Hispanic Heritage and Philippine Medicinal Plants: The Personal Story of Kathleen Cruz Gutierrez, Ph.D.

Kathleen Cruz Gutierrez, Ph.D., was a 2021–2022 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at The New York Botanical Garden. Stephen Sinon is the William B. O’Connor Curator of Special Collections, Research, and Archives in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library at The New York Botanical Garden.

This month the LuEsther T. Mertz Library honors Hispanic heritage with a look at the medicinal plants of the Philippines, which underwent Spanish colonization from 1521 to 1898. Kathleen Cruz Gutierrez, Ph.D., a 2021–2022 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in the Garden’s Humanities Institute, discusses her interest in the flora of her family’s homeland in conjunction with a display in the Mertz Library.

This month the LuEsther T. Mertz Library honors Hispanic heritage with a look at the medicinal plants of the Philippines, which underwent Spanish colonization from 1521 to 1898. Kathleen Cruz Gutierrez, Ph.D., a 2021–2022 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in the Garden’s Humanities Institute, discusses her interest in the flora of her family’s homeland in conjunction with a display in the Mertz Library.

The history of botany in the Philippines is a history of native expertise, competing empires, and political aspirations. Located on the edges of Asia and the Pacific, the Philippine archipelago is speculated to have the highest number of endemic species in the world.

My parents migrated to Los Angeles in the mid-1980s and I grew up in its historic Filipino enclave. One of the most pressing problems I experienced as a young person in my community was the absence of affordable healthcare. Inspired by a clinic that offers health services in Southeast Asian languages, I decided to pursue a career in public health.

I was encouraged to write my doctoral thesis on Philippine medicinal plants, an important facet of public health in rural areas. I began examining materia medica guides written in the immediate post-World War II period and during the Marcos dictatorship (1965–1986). Compilers of these texts positioned plants deeply in Philippine society’s historical contours. Continuing my research, I unearthed stories of field guides, illustrators, plant collectors, and patriots. What began as a science introduced by foreign-colonial agents became a field of collaboration, vernacular ingenuity, and political possibility.

Even more striking was discovering my own family’s ties to botany. Before leaving Manila in his early 50s, my father was a specialist in Philippine mahogany. Upon his arrival in America, he took a job at a trucking terminal and barely spoke of his former career in systematics. Recalling his past work, I asked him about botany while writing my thesis and our conversations on botany haven’t stopped since. As a 2021–2022 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in the Humanities Institute, I am presently completing my first book on the history of colonial botany in the Philippines.

Eduardo Quisumbing

I began my studies with this 1951 publication: Medicinal Plants of the Philippines by Eduardo Quisumbing. He came to meet and know Elmer D. Merrill, the second director of The New York Botanical Garden who had a near two-decade career in the archipelago soon after the start of U.S. colonization of the islands in 1898. Quisumbing’s introduction positions a future for Philippine science after the ravages of World War II.

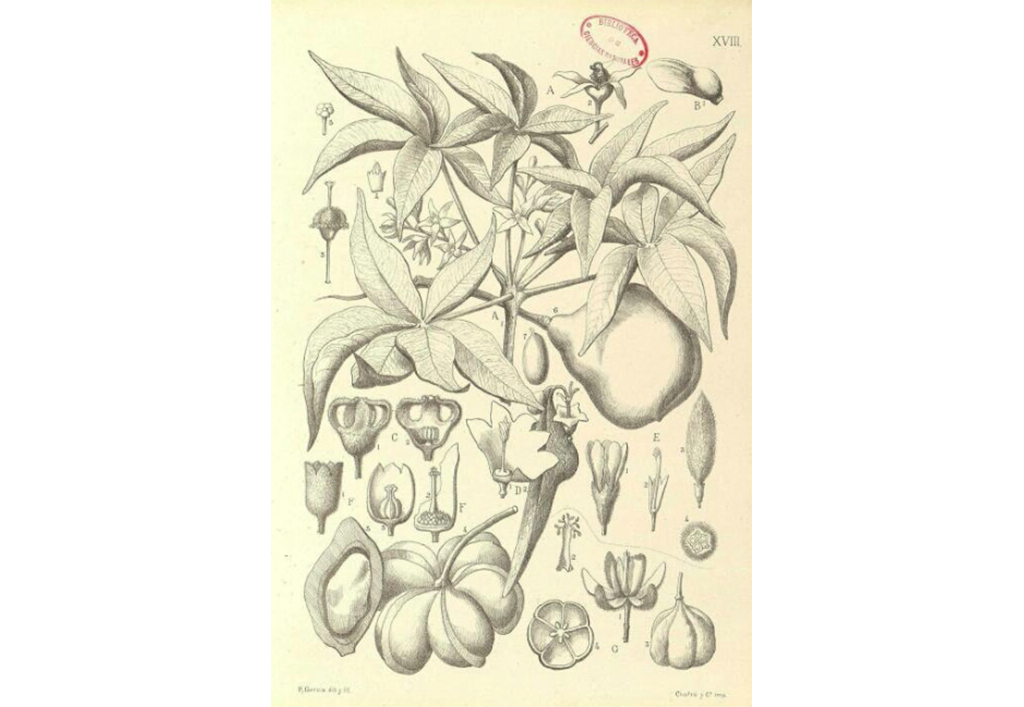

Quisumbing’s book inspired me to look back at the colonial underpinnings of botany. In my search, I came across Regino García y Baza, a Spanish-Tagalog painter born in Manila in 1845. A trained artist with a gift for oils and watercolor, he served as the sole illustrator of Sinopsis, one of the most significant botanical works on the Philippines produced in the late nineteenth century, and as the lead illustrator of the reissue of Flora de Filipinas. His artistic style broke visual conventions which can be seen through the use of shadowing, overlapping structures, and abundant forms arranged in a nonlinear fashion.

- “Diospyros embryopteris” (also known in Tagalog as kamagong or mabolo) in Flora de Filipinas ([1837] 1883), illustrated by Emina María Jackson y Zaragoza

- Image plate of Sinopsis de familias y géneros de plantas lenosas de Filipinas (1883), illustrated by Regino García y Baza

Emina “Emma” María Jackson y Zaragoza was born in 1858 into a very prominent family in colonial Manila. She married Catalán botanist Domingo Vidal y Soler, who traveled to the Philippines to enhance the Spanish colony’s botany operations. Vidal oversaw the publication of a reissue of the well-known Flora de Filipinas, originally published in 1837. Jackson likely developed her skills in painting through private study and alongside other prominent artist-naturalists in Manila, including Regino García. This plate is the only one in the reissue signed by Jackson–also referred to as “Emma Vidal”–and demonstrates elements of conventional botanical drawing that aided local and foreign readers’ conception of plant life in the Philippines.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.