Painting the Rose Garden: A Conversation with James Gurney

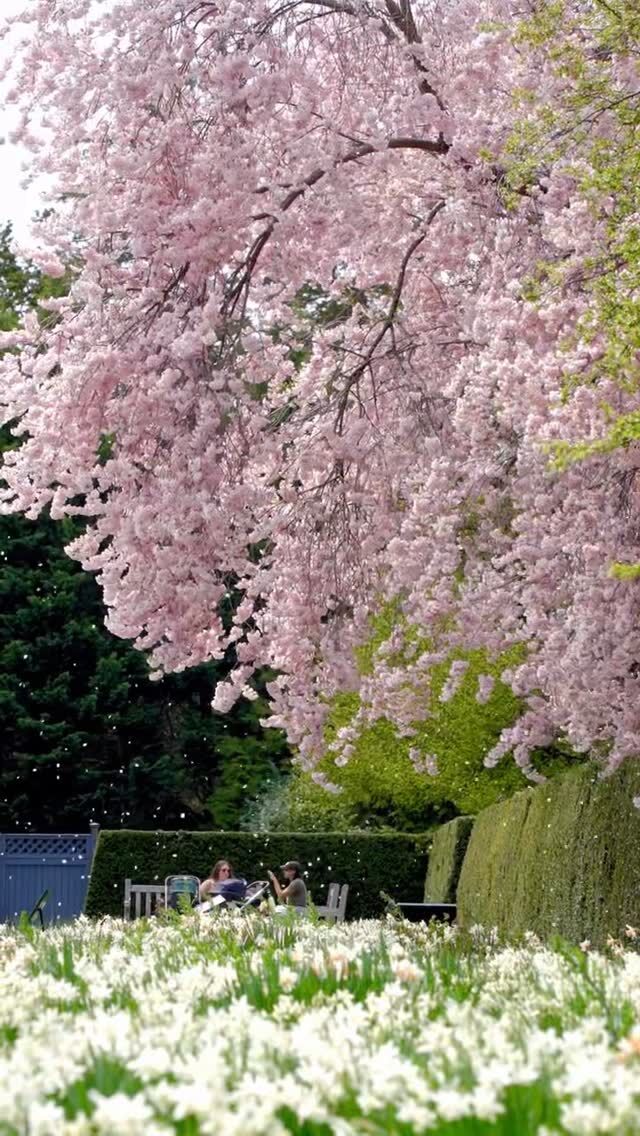

Longtime plein-air painter and friend of the Garden James Gurney has guided and inspired many artists, as well as visitors, through NYBG’s annual Plein-Air Invitational. Though this year’s Invitational has been cancelled, Gurney shares his methods and stories with us in the video below, which was filmed in the Peggy Rockefeller Rose Garden in June of 2016. The footage transports us to a glorious spring day in the Rose Garden, and the following conversation with Gurney illuminates his personal relationship with plein-air painting and provides suggestions for those who wish to pick up a paint brush and create interpretations of their natural surroundings.

HLB: How did you come to have an interest in plein-air painting?

JG: I caught the bug for on-the-spot sketching about 40 years ago, before people started calling it “plein-air painting.” I decided to take a summer off from art school and never came back, because I was learning more painting from life. Along with a good artist friend, we loaded our backpacks with art supplies and jumped onto an open boxcar eastbound from the L.A. freight yards. All that summer, my friend and I slept in graveyards and on rooftops and sketched portraits of gravestone cutters and lumberjacks.

To make money we drew two-dollar portraits in bars by the light of cigarette machines. By the time we got to Manhattan, we had a crazy idea to write a how-to book on sketching. We hammered out the basic plan for the book on Burger King placemats. By night we slept on abandoned piers and by day we made the rounds of the publishers. We eventually got a contract from Watson-Guptill, who published The Artist’s Guide to Sketching in 1982. My friend and coauthor was Thomas Kinkade, before he became known as the “Painter of Light.”

HLB: In your opinion, what makes plein-air painting so special?

JG: I like interpreting the world around me with no filter. It’s just me and my little book and my handful of pigments trying to make intelligible the whirling chaos of reality. As artists it’s hard not to fall back on conventional approaches, but sketching from life helps me discard my expectations about what an “artistic” subject ought to look like.

I try to find something beautiful in a subject that most of us overlook, such as a supermarket doorway or a jet airplane parked at the airport. This inclination sometimes makes me feel ill at ease in places with such obvious beauty and lushness as a garden, because the tradition is so strong, and the standards have been set so high by garden painters such as George Elgood or Mildred Butler.

HLB: Do you have a favorite flower to paint, and why?

