Recapping ‘First Nations: Ethical Landscapes, Sacred Plants’

Speculative Algae (detail), watercolor by Zoe Todd

On November 13, 2020, the virtual symposium First Nations: Ethical Landscapes, Sacred Plants drew more than 550 participants from across the nation and 23 different countries. This unique symposium brought together Indigenous environmental experts from America and Canada to discuss the medicinal and nutritional value of plants, as well as models for ethical and sustainable use of land threatened by industrial pollution and climate change. Marking the Humanities Institute’s Eighth Annual Symposium, this lively event was convened in partnership with Yale University and its project The Order of Multitudes: Atlas, Encyclopedia, Museum, a year-long series of events sponsored by the Mellon Foundation.

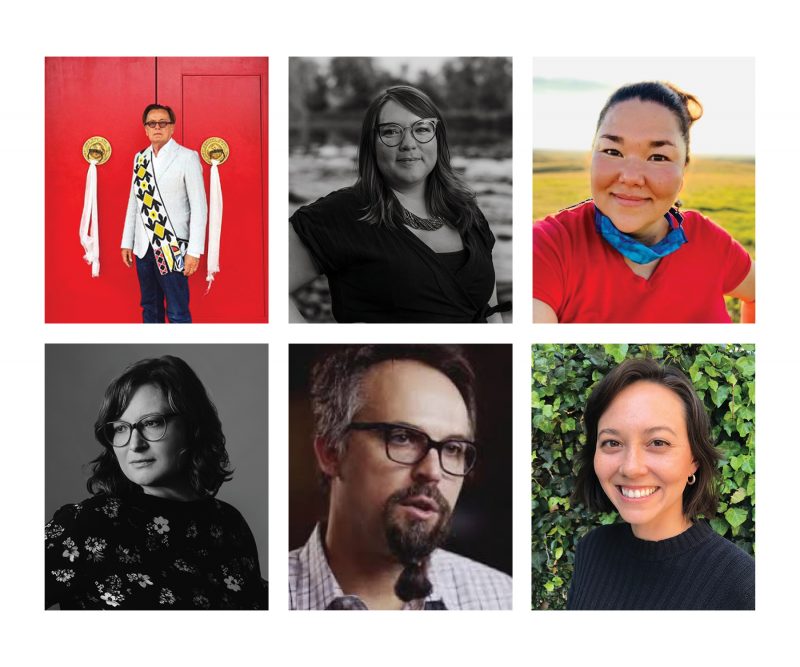

Symposium Speakers and Moderators, top left to bottom right: Joe Baker,

Zoe Todd, Linda Black Elk, Janelle Baker, Kyle Whyte, and Ashanti Shih.

Joe Baker, Executive Director of the Lenape Center in New York, set the tone, welcoming all to Lenapehoking with a personal prayer in the Lenape language. His remarks followed a short introduction by Raquel Nazario, Chief Diversity Officer at NYBG, who welcomed the audience on behalf of the Garden’s Humanities Institute, its Director Vanessa Sellers, and co-host Deborah Coen, Chair of the History of Science & Medicine Program, Yale University.

Moderator Zoe Todd (Métis), Associate Professor of anthropology at Carlton University, Canada, first introduced Linda Black Elk (Catawba Nation) for her presentation, “Plants Are Our Relatives.” The well-known ethnobotanist and food sovereignty coordinator at United Tribes Technical College, Bismarck, North Dakota stressed the age-old significance of building a deep personal connection and understanding of plant life, pointing out important food sources on the Great Plains today, such as Pediomelum esculentum, called Thíŋpsiŋla [timpsila] in Lakota language.

Linda Black Elk’s sand cherry pie

One of Linda’s fascinating stories focused on the Sand Cherry (Prunus pumila; Aunyeyapi in Lakota). “So the sand cherry is actually a really amazing plant. When I was growing up and learning about plants, I was told by so many of my teachers that you have to approach the Sand Cherries from downwind [to make sure the berries are sweet for a pie]. Otherwise they’ll smell you coming and they’ll turn bitter.” Initially thinking this story was a metaphor, Linda tested the plant in the university lab and discovered there are actually stomata on Sand Cherry stems that open and close and take in pheromones of approaching animals. In response, they produce bitter alkaloids that prevent predators from eating too many—how about that!

Following Linda Black Elk, Janelle Baker, Professor of Anthropology, Athabasca University, Alberta, Canada, presented “Who are you Calling ‘Common’? Cultural Keystone Species in Extractive Zones.” This introduced the audience to the largely overlooked boreal forests in northern Alberta tended by Northern Bush Crees, who follow ancient reciprocal ethnobotanical traditions.

Mountain ash as discussed by Janelle Baker

Ironically, one of biggest problems the Bush Crees face in dealing with government and corporations is that many of their sacred, cultural keystone plants—Willow Tree, Mountain Ash, Paper Birch, and especially the Balsam Poplar—aren’t rare but are actually common species. “This makes it really difficult to convince a company that those patches of Mountain Ash and Willow need to be protected,” explained Janelle. This serious misconception may affect the wide use of these plants for medicinal and spiritual purposes by next generations.

Kyle Whyte’s presentation opening slide

Kyle Whyte (Citizen Potawatomi Nation), Professor of Environment and Sustainability and George Willis Pack Professor at the University of Michigan, continued the conversation in “Questions of Ethics and Justice in Coalition Building.” Kyle outlined how botanical gardens, like other cultural institutions that have supported and profited from colonialism, can now learn to build true “kinship alliances.” This means working with Indigenous scholars on equal footing and with due humility toward more sustainable relationships with plants and people, assuring involvement of all parties from the point of conception. “Also,” Kyle added, “while common ground is important, and we know that a lot of members of privileged populations like to talk about establishing common ground, difference is important, too. Recognizing the technology and learning about difference is crucial.”

A lively panel discussion moderated by Zoe Todd offered important advice supporting food security and continuing advocacy work in Indigenous communities in a time of pandemic. The speakers also discussed how to best navigate scientific and government spaces that are still learning about the depth of Indigenous knowledge and self-determination.

Finally, Ashanti Shih, current postdoc at USC, Yale Ph.D., and former Mellon Fellow at NYBG’s Humanities Institute, moderated an audience Q&A. One key question centered on the apparent difference between Indigenous scholarly research, which aims to help community and general consensus, and Western research, which stresses individual accomplishment.

Compliments filled the chat box as the symposium came to a close. Co-host Deborah Coen spoke for many when she noted: “This event clearly meant a great deal to a lot of people—to Indigenous communities on multiple continents, and hopefully to leaders and patrons of many different botanical gardens, who will be inspired by your visions for coalition and kinship.”

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.