NYBG and Some Remnants of the Second World War

Zachary Rosalinsky is the Special Collections Catalog Librarian in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library of the New York Botanical Garden.

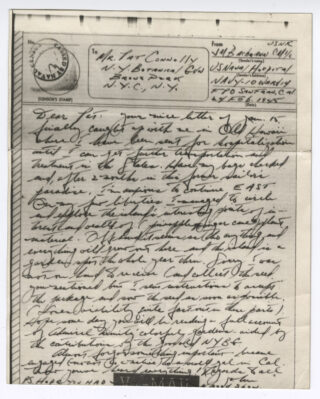

A piece of V-Mail sent on February 24, 1945 by John Martin Bachmann III, a Carpenter’s Mate 1st Class in the U.S. Naval Reserve, to Pat Connolly, foreman of range 1 in NYBG’s Haupt Conservatory.

As the Special Collections Catalog Librarian at the New York Botanical Garden’s LuEsther T. Mertz Library, I encounter a great many small pieces of history that, when put together, tell a much larger story. This happened recently when I cataloged a small (just 14 x 11 cm) document from 1945 out of the Mertz Library Archive’s Small Collections. The Archives Small Collections are a gathering of manuscripts—mostly letters—that are too varied to get their own collection designation, so we keep them together as one large miscellany. The items get individual cataloging, so they and their contents are findable in the Mertz online catalog.

This document in particular is a piece of V-mail, or Victory mail, which was a means of managing post sent by American soldiers back to the mainland United States during World War II. In an effort to reduce the cost of sending letters home, V-mail letters were written on 23.2 x 17.8 cm paper, censored by the military, copied to film, and sent to one of three postal centers in the continental United States: New York, San Francisco, and Chicago, each of which processed the V-mail for its home region. The mail would be printed on paper that was 60% of the size of the original letter at its destination and finally delivered to the recipient. This process saved shipping costs and also conserved thousands of tons of much-needed airplane cargo space. V-mail also had the advantage of countering espionage attempts, as the photocopy process did not reproduce invisible ink, microdots, or microprinting. The American V-mail technique was adapted from British Airgraphs, a similar process invented by the Eastman Kodak Company in 1930. Though V-mail was only implemented by the U.S. military between June 1942 and November 1945, over 1 billion letters were processed during that time.

Our copy of V-mail was sent on February 24, 1945 by John Martin Bachmann III, a Carpenter’s Mate 1st Class in the U.S. Naval Reserve, to Pat Connolly, who by this point was the foreman of range 1 in the NYBG Conservatory, after having earlier been T.H. Everett’s assistant in the Horticulture department. In the letter, Bachmann notifies Connolly that he has been hospitalized in Hawaii, from which place he will be sent to the continental United States for further treatment. Indeed, when the letter is finally sent, it comes from the naval hospital in San Francisco. Bachmann notes that he has had a chance to explore the flora of Hawaii while he was there. Connolly apparently sent Bachmann a seed, which Bachmann was unable to get, but which he hopes to sow as soon as he can. Bachmann is hoping Connolly will see Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s “colorful gardens aided by contributions of the good old NYBG.”

Our copy of V-mail was sent on February 24, 1945 by John Martin Bachmann III, a Carpenter’s Mate 1st Class in the U.S. Naval Reserve, to Pat Connolly, who by this point was the foreman of range 1 in the NYBG Conservatory, after having earlier been T.H. Everett’s assistant in the Horticulture department. In the letter, Bachmann notifies Connolly that he has been hospitalized in Hawaii, from which place he will be sent to the continental United States for further treatment. Indeed, when the letter is finally sent, it comes from the naval hospital in San Francisco. Bachmann notes that he has had a chance to explore the flora of Hawaii while he was there. Connolly apparently sent Bachmann a seed, which Bachmann was unable to get, but which he hopes to sow as soon as he can. Bachmann is hoping Connolly will see Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s “colorful gardens aided by contributions of the good old NYBG.”

