Vanuatu Celebrates its 40th Year of Independence and Learns a Lot about Botany

Gregory M. Plunkett, Ph.D., is Director and Curator of the Cullman Program in Molecular Systematics at The New York Botanical Garden.

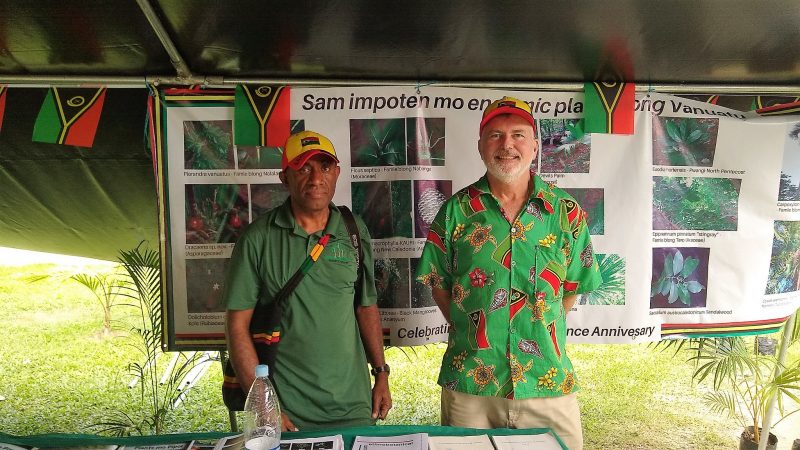

Presley Dovo, head of the Vanuatu Department of Forestry’s Botany and Conservation Unit, with Gregory M. Plunkett, Ph.D.

Vanuatu, a South Pacific archipelago of about 85 islands, celebrated the 40th anniversary of its independence recently with a 10-day public holiday, including an Agriculture Festival that provided a truly wonderful opportunity to present an exhibit showcasing the important work of the Vanuatu National Herbarium. I was honored to help create the exhibit, which featured NYBG’s collaborative project Plants and People of Vanuatu.

I coordinate this project along with Michael J. Balick, Ph.D., NYBG’s Vice President for Botanical Science and Director and Philecology Curator of the Institute of Economic Botany. We work with partners from the Vanuatu Department of Forestry (DoF), the Vanuatu Cultural Centre, and an international team of colleagues from several universities. I arrived in Vanuatu in mid-March for a brief, two-week stay, but then international borders closed suddenly because of the COVID-19 pandemic, stranding me here. Because the disease never reached this country, however, I have been able to continue research on the project.

Vanuatu achieved its independence on July 30, 1980, after nearly a century of co-rule by the British and French that came to be known as the “New Hebrides Condominium.” Despite its young age as an independent nation, Vanuatu has a long history, beginning with its settlement by the native Melanesian people around 5,000 years ago.

Presley Dovo discusses the Vanuatu National Herbarium exhibit with Agriculture Festival attendees.

As part of the festivities commemorating the country’s independence, the Vanuatu Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Forestry, Fisheries and Biosecurity hosted a three-day Agriculture Festival in which each department of the ministry organized displays and exhibits, styled as “villages.” In the Forestry Village, Presley Dovo, head of the DoF’s Botany and Conservation Unit, took the initiative to create an exhibit that explained the purpose and role of the Vanuatu National Herbarium, along with explanations of what herbarium specimens are and how they are made, the history of botanical exploration in Vanuatu, Vanuatu’s native and endemic flora, and past and current botanical projects in the country.

I worked closely with Presley and two DoF interns, James Ure and Kevin Kausei, to assemble an extensive exhibit. It included displays that detailed the history of botanical exploration in Vanuatu, starting with Johann and Georg Forster, two botanists who sailed with Capt. James Cook on his second voyage to the Pacific, during which they collected the first scientific herbarium specimens from the archipelago in 1774. The displays proceeded through the 19th and 20th centuries up to the present, showcasing the Plants and People project that commenced in 2014, including a video about the project and demonstrations of the series of Online Talking Dictionaries spearheaded by a project collaborator, Professor David Harrison, a linguist at Swarthmore College in Philadelphia. The exhibit also showcased many of Vanuatu’s native and endemic plants on banners hung behind the display tables.

Exhibit organizers and attendees with the flag of Vanuatu

Roughly 20,000 people attended the Agriculture Festival, and at least half passed by the Vanuatu Herbarium exhibit. Presley, James, Kevin, and I provided detailed interpretive explanations of the outdoor exhibit to at least 1,000 people, many of whom also took tours of the herbarium. Among these were the directors and staff of other government departments, directors general of national ministries, current and past members of parliament, current and former government executives (including several former prime ministers), civic leaders, prominent members of the expatriate community, and other national and local leaders, as well as many members of the general public, including many teachers and family groups.

With no COVID-19 cases on the islands of Vanuatu, roughly 20,000 people were able to safely attend the Agriculture Festival.

Most of these visitors expressed amazement at what the team was doing and surprise that this kind of research was being conducted. In general, they said they thought that the Forestry Department was merely focused on chopping down timber trees, not saving Vanuatu’s plant life. There was universal agreement that this kind of research is critically important, especially since species are being lost to increased land exploitation and because traditional knowledge about how plants are used is disappearing, as are the names of these plants in the many indigenous languages of Vanuatu, of which there are at least 112 (making Vanuatu the most language-dense country in the world per capita).

Compared to the problems caused by COVID-19 across the globe, the inconvenience of my temporary exile is quite mild, but I have sought to use this extra time in Vanuatu (now amounting to nearly six months) to keep active, working closely with my Vanuatu colleagues to raise the awareness and profile of our important research here. As the people of Vanuatu celebrate the 40th anniversary of their multi-ethnic, multi-cultural, and multi-linguistic nation, it seems that this country, one of the world’s smallest and newest, might have something to teach the rest of the world, if only other countries might look and listen. Happy 40th Birthday, Vanuatu!

SUBSCRIBE

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive updates on new posts.