Exploring Pattern and Process. SFEI.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.