“Mournful Relics” through Foreign Eyes: Envisioning Land Degradation on Nineteenth-Century Brazilian Coffee Fazendas

Caroline L. Gillaspie is a 2020 CUNY-NYBG Fellow and a Ph.D. Candidate in the Art History department at the CUNY Graduate Center.

[Untitled Study of Coffee Specimen], 1872, Frontispiece from Robert Hewitt, Jr., Coffee: Its History, Cultivation, and Uses (New York: Appleton and Company, 1872)

In 2020, we have been forcefully confronted by our present day existential crises that have dominated the news cycles—a global pandemic, as well as the effects of contemporary climate change. While diligently completing my fellowship remotely at the NYBG, my attention was drawn toward reports about Covid-19, the massive fires on the west coast of the United States, and the powerful Hurricane Laura making landfall on the Gulf coast. Over a year ago now, photos of São Paulo, Brazil, blanketed in smoke, dark as night even during midday had filled my newsfeed. Yet still today, devastating fires in the Amazon rainforest, initially ignited to clear land for cattle ranching, continue to rage. Such reports weighed on my mind as I spent this summer examining nineteenth-century texts that described the slash-and-burn method of clearing forested land for coffee farms, that lamented the droughts caused by the removal of tree cover, and that feared for the survival of Brazil’s coffee industry as irregular but torrential rainfall eroded the soil.

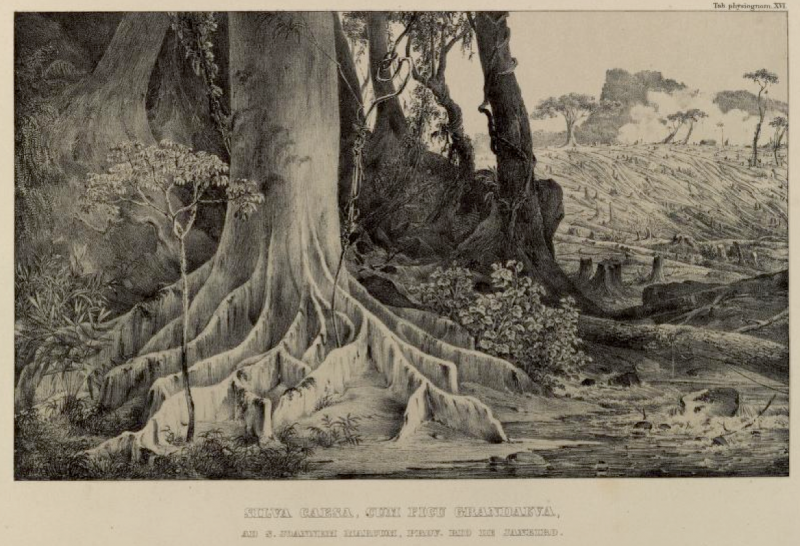

The lithographic print Silva Caesa, Cum Ficu Grandaeva directly references the large-scale deforestation that took place in the nineteenth century in preparation for agricultural fields. The print was published in the first of 40 volumes of Flora Brasiliensis by German botanist Karl Friedrich Phillipp von Martius. This image features a striking juxtaposition between monumental wilderness and environmental destruction caused by human industry. An impressive focal point to this composition is the massive root system that emerges from a thick tree trunk to snake its way toward the viewer, creating a powerful foundation that stabilizes the aged tree. The Brazilian landscape of the foreground appears enormous and ancient, enlivened as roots and vines writhe and wrap their way up tree trunks and a cascade of fresh water spills into a rocky stream. A fallen tree lying across the stream separates this fascinating wilderness scene from the desolation of the background. Ax-cut stumps and fallen tree trunks are scattered across the hillside as laborers (most likely enslaved) are tasked with cutting into the few trees left standing. A billow of smoke rises in the far distance as the workers burn the felled trees. During his three years of travel in Brazil between 1817 and 1820, von Martius witnessed the clearing of land for a variety of crops, including coffee, cotton, sugar, and manioc. He describes in Flora Brasiliensis the “glorious nature and the magnitude of the sublime” he saw in Brazil, and at the same time the insatiable desire of humans to make use of this land, leaving nothing untouched.

