Learning from the Wind in the Pacific Islands of Melanesia

Michael J. Balick, Ph.D., is Vice President for Botanical Science and Director and Senior Philecology Curator of the Center for Plants, People, and Culture at The New York Botanical Garden (NYBG); K. David Harrison, Ph.D., of VinUniversity in Hanoi, Vietnam, is an NYBG Affiliate Scientist; and Gregory M. Plunkett, Ph.D. is Senior Curator, Center for Plants, People and Culture.

Outdoors, the natural movement of air that we can feel is known as wind. Wind blows from different directions, and for the most part, we don’t consider that it has meaning or consequence, unless an intense storm kicks up. Yet wind plays an important role in Earth’s environment as what has been called “the great equalizer” of the atmosphere, transporting heat, moisture, dust, and pollutants around the globe, and in recent years, it has become an increasingly important source of renewable energy.

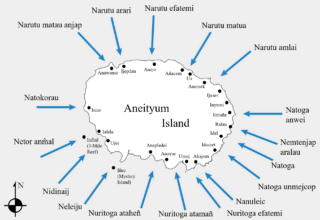

Named winds on Aneityum, with geographical anchors (locations of place names from Anejo to Inyerei are approximate)

On the remote archipelago of Vanuatu, however, people have a different sense of the wind, especially older people who still recall a set of knowledge known as “wind lore.” The three of us, along with Neal Kelso, Dominik and Nadine Ramík, and Martial Wahe, recently published a paper titled “Wind Lore as Environmental Knowledge in Southern Vanuatu” in the Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, where we address this topic.

Most such studies of wind focus on identifying wind patterns related to long-distance navigation—for example, keeping the wind at your back when you sail your voyaging canoe to a specific destination. Use of these patterns in the Pacific was referred to as wind compasses by Europeans, and observations date as far back as the early 18th Century, when a Jesuit priest wrote about the crew of a vessel that had drifted to Guam from Faraulep Atoll in the central Caroline Islands. As explained to him by the crew, they used their wind-guided routes to arrive at their destination.

Our current paper is one of the first examples of scientific research that includes land-based perspectives on wind, for example, its use in agriculture and crafts. On Aneityum Island, there are 17 different named winds listed by Pascal Nañak and Joel Simo of Imtaña village, with the Narutu winds indicating that it is a good time to weave mats as the leaves that are used are pliable and easy to work with. Other winds, such as Natoga, are a sign that it is a good time to plant gardens. Our colleague who lives on this same island, Tony Keith, recently commented that there are more than the 17 recognized winds that our study identified, but that local people had forgotten the names and meanings.

In other parts of southern Vanuatu, winds are known to signal the dry weather that causes taro leaves to dry out and their tubers to shrink, indicating that it is a good time to harvest this essential food. Wind lore helps to guide hunting, fishing, foraging, and agricultural practices in this part of the world. Sadly, as cultural memory disappears, the environmental and social resilience of traditional cultures that have documented and depended on this knowledge for hundreds of years or more is also reduced.

The full research paper is available here.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.