Urban Forests: Good for the City and for the Climate

In our first post about Brad Oberle, an associate curator in the science division at NYBG, he introduced himself as a “tree hugger”—and it’s true, both figuratively and literally. Oberle is passionate about protecting the environment—and the way he does it is with hands-on research that does indeed involve hugging trees (with the help of a measuring tape) to get data like their circumference or density, which will in turn provide significant information such as carbon content or age. At NYBG, Oberle is determined to study forest ecology in order to understand their effects on climate and community.

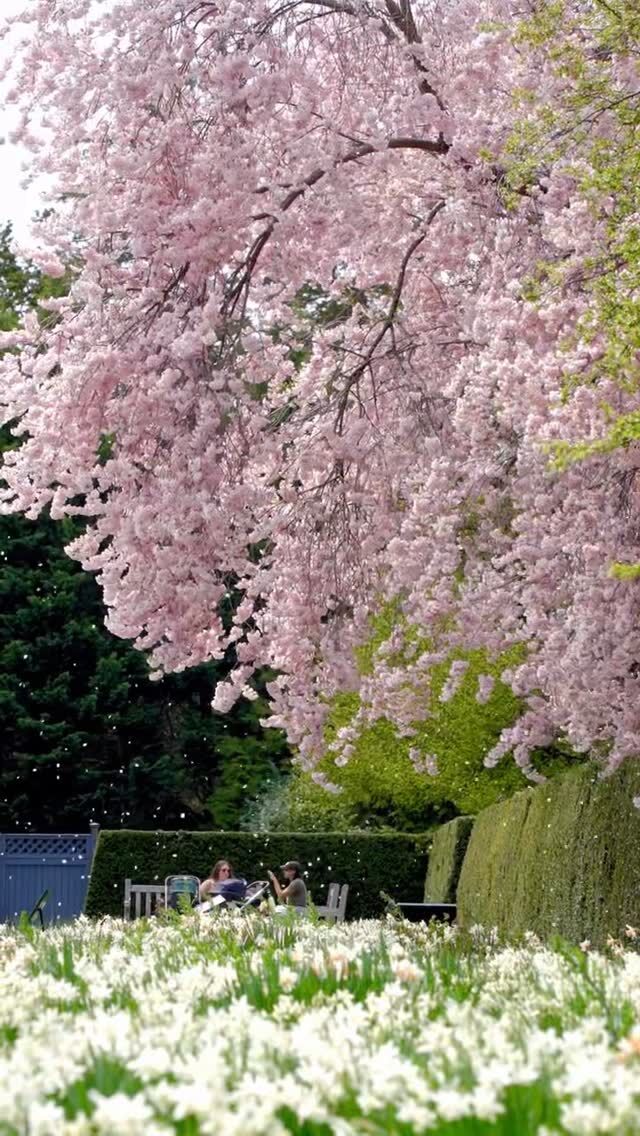

The Thain Family Forest is a peaceful oasis full of rich biodiversity. Now, in late October, it is especially magical—the crimson hues from the maple, the pale yellow of the beech trees, and the cream-colored coral mushrooms all add to its spectacular tapestry of life. But beyond its beauty, it also serves as a crucial green space that provides benefits for communities of all kinds—plants, humans, and other animals.

As an old-growth forest, it has developed over a long period of time, escaping catastrophic disturbances so that layers of trees and vegetation can thrive. For research purposes, it allows us to gauge how the landscape has changed throughout its existence due to environmental changes—such as glaciers, vernal pools, the Bronx River, hurricanes, and other natural phenomena—and human footprints—indigenous inhabitants of the Forest like the Lenni Lenape people, early European settlers, and now, the impacts of modern society and a changing climate. The Thain Family Forest, full of native flora, also provides a way to track how those plants have adapted over time, given environmental shifts and the onslaught of invasive species.

“We live in one of the greatest cities on the planet,” Oberle said. “And here on the grounds in the New York Botanical Garden, we have one of the greatest urban forests in any city anywhere.”

