Inside the Steere Herbarium: George Washington Carver and Grasses

Robert F.C. Naczi, Ph.D., is the Arthur J. Cronquist Curator of North American Botany in the Institute of Systematic Botany and Sergio Guzman is a Digitization Intern in the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium at The New York Botanical Garden.

George Washington Carver (1864?–1943) was a Black American who endured great hardship but achieved extraordinary accomplishments through his work as an agricultural scientist. Carver was born into slavery in Missouri and suffered poor health for much of his childhood. He spent most of his adult life in Alabama, pursuing his career at the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University). Carver’s achievements in agriculture are well documented. Less known are his accomplishments in multiple other fields, including mycology, floristics, and economic botany.

Carver began collecting herbarium specimens while attending Iowa State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University), where he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1894 and his master’s degree in 1896. It appears Carver began collecting herbarium specimens in 1893 while he was an undergraduate; these early specimens were both fungi and flowering plants.

Due to extensive study, Carver’s fungal specimens are relatively well-known, most of which are plant pathogens. NYBG’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium is an important repository of Carver’s fungal collections, perhaps the largest single collection of his fungi.

What is much less known, however, is Carver’s love of grasses (Poaceae). Among flowering plants, he appears to have collected far more grasses than any other family. The Iowa State University Herbarium houses 115 specimens of 70 grass species collected by Carver from many localities in Iowa during 1893–1897, mostly during his student days. The grasses he collected include generalists that grow in a wide range of habitats, some quite weedy, and specialists that are much more particular in their growing conditions. Carver visited such varied habitats as dry prairies, marshes, wet mudflats, and forests in his pursuit of grasses.

A grant from the National Science Foundation’s Advancing Digitization of Biodiversity Collections program enabled all North American grasses in the Steere Herbarium to be digitized. This was a huge accomplishment: 91,809 grass specimens made accessible online within the five-year project (2011–2016). At NYBG, the priorities for specimen digitization are photography of specimens and then posting these images online. The advantage of this strategy is maximization of specimens available online, but the downside is image-only specimens cannot be directly searched by the public based on collection data. Making collection data accessible online entails added steps of entering the specimen label information in a database, typically at least locality, date, and collector name.

During the era in which Carver collected, it was common practice when collecting to gather several specimens per species and send the duplicates to other herbaria with the expectation of receiving specimens in return. Similarly, specimen exchange is common today because it is so beneficial to advancing botanical knowledge and making herbarium collections more informative and representative. Realizing Carver collected many grasses and specimen exchange was prevalent, we wondered how many of his grass specimens and which species might be in the Steere Herbarium. Search in NYBG’s C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium revealed one grass specimen: Purple Lovegrass (Eragrostis spectabilis). Surely, we thought, more of Carver’s grasses must be in the Steere Herbarium.

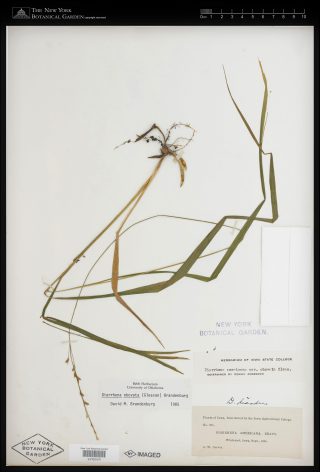

Fig. 1 Digitized specimen of Carver’s Diarrhena obovata from NYBG’s Steere Herbarium.

To test this expectation, Rob chose five other grass species Carver collected and searched the Herbarium holdings. He found one of Carver’s specimens: Obovate Beakgrain (Diarrhena obovata), a beautiful grass with deep-green leaves that grows in colonies in forests, often on floodplains.

With this encouraging result, Rob was preparing to look for more of Carver’s grass specimens. Sergio suggested using OCR (optical character recognition) to speed the process. OCR is a computer-driven method that recognizes text within images and converts the text to a searchable form. Since we have images for all North American grass specimens in the Steere Herbarium, it would allow us to find more of Carver’s grass specimens and save us valuable time (no need to physically search through folders of specimens).

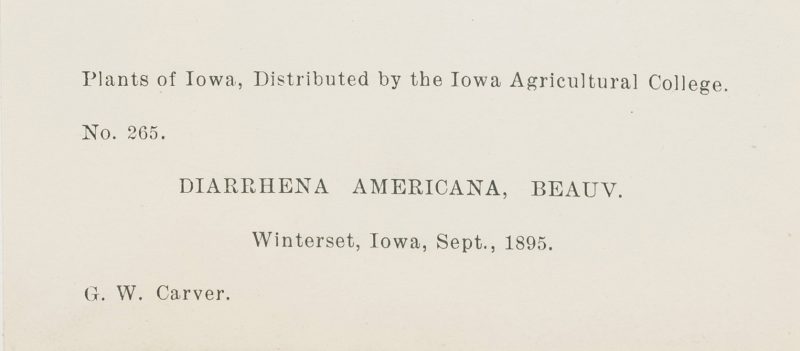

Fig. 2 Collecting label from Carver’s Diarrhena obovata specimen. Revision of this species’ classification subsequent to Carver’s collection has changed its identification.

Sergio’s OCR work was the breakthrough we needed! He performed OCR on the entire set of North American Poaceae specimens. Only three minutes later, we had our answer: four Carver grass specimens, including two that we had not yet found: One-sided Wheatgrass (Elymus trachycaulus) and Western Wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii). Both of these grasses usually grow in sunny places such as meadows and prairies.

Fig. 3 Plants of Diarrhena obovata growing in the wild, ©Peter M. Dziuk, Minnesota Wildflowers, www.minnesotawildflowers.info

What do we learn about Carver from his grass specimens? His multiple collecting trips over the span of five years reveal a deep interest in the Grass Family. The preponderance of collections from the summer are understandable for a student with a challenging academic schedule and one who knew how to manage his time well to maximize productivity. His successes in finding and documenting so many species reveal that Carver was a keen observer and hard-working collector. His exploration of many habitats makes it clear that he loved nature.

Carver collected plants from at least a few other families than grasses. Once the entirety of the Steere Herbarium is digitized, it will be possible to find all of his specimens at NYBG. We expect the Steere Herbarium has more specimens collected by this innovative and influential scientist who contributed so much to the advancement of botanical knowledge through his study of plants and fungi.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.