JG: One year in the Garden I fell in love with a small group of cleomes, or spider flowers. They were tucked away in the Family Garden. I used an old-fashioned paint called casein, which was popular before acrylic was developed. I was fascinated by the shape contrast between the oval petals and the long, filament-like stamens. I love the way the leaves get smaller and yellower as you go up the stem. You don’t see paintings of cleomes as often as other flowers, but to me they just call out to be painted, because they make such a beautiful silhouette, and they seem so delicate.

HLB: Which NYBG collection is your favorite to capture?

JG: I know roses are the popular favorite, and they’re my favorite, too. There’s so much richness of form and color from an artist’s perspective. And of course on a warm summer day the scent is heavenly, the people are friendly, and there’s a painting just begging to be captured anywhere you look. In the included video I’m painting the variety called “Carefree Beauty.” I’m close enough to see the structure of individual flowers and leaves, but far enough away to allow the individual flowers to group into masses.

What amazes me with roses on a warm day is how much the blossoms change from the morning to the late afternoon. If your painting shows the particular shape of specific blossoms, they will change drastically by the time the session is over, and if you return the next day hoping to find the same arrangement, it won’t be there. Seeing plants in the dimension of slow time is a huge revelation.

HLB: What does the NYBG Plein-Air Invitational mean to you?

JG: When I think of each of the years we’ve done it, I recall the feeling of camaraderie and common purpose shared by a group of friends, each of us trying to carve a slice of the magic that is NYBG. After weeks of anticipation we head out to our chosen spot on a golf cart. As we paint, it’s a chance to meet members of NYBG’s loyal public, many of whom have artistic inclinations of their own. At the end of a busy day of painting, we gather to munch on treats, sip wine, share our tales of triumph and disaster, and check out what each of us created.

HLB: Which seasonal collection do you look forward to painting in the future?

JG: I want to get back to painting the lilacs again. The aroma is heavenly, the variety of colors and types are incredible, and I appreciate being allowed to set up our easels on the grass around them. While studying the lilac flowers, it’s fun to watch the bees busy at their work. I love the way the flowers start out as bulbous buds, each with a tiny “X” at the tip, and the way they open into four-petaled flowers, starting at the base of the spike.

HLB: What is the most challenging aspect of the art?

JG: I’m always fascinated and challenged by the way petals of hollyhock, roses, and peonies can focus and intensify color in the center of the blossom. Nobody described the artistic effect better than Gertrude Jekyll:

“Some of the colour is transmitted through the half-transparency of the petal’s structure, some is reflected from the neighbouring folds; the light striking back and forth with infinitely beautiful trick and playful variation, so that some inner regions of the heart of a rosy flower, obeying the mysterious agencies of sunlight, texture and local colour, may tell upon the eye as pure scarlet; while the wide outer petal, in itself generally rather lighter in colour, with its slightly waved surface and gently frilled edge, plays the game of give and take with light and tint in quite other, but always delightful, ways.”

HLB: As a longtime plein-air artist, have you noticed any significant changes in the environment that affect your work? Do you have any examples?

JG: I live in the mid-Hudson Valley, and I’ve noticed the effects of invasive plants such as Japanese stiltgrass in the understory, and I’ve certainly noticed the effects of the big die-off of pine forests when painting mountain landscapes in Colorado. During this recent lockdown period, I’ve noticed some encouraging signs of nature bouncing back, with far more native wildflowers, such as trillium, in our local forest. I don’t know why they haven’t been browsed by the deer, but I appreciate seeing them again.

HLB: What tips do you have for budding plein-air artists?

JG: I would suggest that young artists who want to paint from life should always keep a sketchbook for pencil sketches and quick color studies. Building up a practice of regular sketching excursions with friends is a great way to get started. There are Urban Sketchers groups and plein-air meetups in almost every city. Every once in a while I think it’s important to slow down and spend more than one session on a work of plein-air, perhaps at least three or four hours on one study. And you don’t have to do it in a busy, public location if you’re nervous about people watching or judging you.

Look for non-touristy places where artists rarely go, and where no one would expect to find someone painting. You’ll have it all to yourself and you’ll really be able to concentrate.

HLB: Is there anything else you would like to share with us and the readers at this time?

JG: I’m grateful to the NYBG for its sponsorship, both of botanical illustration and plein-air art. While both may result in attractive images of flowers, the botanical artist is more concerned with portraying individual flowers with a scientist’s perspective, removing a plant from its context to understand form and function while still seeing the beauty in it. The plein-air artist pays attention to the whole living ensemble as influenced by light, air, atmosphere, spatial depth, and that intangible element of life and change. A goal of mine is to combine the two perspectives, to see both the forest and the trees.

To connect further with James Gurney, we invite you to visit his YouTube, Website, Instagram, or Facebook page.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.