Comprehensive Guide to Poisonous and Injurious Plants Published by NYBG and Springer

Michael J. Balick, Ph.D., is Vice President for Botanical Science and Director and Senior Philecology Curator of the Institute of Economic Botany at The New York Botanical Garden.

Lewis S. Nelson, M.D., is Professor and Chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine and Director of the Division of Medical Toxicology at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark, New Jersey.

Poison control centers in the United States recorded nearly 48,000 plant-related calls in 2016. While a small percentage of overall calls, it is a significant number, as many of these calls involved children under 5 years of age. Plants such as pokeweed (Phytolacca americana L.), poison ivy relatives (Toxicodendron species), chile peppers (Capsicum species) and Prunus species (including cherries and apricots, whose crushed pits can be dangerous to ingest) top the list. In the past few decades, the diversity of available cultivated plants—indoor and out—has increased dramatically. With the continued rise of gardening as a hobby, people introduce all sorts of novel species into their environments, and some of these contain toxic compounds or otherwise can cause harm.

Recently, The New York Botanical Garden and Springer published a new edition of our comprehensive reference book, Handbook of Poisonous and Injurious Plants. The earlier, second edition, published by NYBG and Springer in 2007, provided information about plants that might cause toxicity because of their chemical composition, such as species in the nightshade family (Solanaceae); injury to the mucosal tissue inside the mouth, such as species in the arum family (Araceae) that contain small, needle-like calcium oxalate crystals; contact dermatitis, such as the sumac family (Anacardiaceae); and many other harmful effects that plants can have on humans. This book helped advise health care workers, such as emergency physicians, about the identification of plants in cases of suspected poisonings, as well as gardeners, parents who wanted to take precautions as their children experimented with nature, and others who were curious about the plants in their environments.

Fruits in the genus Prunus, including apricots, cherries and plums all have kernels with seeds that contain amygdalin, a cyanogenic glycoside. The native black cherry, Prunus serotina, also contains this compound in its seeds. Despite this potential toxicity, a significant number of these cyanide-laced seeds must be eaten to cause severe toxicity.

By 2020, it was time for a new edition, as information provided in the book had changed. The most important paradigm shift is the way in which cases of suspected plant poisonings are treated by physicians and other health care providers. Previously, aggressive gastrointestinal decontamination was recommended, but this practice is now de-emphasized, with syrup of ipecac, a plant-derived product that has long been a staple in our medicine cabinets, nearly removed from standard treatment. One recommendation in this new edition is the use in some cases of orally administered activated charcoal, which absorbs chemical toxins. Interestingly, charcoal has a long history of traditional use in treating poisonings and wounds and purifying water, perhaps going back as far as ancient Egypt. Developed in the 1800s, activated charcoal—a special form of carbon with minute pores that increase absorbability—was used widely during the 19th century for the treatment of poisoning and is now thought to be less harmful than, and at least as equally effective as, previously used treatments.

Plants in the family Araceae, including Monstera deliciosa, contain calcium oxalate crystals which, if eaten, irritate and inflame the mucosal membranes of the mouth, and can result in pain and even difficulty breathing. Interestingly, the ripe fruits of Monstera deliciosa, as the name implies, are edible and delicious, and taste similar to pineapple. However, eating too much of this sweet pulp can cause a laxative effect.

From the botanical perspective, plant names have changed over the years, as have the plant families in which some species are placed. With recent progress in our understanding of plant evolution, botanists who study plant classification are able to assign species to families with greater precision. Correct species identification is critical to guiding management of the suspected poisoning, and misidentification must be avoided if at all possible.

Knowing the correct plant family is also important to providing informed treatment. Species in the family Solanaceae, such as Atropa belladonna and Datura species, contain toxic compounds such as atropine and scopolamine and share common effects to produce similar clinical syndromes. However, changes in plant names can pose a challenge to those who need information immediately to devise a therapeutic treatment. For example, the toxic species Duranta repens is now understood more correctly to be Duranta erecta. Yet much of the toxicological literature quickly accessible to a health care provider might still be under the first name and could be missed if only the second name is used in a literature search. To address this situation, the book provides both names for the same plant.

