LuEsther T. Mertz Library Book of the Month: Chinoiserie Botany

Stephen Sinon is the William B. O’Connor Curator of Special Collections, Research and Archives, at the LuEsther T. Mertz Library of The New York Botanical Garden.

Born in Metz, France, naturalist and artist Pierre Joseph Buc’hoz (1731–1807) become a doctor of medicine in Nancy in 1763. In his medical practice, he focused on the treatment of depression wherein he recommended music as therapy. He was a successful physician counting among his patients many prominent individuals, including the King of Poland and the brother of the King of France, the future King Charles X.

Born in Metz, France, naturalist and artist Pierre Joseph Buc’hoz (1731–1807) become a doctor of medicine in Nancy in 1763. In his medical practice, he focused on the treatment of depression wherein he recommended music as therapy. He was a successful physician counting among his patients many prominent individuals, including the King of Poland and the brother of the King of France, the future King Charles X.

He became interested in the study of many disciplines in the natural sciences. He travelled throughout his native Lorraine and published a 13-volume natural history of the province. Teaching botany as well as medicine, he was a demonstrator at the Royal College of Medicine in Nancy.

The second half of the 18th century experienced a growth in natural history publications in France, concurrent with the publication of Buffon’s monumental and lavishly illustrated 44-volume Histoire Naturelle between 1749 and 1804. The accession of Louis XVI to the throne in 1774 was followed by a relaxation in the book trade regulations, making it easier for authors to publish their own works.

Buc’hoz became an enthusiastic and prolific publisher of many lavishly illustrated folio works in the natural sciences, including botany, minerology, animals, and in particular birds. His output was prolific due in part to his habit of appropriating designs from his contemporaries, as well as adapting his own text and illustrations for re-use among his numerous publications. The print runs for his publications were small, such that many of them remain rare even today.

Of the more than 300 works published by Buc’hoz, many are full of errors. His descriptions and figures were often inaccurate and most naturalists refused to cite his works or accept any of his scientific names. While some of his publications were appealingly decorative, they did little to advance scientific knowledge.

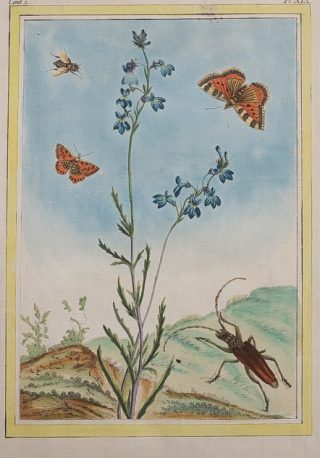

In the year 1776, he published a two-volume folio entitled Collection precieuse et enluminee des fleurs… featuring 200 hand-colored plates. The first hundred plates depict Chinese plants growing in Chinese gardens—79 of these plates have captions written in Chinese. Although the text does not indicate their origin, they are certainly by the hand of a Chinese artist. This publication is therefore credited as being the first western publication to feature the work of native Chinese artists. The highly decorative plates depict compositions of native Chinese plants accompanied by birds, butterflies, insects, and rodents set against pale blue skies and often featuring gongshi, or scholars’ rocks.

While the Chinese influence can be seen in the second hundred plates as well, these were created by European artists and depict plants from European gardens which included plants from Africa and the Americas. These plates represent the earliest examples of western artists purposely copying the style of the Chinese.

While the Chinese influence can be seen in the second hundred plates as well, these were created by European artists and depict plants from European gardens which included plants from Africa and the Americas. These plates represent the earliest examples of western artists purposely copying the style of the Chinese.

Buc’hoz found a ready market for this work not only among his fellow naturalists and painters, but also among porcelain, silver, and textile manufacturers. The “Chinoiserie” style was quite fashionable throughout European decorative art and architecture in the mid-18th century and was noted for its purposeful imitation and mixing of a wide range of Asian artistic styles.

While Buc’hoz was much criticized in the 19th century for his enormous output and lack of scientific exactitude, he was a respected member of many European scientific academies, and there is no disputing that these engravings are among the finest of their time. They are especially notable for their attention to color and detail, however it should be noted that all of the plates were colored by European hands without having seen any of the original specimens depicted. The Chinese plant plates therefore often feature fanciful color combinations, as many of these were yet unknown in the west.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.