Just like a forest’s network of roots, environmental scientists’ network and collaboration are key in understanding how forests can benefit an urban community and have resounding effects across the globe. For example, NYBG is part of The Nature Conservancy’s “Forest for All New York City” coalition, which hopes to create a shared plan for an urban forest whose benefits are equitably distributed to all residents of New York City.

What are these benefits? While forests are complex, we can condense their ecosystem services, for urban areas in particular, to three points:

1. Forests help a space stay cool.

“It can be on the order of 5 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit cooler under a canopy or in the vicinity of an urban forest than it is in a lawn or especially on a street or in a parking lot,” said Oberle. “So as temperatures get hotter and our infrastructure becomes more strained, those services provided by forests—specifically the cooling impacts of forests—are really vital for our health.”

The most obvious way trees do this is through shade: forests absorb large amounts of sunlight. However, trees also provide cooling through evapotranspiration: a combination of evaporation—when liquid becomes vapor—and transpiration—the process by which trees absorb water through roots and release it as vapor through their leaves. Oberle compared this to measuring the heartbeat of trees.

“Every day they shrink and swell as water moves through them and they do photosynthesis,” said Oberle. “As water moves through, it evaporates—and just like our sweat evaporates and cools us, water evaporating from tree canopies cools the canopies and their surroundings.”

2. Forests are carbon sinks, meaning they sequester carbon from the atmosphere.

Get ready for a quick science lesson! Remember photosynthesis? Here’s why it’s important—for trees, and for us.

In order to photosynthesize, trees pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and through chemical reactions, release oxygen and make glucose. The latter contains carbon and is deposited in biomass like trunks, branches, roots, and leaves. Carbon in trunk wood stays with trees for their entire lifespan, and only returns to the Earth’s natural carbon cycle through decomposition—when decaying matter like leaf litter or rotten wood are broken down by decomposers, such as fungi.

“[That’s] the big picture in terms of how the carbon cycle works, when you’re not just talking about one carbon dioxide molecule in one plant,” said Oberle. “Instead, you’re talking about all the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and all the landscapes on the planet—how they operate over decades and centuries.”

Trees are therefore carbon sinks: they absorb more carbon than they emit—one study found that the world’s forests sequester about twice as much carbon dioxide as they release. We can see the impact of forests just within our city: forested natural areas make up a quarter of the total tree canopy in New York City, but account for 69% of the carbon stored and 83% of carbon sequestered by trees across the city, according to the Natural Areas Conservancy.

“Since 1850, when the Industrial Revolution really kicked off, about a quarter of all the carbon that we have put in the atmosphere has been absorbed by forests,” said Oberle.

In an increasingly warming world, mainly due to the carbon dioxide in our atmosphere, carbon sinks are critical now more than ever.

3. Forests are havens for biodiversity.

With shrinking habitat in urban areas, the uninterrupted land that forests provide is incredibly important for species.

“All the kinds of animals that depend on trees, microorganisms, interdependent trees, so many aspects of urban biodiversity, are concentrated in urban forests,” said Oberle.

On the broader scale, forests cover about 31% of the world, but contain more than 80% of all terrestrial species of animals, plants, and insects, according to the U.N.

So we know why a woodland like the Thain Family Forest is so important to an urban area. But how does our special 50-acre woodland connect to other urban forests? Well, that’s exactly what Oberle’s trying to figure out.

“There’s a real opportunity to use the Thain Family Forest as a globally significant reference for urban forests,” said Oberle. “A city is a city in many ways…urban ecology is something that we’ve learned, is a discipline, has consistent themes, and it doesn’t matter whether you’re in the subtropics, like in Florida; the temperate zone, like we are here; or any other city around the planet—you still have an urban heat island. You still have certain changes to the soil.”

But even beyond urban areas, what happens in forests, urban or not—and in any ecosystem for that matter—impacts the global environment. Everything is connected. Oberle has worked with various plant species and biomes, including a very different kind of forest: mangroves. In a future post within this series, we’ll be diving into these salty, coastal ecosystems.

“What happens in a mangrove in Florida has ramifications for the sea level rise, the intense storms, and the increasing heat that we’re experiencing here in New York City,” said Oberle. “Even things that seem as exotic and far away as mangrove biology connect to the challenges we face here in New York City, because those challenges are global.”

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.