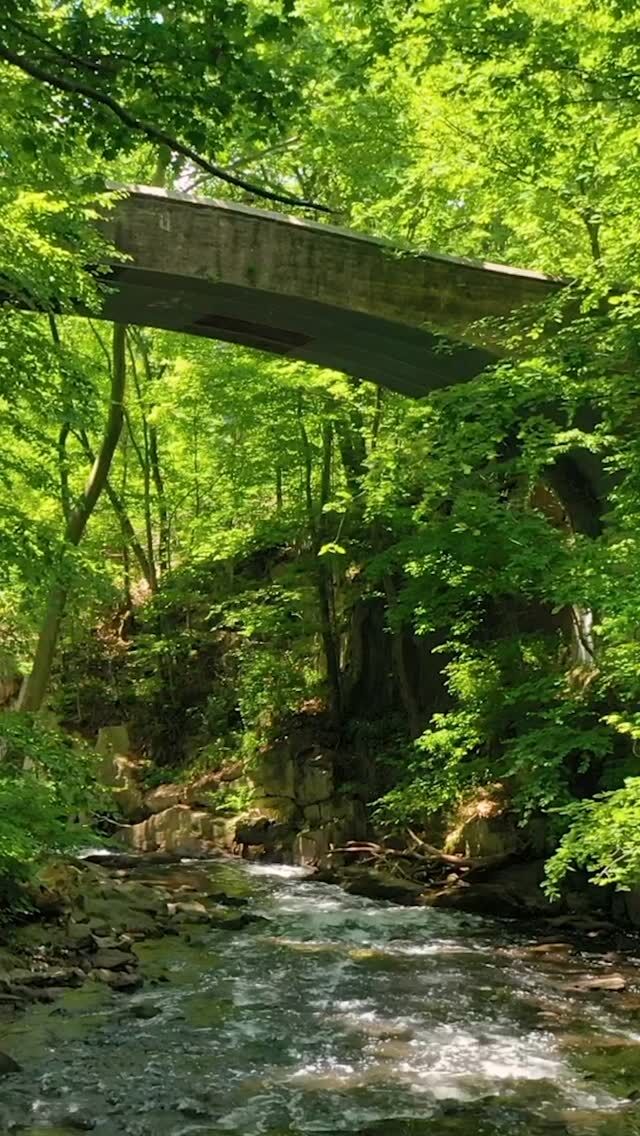

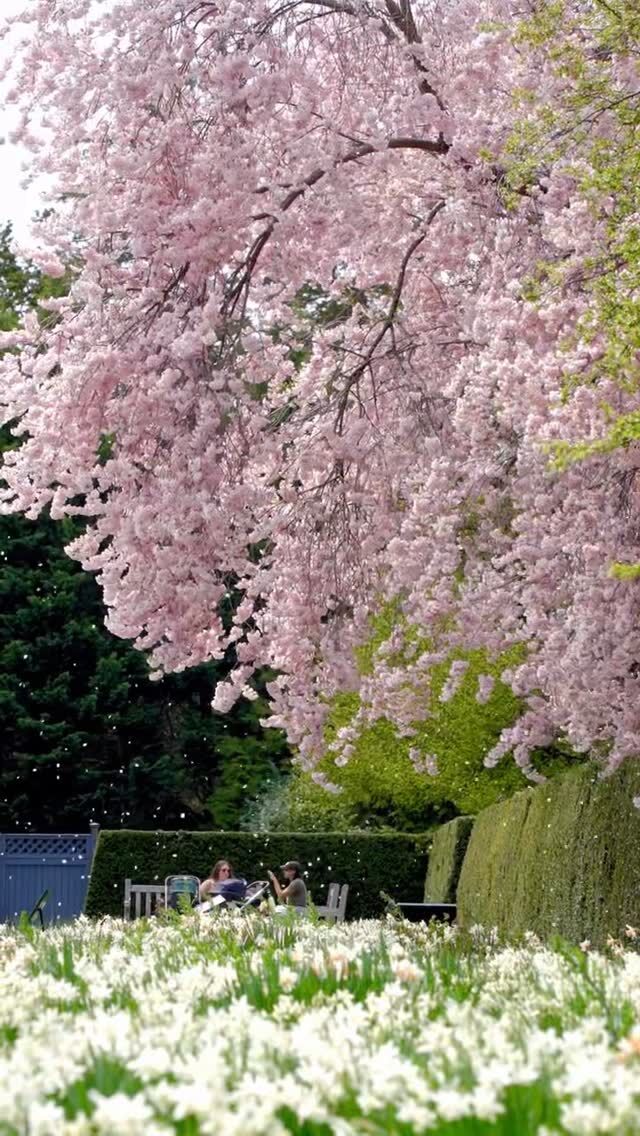

Numerous New York Botanical Garden staff members provided guidance and illustrations for this new edition, including images from historic collections of the LuEsther T. Mertz Library and photographs of NYBG’s living collections. In addition, there are many new photographs by the renowned plant photographer Steven Foster that add much to this third edition.

For more, listen to an interview with Dr. Balick about the new edition of the Handbook on the podcast A Way to Garden here.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.