Discovering the Art of ‘Flora Cubana’ in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library

Emily Sessions is a Mellon Fellow in the Humanities Institute of The New York Botanical Garden.

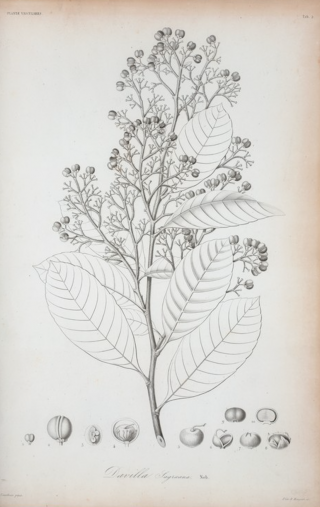

A botanical illustration by Ramon de la Sagre, genus Davilla

Since starting as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at the Garden’s Humanities Institute in September, I’ve worked almost entirely remotely, relying on the Garden’s excellent collection of digitized sources to continue my research into the intersection of science and political power in Cuba. From my apartment in Brooklyn, I’ve been able to examine a report written by the new director of Havana’s botanical garden in 1825; albums and field notes documenting Nathanial Lord and Elizabeth Knight Britton’s expeditions to Cuba in the first decades of the 20th century; and a beautiful set of photographs of Cuba created by Brother Marie-Victorin in the 1930s and ’40s.

Even though I feel lucky to have access to such a range of digitized sources, it was thrilling to get to visit the LuEsther T. Mertz Library for the first time in November, during an opportunity to explore the collections for research purposes with proper distancing, limited indoor capacity, and sanitization precautions. It was even more thrilling to get to see, during this visit, a little-known set of 100 botanical watercolors painted in Havana in the 1870s. Thanks to the excellent detective work of Susan Fraser, Director Emerita of the Mertz Library, and Samantha D’Acunto, Reference Librarian of the Mertz Library, I had the chance to become one of the few people in modern history to look closely at this fascinating set of paintings.

