Backstory, Front-story, Overstory, Understory

Timothy Dalton is an NYBG-CUNY Graduate Fellow at The New York Botanical Garden.

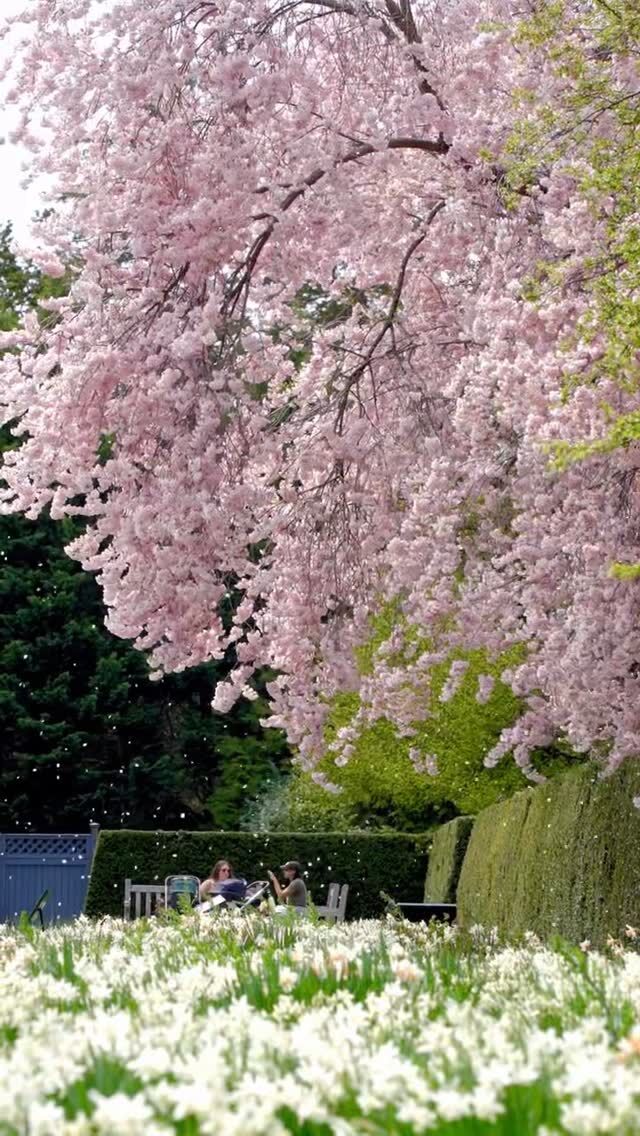

This spring, the built world shut down just as the natural one opened up. As emergency and crisis faded into remote school and quarantine, the question of the relationship of New Yorkers to their green spaces took on an urgency and depth I never expected when I proposed it in mid-February to the Humanities Institute at The New York Botanical Garden. The research questions I’d posed connecting “parks, plants, and people” in my late-winter application were originally couched in the past, specifically the period between 1854 and 1901. Yet, in March, and in April, the mortal persistence of those questions in our uncertain present made it nearly impossible to approach an answer. How did built green space imagine its users? “You get story after story of people who find these spaces life-saving,” the late community gardening advocate Edie Kean once said. This April, William Friedman, head of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, gave city parks essentially the same designation. Perhaps, then, that’s one answer: we imagine that plants can save us from ourselves.

We were—and still are—an anxious country seeing a generational health crisis basically mishandled at nearly every level. Yet, to Friedman, one early solution to the anxiety of April was “baked into every city in the country,” spaces like those designed by Frederick Law Olmsted. Olmsted, Friedman notes, was a former head of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, and “knew a thing or two about contagious diseases when he designed these great urban public spaces.” With all this in mind, I turned to the work of another writer and parks advocate with a record of public service in public health, John Mulally.

Best known as the founder of the Bronx Parks system, which includes The New York Botanical Garden, Mullaly was an immigrant from Belfast and a talented journalist. His anti-abolitionist, anti-draft writings as editor of the Metropolitan Record fueled the racist violence of New York’s Draft Riots of 1863. These writings have recently led local activists to argue, compellingly, that the city rename a park just north of Yankee Stadium. Two of these articles, “The Coming Draft” and “Five Hundred Thousand More Victims to Abolitionism,” led to an order for Mullaly’s arrest on charges of inciting violence. This writing unfortunately taints the rest of Mullaly’s work. The Milk Trade of New York and Vicinity (1853) and New Parks beyond the Harlem (1887) are united by their concern for the health of the people he viewed as belonging to working-class New York. In October 2020, I can’t read these works without seeing who Mullaly leaves out, whose health—indeed, to borrow Edie Kean’s phrase, whose life—he was not looking to save.

Curiously, the shadow of his work as a Copperhead hack does not pervade his writing on the undersea telegraph cable. That revolution in telecommunications relied heavily on mass harvesting of a single tropical tree with “invaluable properties,” the gutta-percha. Mullaly’s quick, seemingly awe-struck mention of gutta-percha led me to other primary and archival sources, to photographs and illustrations and descriptions of a host of species within the genus Palaquium. I arrived, finally, at an account of the devastating effects of gutta-percha harvesting in the Southeast Asian colonies of the British Empire written by John Tully, an Australian historian and novelist. My initial proposal centered 1854 for its seeding of the seductive, stereoscopic confluence of events that the Gilded Age seems to specialize in—think The Devil in the White City, think Ragtime. The same undeniably American and tragically enduring story that weaves technology, health, nature, and race converges in miniature in the figure of John Mullaly.

This biographical sketch may cast him as a cautionary emblem of the too-human capacity to look at the world and see some things backward, some clear as day, and some with a vision for which we have to fight with all we’ve got. But I’m grateful that he brought me, finally, to a plant that potentially offers scholars and students in a range of disciplines across a pandemic-dispersed university a global version of the same confluence. Not a moment too soon, it’s time to see what we can all learn from the gutta-percha. The lives we save may be our own.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.