Silva Caesa, Cum Ficu Grandaeva, ad S. Joannen Marcum, Prov. Rio de Janeiro, c. 1842, Plate XVI from Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius, Flora Brasiliensis, enumeratio plantarum in Brasilia hactenus detectarum, vol. 1, part 1 (Munich: R. Oldenbourg, 1840-1857)

The process of cutting and burning forests quickly cleared land on hillsides that would be used for planting coffee bushes. Such agricultural methods rejected the cabruca system of interplanting in which crops are planted between existing trees. This agroforestry system was used in Brazil’s Amazon region by indigenous peoples for the cultivation of cacao, and later in the province of Bahia. I thank Dr. Douglas Daly of the NYBG for (among many other things) raising this important contrast, as the later coffee industry of the nineteenth century largely rejected this indigenous knowledge of agricultural management in favor of hasty and far more destructive solutions. With the coffee industry’s rapid rise in Brazil, particularly after independence in 1822, more and more land in the mountainous region of Rio de Janeiro was claimed for expanding coffee fazendas. Two decades later, the artist Félix Emile Taunay (1795-1881) lamented ecological damage in Rio de Janeiro in his catalogue entry for the Imperial Academy’s General Exhibition of 1842. He wrote, “According to irrefutable calculations, the vanishing of the finest specimens of the plant kingdom from the outskirts of the City [of Rio de Janeiro] threatens the latter with diminished flow of water and higher average levels of heat, two reciprocally active evils.”

The mountains within the province of Rio de Janeiro provided the ideal conditions for coffee cultivation, which soon after expanded to Minas Gerais and São Paulo. The rich argillic soil, referred to in Portuguese as terra roxa for its reddish color, combined with milder climate, moderate rainfall, and elevated altitude allowed for successful coffee growing. The photographer Louis Agassiz, who journeyed through Brazil in the 1860s, noted the expanse of coffee plantations across land previously occupied by “primeval forest,” and the quality of soil on which they were established. He stated, “Thanks to their perseverance and the favorable conditions presented by the constitution of their soil, the Brazilians have obtained a sort of monopoly on coffee.”

Nineteenth-century prints and paintings of coffee fazendas often note these favorable conditions while avoiding reference to the environmental consequences of the coffee industry. Published in Johann Jacob Steinmann’s (1800-1844) travel book, the hand-colored lithograph Plantação de Café features a small productive coffee fazenda in the province of Rio de Janeiro. Visible are orderly rows of coffee bushes lining the hillsides, mountains implying altitude, glowing light and some clouds optimistically suggesting moderate weather and climate, and small streams providing water for the processing of harvested coffee berries. The tamed and cultivated fields are distinct from the wildly growing trees at the left of the composition and the sprawling landscape of rugged mountains extending into the distance. Unfortunately, due to widespread deforestation performed for coffee fazendas, waterways evaporated more quickly, leading to drought, shifting rainfall patterns, and unstable temperatures. Rather than regular, moderate rainfall that benefited coffee cultivation, rains became less frequent but heavier. Torrential downpours washed through the bare channels between carefully spaced out coffee bushes, stripping the land of rich topsoil.

Friedrich Salathé, Plantação de Café, 1835-1839, from Johann Jacob Steinmann, Souvenirs de Rio de Janeiro (Basel, Switzerland: J. Steinmann], 1835-1839).

For the past several months, as the world seemed to be both literally and figuratively on fire, I contemplated images of burnt forests, bare hillsides, eroded soil, and enslaved laborers. Culled from the collection of the Mertz Library and Biodiversity Heritage Library, I read nineteenth-century descriptions of the science behind coffee cultivation, the ecological consequences of such agricultural methods, and the fears about losing an industry that fueled a young nation. I considered artworks that celebrated the coffee industry and denied the climate change and degradation that it caused, and worked to contextualize them within this environmental history. During this summer of struggle, as we all have been quarantined and forced to perform tasks remotely while avoiding the distractions of the news, I remain sincerely grateful for the assistance of the staff at the New York Botanical Garden, LuEsther T. Mertz Library, and the Humanities Institute. In particular, I am thankful for the supportive and thought-provoking discussions with Humanities Institute Director, Vanessa Sellers, and Reference Librarian, Samantha D’Acunto, and the rich resources compiled by Samantha. I am also deeply appreciative of consultations with NYBG scientists Dr. Douglas Daly and Dr. Andrew Henderson, Conservation Librarian Olga Marder, and former NYBG fellow Dr. Tim Lorek. Like all researchers in the present moment, a challenge during this fellowship was access to materials. But thanks to digital material compiled by Samantha, and guidance from staff on scientific topics that initially seemed far beyond my grasp as an art historian, I am better equipped to examine the visual culture of coffee cultivation in nineteenth-century Brazil.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.