Reading Recipes

Claire Bunschoten, Ph.D., is a Mellon Research Fellow at The New York Botanical Garden.

The New York Botanical Garden excels in celebrating plants, including those we eat. While vanilla permeates life in the United States from flavoring lattes to scoops of ice cream and scenting our bodies and homes, we do not always remember that vanilla comes from an orchid (Vanilla planifolia).

Vanilla has many homes at the New York Botanical Garden. The Lowland Rain Forest house of the NYBG’s Enid A. Haupt Conservatory tends to the living specimen and recently featured the vanilla orchid as part of the 2023 Orchid Show. The Steere Herbarium holds many preserved specimens from around the world to the benefit of a global research community of historians and scientists. The LuEsther T. Mertz Library, too, has access to many essential botanical reference texts which elucidate vanilla’s rich past, from its indigenous uses in Mexico to its trans-imperial global history and relation to plantation slavery as well as its imperiled future.

However, vanilla may be found, too, in the library’s substantive collection of cookbooks bolstered by the donation of William R. Buck, Curator Emeritus, Institute of Systematic Botany. Dr. Buck studied the relationships between different groups of moss and on his research trips around the world, he collected botanical books for the LuEsther T. Mertz Library and plant-oriented cookbooks for his own personal collection.

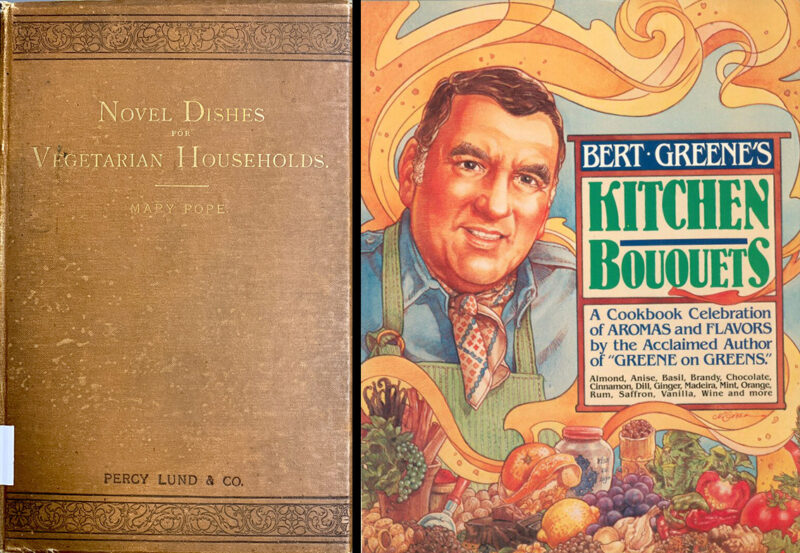

In 2019, Dr. Buck donated his cookbook collection to the library, and following a rigorous processing period, thousands of cookbooks from Mary Pope’s 1893 Novel dishes for vegetarian households: a complete and trustworthy guide to vegetarian cookery to Bert Greene’s discussion of his favorite culinary aromatics in Kitchen Bouquets (1986) are available to the public.

As a food scholar, cookbooks are vital research texts. These books may illuminate the status of a recipe or ingredients in a specific cultural or historical moment. Cookbooks also tell us a lot about aspirations, for although cookbooks communicate recipes we cannot know how people actually cooked from them but perhaps what they desired to cook. However, one of my favorite ways to approach cookbooks is through their introductions.

Scholars like Sarah Walden and Carrie Helms Tippen both suggest that introductions are where cookbook authors make clear ideological statements. While these sections in historical cookbooks may only be a paragraph or two, today they can span pages. While the content of these introductions can vary, from including instructions about measurements and ingredient selection to the author’s family history, they almost always make an argument for why the author has written the book. In this way, we can understand cookbooks as a form of argumentation that also acts as an invitation into the author’s worldview.