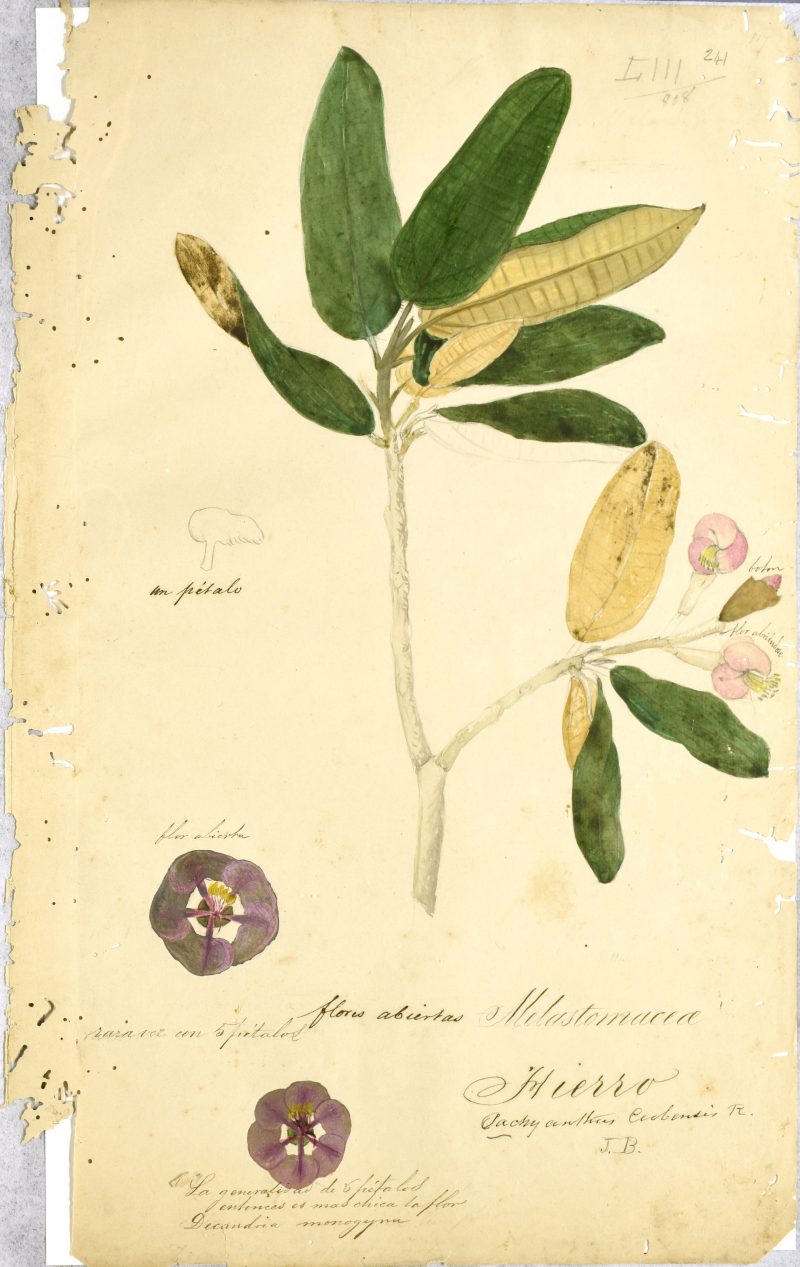

These watercolors were painted by Francisco Sauvalle (1807–1879), who was born in South Carolina to French parents but spent much of his botanical career in Cuba. They were intended to be used to produce an illustrated second edition of Sauvalle’s book Flora Cubana, which was first published in Havana in 1873. Unfortunately, they were never translated into printed illustrations, possibly due to Sauvalle’s death in 1879. These paintings, though, show an important scientist thinking through how to represent Cuban botany during a moment of intense political, social, and scientific change.

Francisco Sauvalle, untitled watercolor from planned illustrations for second edition of Flora Cubana, circa 1873-1879

The Spanish colony of Cuba placed sugar production, made possible by enslaved labor, at the center of its economy throughout the 19th century. At the moment that Sauvalle was painting these flowers and plants, however, emancipation was imminent—slavery officially ended in Cuba in 1880. Furthermore, the Ten Years War, the first of Cuba’s three Wars of Independence, lasted from 1868–1878. Finally, as I discuss in my dissertation, the previous decades were defined by intense debates about whether Cuban botany was best performed in Europe, where there was access to a wider range of scientific resources, or in Cuba itself, to prevent a loss of information when specimens traveled across the Atlantic.

As an art historian, I try to understand why artworks look the way that they do. Every time an artist created a representation, including a botanical illustration, they made specific artistic choices—about format, layout, visual emphasis, scale, and color, among other things. These choices, in turn, affected how the image worked—how audiences read the information that it contained.

Approaching the Flora Cubana illustrations from this perspective, the first thing that I noticed was that the watercolors in Sauvalle’s collection vary greatly in format. Some are quite sketchy, some highly detailed, some drawn in pencil only and others painted in full color. This is not entirely unusual for drawings that were meant to be turned into printed illustrations—many artists would include only the most cursory of details with the idea that the printmaker would fill in the rest based on this shorthand. Still, the wide variety of techniques that Sauvalle used in these Flora Cubana drawings might indicate that he was experimenting with how best to show these plants to international audiences.

Another quality that I noted about these drawings is that most show a specimen at life size, drawn without particular regard for symmetry on the page or for orderly placement of leaves or petals. This is quite different in format from, for example, Ramon de la Sagra’s Historia Física, Política y Natural de la Isla de Cuba, published some 30 years before. Sagra’s Historia included 69 illustrations of Cuban plants, each scaled so that the entire plant could fit on the page, each plant centered on this page and nearly symmetrical (see above), with a neat row of details arrayed along the bottom of the page. Sauvalle’s choice to instead depict plants at a 1:1 scale whenever possible, and without special emphasis on symmetry or a systematized format, makes his plants appear lifelike and individualized to the modern viewer. Sauvalle may have been thinking of other 19th century botanical artists who worked at 1:1 scale, such as Alexander Postels (1801–1871), whose Illustrationes algarum was published in St. Petersburg in 1840, or even Anna Atkins (1799–1871) and her celebrated cyanotype impressions, also of algae.

In fact, one of the most interesting aspects of this set is that many of Sauvalle’s watercolors seem to have been executed on top of a graphite rubbing from an actual specimen. The rubbed graphite traces of individual leaves and veins can be seen under many of Sauvalle’s pen and watercolor additions. This use of graphite rubbing to create an illustration is somewhat unusual—as anyone who has created a botanical painting might know, it would have been easier to draw a plant by hand than to build off of a graphite rubbing in this manner.

Why did Sauvalle make this artistic choice? Was it an attempt to make up for what he might have understood as his own lack of artistic training or ability? Was it meant to guarantee “accuracy” or “indexicality,” a link to an actual Cuban specimen during a moment of political change and debates about how much could be known about a distant land? Was it his attempt to save time or work more efficiently?

More research is needed into this fascinating set of watercolors to begin to answer these questions. I look forward, though, to hearing thoughts and responses from members of the Garden’s community and to spending the rest of my fellowship examining the Mertz Library’s rich collection of Cuban material.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.