Revisiting Vanuatu’s Calendar Plants

Ysabel Bote is a Science Intern at the New York Botanical Garden.

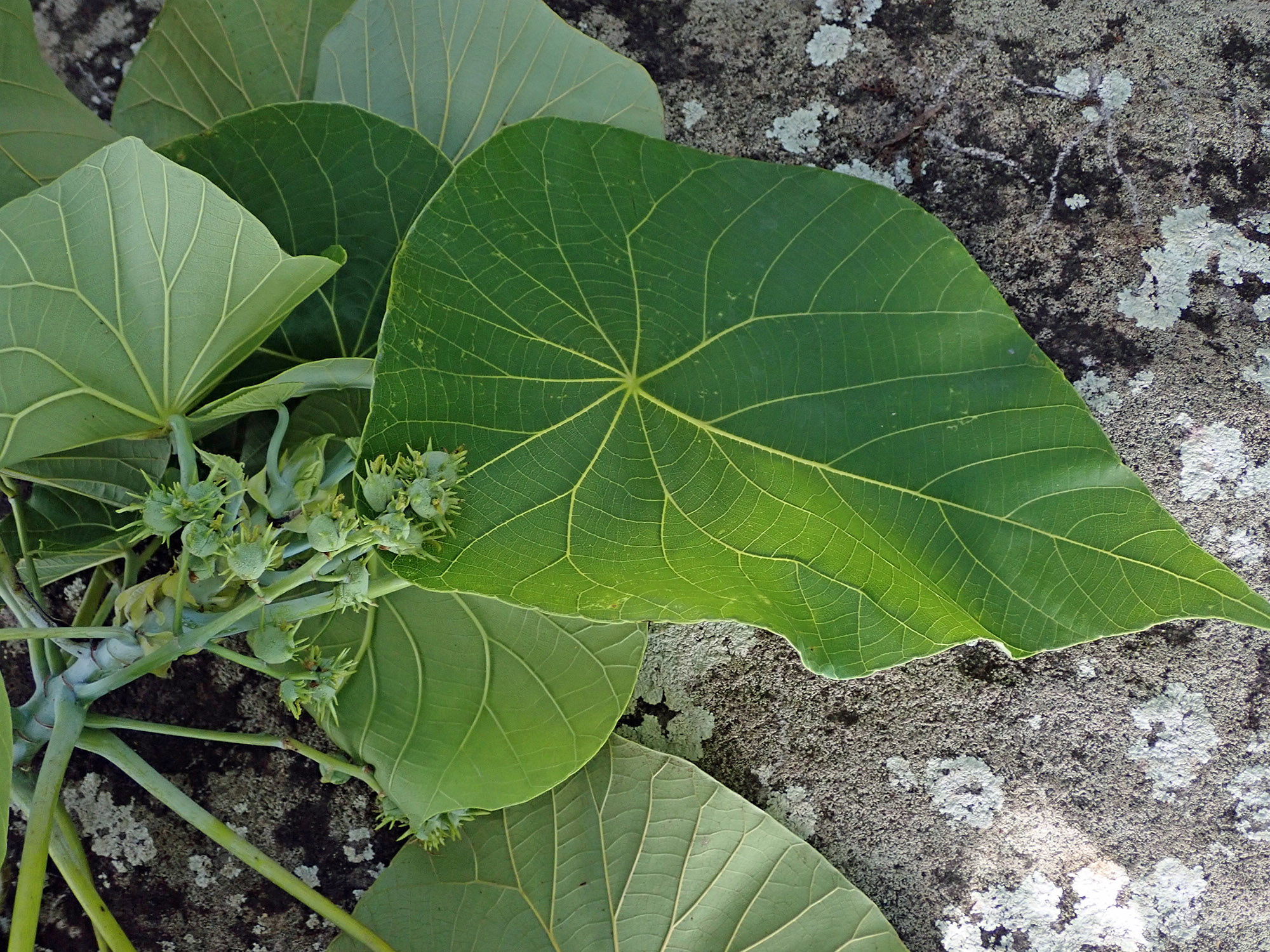

Gardenia tannaensis in bloom signals its time to harvest taro root.

This morning, you probably woke up to the blaring sound of your alarm alerting you it’s time to wake up. You acknowledged all the bright red octagonal signs driving around a roundabout so you knew to stop and be mindful of your surroundings. During October, you begin to cross paths with crunchy orange leaves, encouraging you to prepare for colder seasons. These are signals we apply daily, some of which occur all year long or alternate based on different months. These cues work similarly to the ones locals use on the islands of Vanuatu, an archipelago in the Pacific. These cues are calendar plants, which are used to interpret the environment and inform human activities throughout the year.

Vanuatu has 83 islands and its people speak over 30 indigenous languages. Some of these languages are Nate and Netwar (both spoken on the island of Tanna), and Anejom (spoken on the island of Aneityum). Despite linguistic diversity, locals are naturally brought together by one thing: food. From the harvest of taro to hunting flying foxes, islanders share a common knowledge of calendar plants to be alerted when these plants and animals are good to obtain. Calendar plants grow, bud, fruit, or attract local fauna at certain times of the year, telling islanders it’s a good time to hunt animals, harvest crops, or start a new garden.

Taro (Colocasia esculenta) is a prominent crop in Vanuatu. In Tanna (Netwar-speaking regions), when a plant known as neroa (Gardenia tannaensis) is in bloom, it indicates it’s time to start harvesting taro.

A single plant is also capable of offering multiple cues, providing information about many foods. For instance, when naketip (Barringtonia racemosa), located in Tanna, begins to bloom, locals know that puskats (feral cats that typically live in bushes), are plump and ready to be captured. Additionally, when naketip produces fruit, it tells locals it’s a good time to start planting yams.

In Aneityum (in regions that speak Anejom), islanders observe plants grown on land to know when life in the ocean is ready to be hunted. An example of this is when naurakiti or billygoat weed (Ageratum conyzoides) is in bloom, locals know that sea turtles are plump and ready to be hunted. When the flowers of nihivaeñ pap (Macaranga tanarius)—a short bushy tree distributed in tropical areas—begin to appear, islanders know that eels have a lot of fat, a perfect time to hunt them.

In June, fruits of nouh merek trees (Grewia prunifolia) begin to ripen. These trees and their fruits act as calendar plants because they thrive exclusively during the cooler season, and they attract flying foxes, a species of megabat that is endemic to Vanuatu. Hunters strategically surround this tree to stalk the flying foxes. Similarly, hunters would strategically surround Ficus obliqua (a tree known by various names in Nate-speaking regions of Tana) to hunt birds attracted to its fruits.

For many generations, calendar plants have remained fundamental parts of Vanuatu and Pacific Island culture. By listening to the natural world this way, local calendar plants are not just pillars of environmental sustainability in Vanuatu, but in social and cultural sustainability as well.

For more information on Vanuatu’s calendar plants, see our previous update from Drs. Mike Balick and Greg Plunkett.

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.