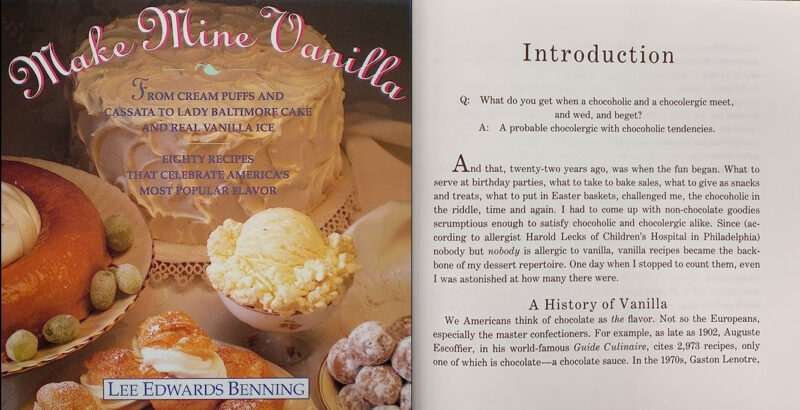

For an author like Lee Edwards Benning, the motivation for writing Make Mine Vanilla (1992) stems from family tastes: one chocolate lover surrounded by chocolate haters finds vanilla as the culinary middle ground. In the 28 pages that compose the introduction to the book, Benning shares vanilla’s complex history, explanations of the different vanilla products on the market (noting, “I do not recommend imitation vanilla.”), and explains the overarching rationale for the book’s assembled recipes: “when I cook, I want either something that goes together fast and tastes better than anything I could buy, or something so spectacular or family-pleasing that I don’t mind spending the time.” From all this, we can glean Benning’s deep respect for this ingredient, fondness for the botanical over the imitation, and a culinary sensibility that considers both the spending of time and money in the kitchen in relative to the outcome; in other words, Benning’s book invites its readers to cook alongside with these principles in mind.

In my own research, the choice between botanically-derived vanilla products like vanilla beans or extracts and imitation or synthetic vanilla is especially interesting, as it speaks to a larger conversation in the U.S. around the construction of what is considered “natural” as well as issues of cost. By and large, vanilla beans and pure vanilla extracts dominate the pages of the vanilla cookbooks in the Mertz’s collections.

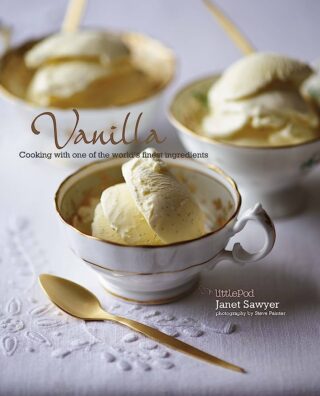

Should this surprise us? In one sense, not really. Vanilla beans and vanilla extracts make for wonderfully flavored food. Yet, I think there is also some space for skepticism here. For example, some of the cookbook authors like Janet Sawyer write their cookbooks in the interest of their own vanilla bean and extract businesses. Are their recipes still good? Sure! But is there a business interest at play in their texts? Absolutely.

Should this surprise us? In one sense, not really. Vanilla beans and vanilla extracts make for wonderfully flavored food. Yet, I think there is also some space for skepticism here. For example, some of the cookbook authors like Janet Sawyer write their cookbooks in the interest of their own vanilla bean and extract businesses. Are their recipes still good? Sure! But is there a business interest at play in their texts? Absolutely.

Taken together, these books offer a diverse and delicious point of entry into the complex world of vanilla. And, as a whole, the Mertz Library’s cookbook collection is a great resource for researchers of all levels—what better way to understand the plant world than to taste it? I hope you’ll check out a cookbook or two on your next visit.

If you would like to learn more about cookbooks as sources and subjects of literary and historical analysis, I recommend the following works:

Elias, Megan J. Food on the Page: Cookbooks and American Culture. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

Fisher, Carol. The American Cookbook: A History. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland, 2006.

Leonardi, Susan J. “Recipes for Reading: Summer Pasta, Lobster à La Riseholme, and Key Lime Pie.” PMLA 104, no. 3 (1989): 340–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/462443.

Theophano, Janet. Eat My Words: Reading Women’s Lives through the Cookbooks They Wrote. New York, N.Y: Palgrave, 2002.

Tippen, Carrie Helms. “The Literary Cookbook.” Billet. The Recipes Project (blog), September 27, 2016. https://recipes.hypotheses.org/8335.

Tipton-Martin, Toni. The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. First edition. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015.

Walden, Sarah. Tasteful Domesticity: Women’s Rhetoric & the American Cookbook 1790-1940. Pittsburgh, Pa. : University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018.

Worth, Susannah. Digesting Recipes: The Art of Culinary Notation. Zero Books, 2015.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.