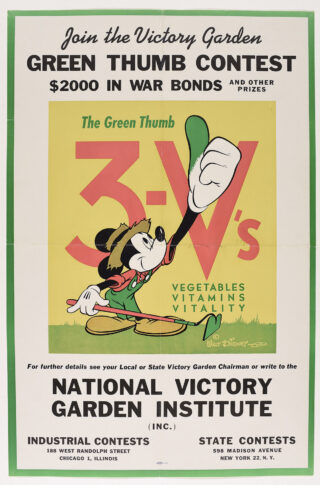

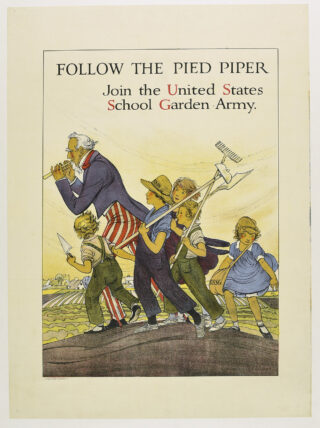

This V-mail is not the only vestige of the Second World War housed at the Mertz Library. We also house a collection of victory garden posters. The victory garden, which the government encouraged during the First and Second World Wars, was a gardening project in which Americans grew their own seeds at private residences and in public parks to make the scarcity of the war years easier to bear. Vegetables were needed for the U.S. troops and the government needed to keep food prices down. Around one third of the vegetables produced by the United States during World War II came from victory gardens and, at their peak, there were more than 20 million victory gardens in the United States. NYBG has some fine examples of posters from this period, including several featuring patriotic characters and one poster, copyrighted by Walt Disney in about 1944, which depicts Mickey Mouse and advertises a victory garden vegetable growing contest, the first prize for which was $2,000 in war bonds.

This V-mail is not the only vestige of the Second World War housed at the Mertz Library. We also house a collection of victory garden posters. The victory garden, which the government encouraged during the First and Second World Wars, was a gardening project in which Americans grew their own seeds at private residences and in public parks to make the scarcity of the war years easier to bear. Vegetables were needed for the U.S. troops and the government needed to keep food prices down. Around one third of the vegetables produced by the United States during World War II came from victory gardens and, at their peak, there were more than 20 million victory gardens in the United States. NYBG has some fine examples of posters from this period, including several featuring patriotic characters and one poster, copyrighted by Walt Disney in about 1944, which depicts Mickey Mouse and advertises a victory garden vegetable growing contest, the first prize for which was $2,000 in war bonds.

Using plants to reckon with the horrors of war has long been a special project for the New York Botanical Garden. In 1919, a grove of 150 Douglas-fir trees (Pseudotsuga menziesii) were planted as a living memorial to the American soldiers lost in the recently ended First World War, among whose ranks numbered almost 14,000 from New York; the money for the trees was raised with community donations. These plants are still a part of the NYBG living collections, being located just south of Daffodil Hill.

Also after World War I, a program was put in place to train disabled and convalescent American soldiers and sailors in the gardening profession. There were not many young men interested in the gardening profession, and so this program was a mutually beneficial arrangement, replenishing the horticultural workforce and providing returning soldiers with a profession even if they had suffered injuries in the war. Training included such practical matters as potting, washing plants, caring for and potting orchids and ferns, pruning, watering, and maintaining greenhouses. These future gardeners were trained to grow flowers, vegetables, and other plants desired by those for whom they might someday work. The legacy of this outstanding and important work continues to this day with the Therapeutic Horticulture and Rehabilitative Interventions for Veteran Engagement (THRIVE) program, begun in 2019, which combines horticultural therapy and gardening activities to help veterans heal both physically and mentally.

Also after World War I, a program was put in place to train disabled and convalescent American soldiers and sailors in the gardening profession. There were not many young men interested in the gardening profession, and so this program was a mutually beneficial arrangement, replenishing the horticultural workforce and providing returning soldiers with a profession even if they had suffered injuries in the war. Training included such practical matters as potting, washing plants, caring for and potting orchids and ferns, pruning, watering, and maintaining greenhouses. These future gardeners were trained to grow flowers, vegetables, and other plants desired by those for whom they might someday work. The legacy of this outstanding and important work continues to this day with the Therapeutic Horticulture and Rehabilitative Interventions for Veteran Engagement (THRIVE) program, begun in 2019, which combines horticultural therapy and gardening activities to help veterans heal both physically and mentally.

There are so many little-known relics of the past housed at the LuEsther T. Mertz Library just waiting to be discovered. From rare books to manuscripts to botanical art and beyond, there are an almost limitless variety of things to learn about botany, horticulture, history, and more.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.